US and the British royals: The fascination explained

- Published

Jane Giannoulas from San Diego waiting outside Buckingham Palace after the wedding of Prince William

A special exhibition of British royal portraiture has come to Texas from London, just as a Netflix show documenting the life of Elizabeth II, The Crown, sweeps the Emmys. How has the US fascination with the royals endured?

With an elegant white fur collar around her neck and beneath the sparkling diamond diadem from her 1953 coronation the Queen's eyes are beguilingly closed - is she asleep, thinking about what cocktail to have before supper, or contemplating death?

Chris Levine's intimate and enigmatic holographic portrait of Queen Elizabeth II is one of 150 objects - most never seen before outside the UK - now telling an audience in Houston the story of Britain's monarchy across five centuries through masterworks of painting, sculpture and photography.

"The image came from a sitting Chris Levine did with the Queen during which she rested between photographs," says Louise Stewart, a curator with London's National Portrait Gallery (NPG) that is partnering with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), and which never before has allowed such a large number of its masterpieces to travel.

"She's dressed so royally but her closed eyes create a sense of vulnerability. It makes you realise that despite her being so recognisable, the most photographed person in history, we still hardly know her and rarely get beyond the surface - it's very haunting."

The MFAH is the only US venue hosting Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits from Holbein to Warhol.

Interest in the British monarchy certainly spans the globe, but in the US it occupies a special place, spurred in recent years by the impact of media productions and real-life events.

These range from successful TV shows such as The Crown - just awarded two Emmys - to this year's marriage of American actress Meghan Markle to Prince Harry.

When Prince Harry wed Meghan Markle at Windsor, it was huge news in the US

News of Meghan Markle's pregnancy made headlines in the US. But even the minor royals don't go unnoticed - the wedding of Princess Eugenie on Friday was greeted by a few shrugs and a "Who?" but it was the most viewed story in North America on the BBC News website.

The stateside exhibition is further evidence, if any more is needed, of the intriguing relationship Americans have with the British monarchy, in which despite their country being built on rebellion against the British crown, Americans appear unable to get enough of their former rulers.

"The status Britain's monarchy has in US popular culture is extreme and a 20th Century phenomenon," says James Vaughn, assistant director of British Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Mr Vaughn recalls going to Yale in 2011 for research and renting a room in a home where the whole household woke up at 5am to watch the wedding of Prince William.

"In the 18th and 19th Centuries the monarchy was viewed as the chief of the Old World, a redoubt of privilege and hereditary status, at odds with the new Republic's freedom. [But] the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was a huge event in the US, and the phenomenon has continued from there."

Since World War Two there has been a decline in trust of the American elite and governmental system, Mr Vaughn says.

"JFKs assassination, Watergate, the Iran-Contra affair, those all eroded public faith, and it's now at its lowest level. So the fact Britain has this distinction between the head of government and a hereditary, non-powerful head of state who can't be sullied in the same way as the head of government by dirty politics - many Americans like that."

Rabbi Howard Berman is an avid royal enthusiast from Boston

At the same time, Mr Vaughn notes, Americans can't get enough of the royal scandals gracing covers of the ubiquitous tabloid magazines beside checkouts in grocery stores throughout the country. But they nevertheless tend to forgive such episodes, he says, viewing the British monarch like a beloved Hollywood celebrity.

"Also, the US is a continually changing society, in which celebrity comes and goes, but with the British monarchy it is a guaranteed celebrity, as everything passes on to the children."

This monarchist legacy was on the mind of British photographer Jason Bell when he took the christening photos of Prince George, one of which features in the exhibition.

As a Brit based in New York, Mr Bell has directly experienced the US take on the British monarchy. "There is such affection for [them] in America," he says. "I hadn't anticipated quite the depth of emotion they invoke. That has been very nice to witness."

Such a positive view has probably been encouraged by shows such as The Crown presenting the monarchy in a relatively positive light.

"Before the show, many Americans didn't know the how [Queen Elizabeth's] uncle had abdicated, and then her father died, forcing her to become queen," Mr Vaughn says.

Olivia Colman plays the lead in latest series of The Crown

Similarly, the monarchy as a historical institution represents a more stable bygone era for Americans perplexed by or fearful of the current climate.

The exhibit touches on two key events highlighting this interplay between history and how the British monarch is perceived.

"In the 1830s the advent of photography meant you suddenly had these pictures of Victoria and Albert relaxing with family," says the MFAH's David Bomford.

"It was an astonishing transformation, as you could now see their expressions, moods and interactions, which before artists could edit out."

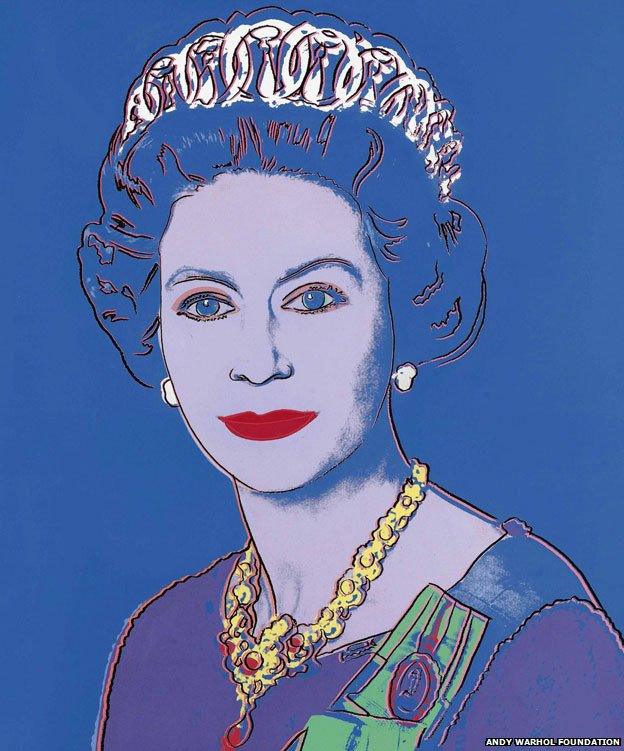

Then in the 1980s, the American artist Andy Warhol unleashed his pop-art screenprint of the Queen, signalling the British monarchy's appropriation by popular media.

"He made the queen into a consumer icon," Ms Stewart says. "The image doesn't say anything about the queen, it's all just at the surface level, making her a product that can be endlessly reproduced and consumed."

Nevertheless, the somewhat counter-intuitive fact remains that despite American culture perhaps doing the most to commoditise the British monarchy, to many Americans it means a whole lot more.

"The Queen has a grandmotherly quality, which helps her to be a figure of national affection," says Mr Vaughn, who questions whether Charles will maintain such a high level of public sympathy.

It's all part of an ongoing process in which the monarchy's 500-year history is continually being reassessed, Mr Bomford notes.

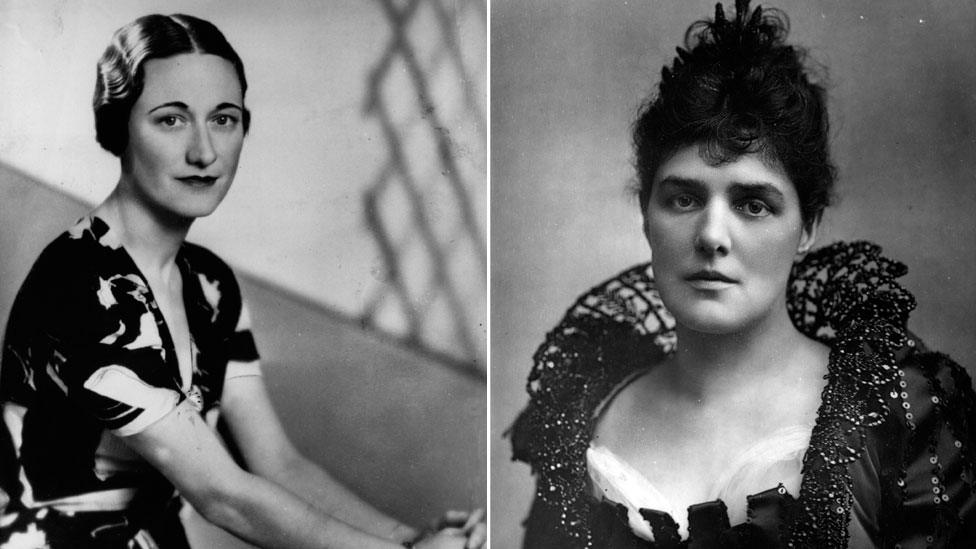

Witness recent events, he says, such as the discovery of the remains of Richard III buried beneath a Leicester car park spurring interest in the Plantagenet dynasty, and ongoing research into the abdication crisis, which is casting Wallis Simpson in a more sympathetic light.

Americans in British political history

Wallis Simpson, later Duchess of Windsor, and Jennie Churchill, mother of Winston

King Edward VIII abdicated for the woman he loved, Wallis Simpson, who was born in Baltimore

New York-born Jennie Jerome was only 19 when she met Randolph Churchill but they fell in love and got engaged three days later

The American divorcee for whom King Edward VIII abdicated isn't the only one benefiting from such royal reappraisals.

"Many Americans think the American Revolution was against King George III, as some sort of tyrant, but the revolution was against the English Parliament and the measures it was taking in the country," Mr Bomford says.

Even in the UK and in Commonwealth nations where the Queen remains head of state, the British monarchy remains a controversial institution.

The US is not exempt from such concerns, with some Americans criticising the monarchy as representing a Britain that is stuck in the past, elitist and class-ridden.

"There was and is anti-monarchical sentiment that is both political and class-based - historically, it was most pronounced among Irish immigrants, but then spread to socialists and many others," says Elisa Tamarkin, author of Anglophilia: Deference, Devotion, and Antebellum America.

On tour in Texas - King George III by Allan Ramsay and Queen Elizabeth II by Cecil Beaton

But Ms Tamarkin thinks these concerns appear less common today in the US and "that there are allowances for British royals - and a very striking and popular devotion to them - that would never be indulged toward our elite at home".

Ms Tamarkin is not alone in saying that a big part of the appeal of Royal Family, and the Queen in particular, is how it stands above the fray of party politics.

This has an enduring appeal in the US - with its lack of separation between the head of government and the head of state - where the president "acts more like an imperious king than any prime minister ever could".

"Royalty in Britain is there for display - and as Americans we can fall back into the pleasures of adoring the personalised charm of a prince or princess," Ms Tamarkin says.

"Monarchy puts a premium on all sorts of things that seemed to be lost in democratic life - feelings of awe, of reverence, of personalised attachment to authority; the desire to live in a world filled with worthiness and grace.

"Also, the fun of being naively enchanted."