The feeling that end-of-life carers won't admit to

- Published

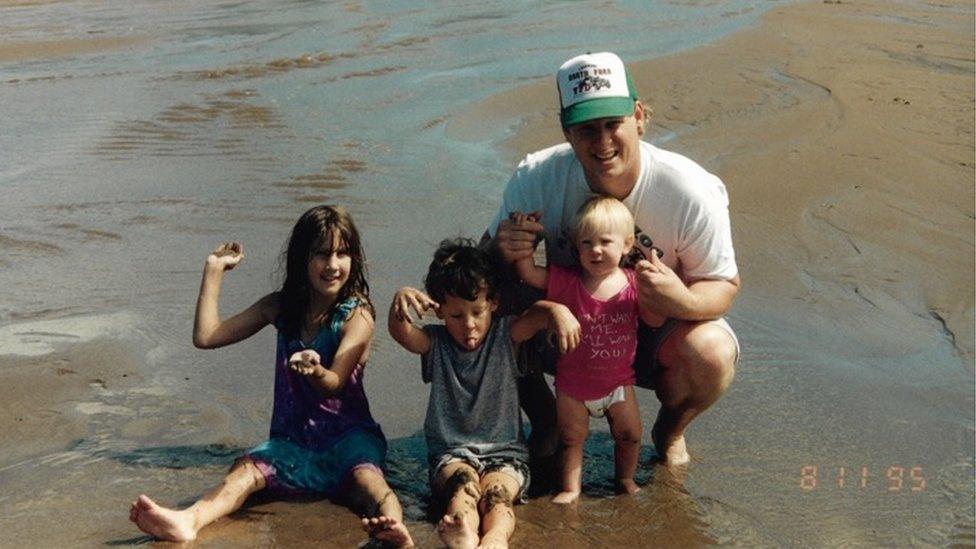

Kendall Fortner with his children Brittany, Terra and Christian

When Brittany Fortner speaks about her dad Kendall, her voice cracks.

Kendall, who died four weeks ago, was not yet an old man. At just 53, he made it abundantly clear he wasn't ready to go.

In life his strength and resilience made him a formidable, inspirational character. But in dying, his stubbornness was hard to navigate.

An incident in his final days left Brittany with feelings which many family carer-givers experience - but few admit to.

Her confession highlights the emotional complexities of caring for someone at the end of their life.

She's not alone. Looking after ill relatives is a task which many will face, as populations live to increasingly older ages.

More than 90 million Americans currently care for family with chronic conditions, while in Britain, informal care at home for people aged over 65 is predicted to increase by 87% by 2032., external

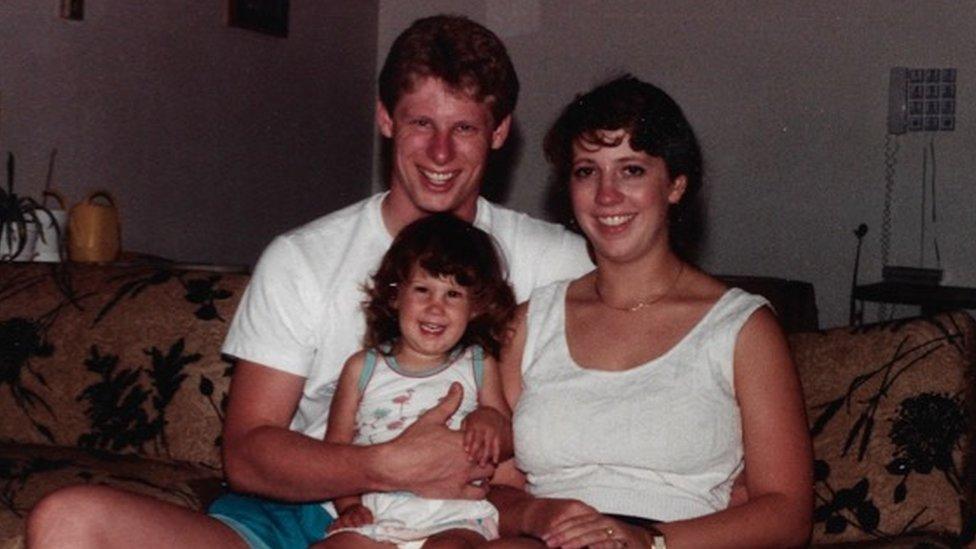

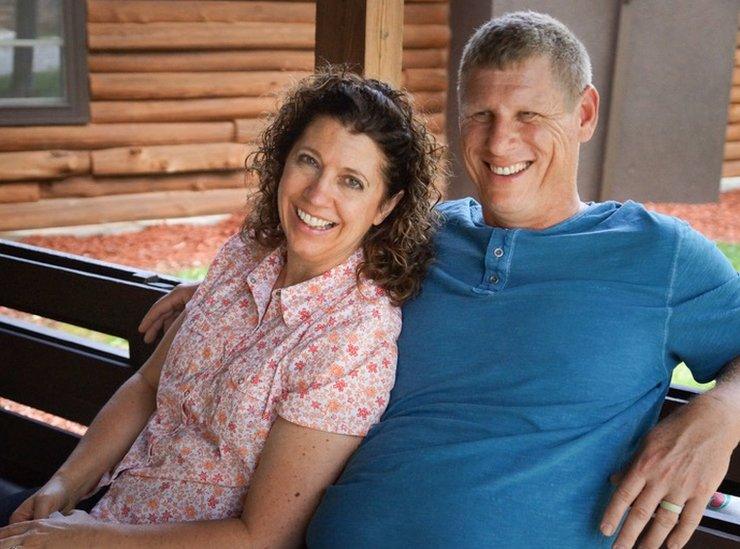

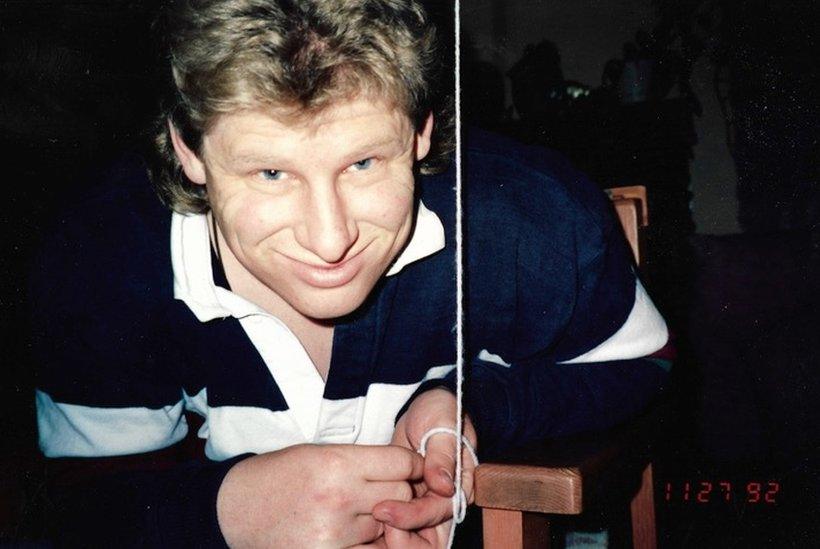

Kendall, 53, ran a property business in Springfield, Missouri where he lived with his wife Carol, 52

Kendall Fortner was first diagnosed with throat cancer two and a half years ago. He received treatment but after two remissions, the family knew it was terminal in October 2017.

"I would describe him as a visionary. He really made a difference. We did everything together - he was a wonderful father and we were all really close to him," Brittany, 32, explained shortly after her dad died.

In September she spent 10 days in the family home where Brittany's mum Carol, a nurse, was caring for him, along with Brittany's siblings Terra and Christian.

By then Kendall was so weak that he couldn't stand, and Brittany sat with her dad, sometimes chatting to him, but mostly just spending time together.

Left to right: Kendall, Carol, Terra, Brittany and Christian

"When I arrived, he could still recognise me. He wanted to hold my hands, which we did for several hours, while he drifted in and out.

"At some point he said he wanted to sit 'presidential style' in his chair. He gathered us together to tell us how much he loved us and how proud he was. He gave us all a hug. He was so ill that this took 10 minutes."

Kendall's sleeping was erratic and, still awake one early morning, Brittany asked him to take his morphine so they could sleep.

"I looked him in the eye and told him I loved him, and he said it back to me. I didn't know it, but that was the last time he was aware enough to know who I was. He became comatose and we thought that was it."

Two days later Kendall woke up. That's when the confusion started.

Brittany Fortner, 32, works in medical finance in Arizona

"He started talking like he hadn't in months - he hadn't been very chatty because of the tumour," Brittany explains.

Kendall couldn't recognise his surroundings. "He said we had to get him out of there. He wanted to go outside and tried to get out of the chair, which was very dangerous."

Trying to calm him down, Kendall's family found his shoes and put them next to him.

Kendall had been prescribed very strong painkillers to manage the throbbing pain from his tumours, and not eating was causing serious bone and muscle ache. But the medication, coupled with his body beginning to shut down, was making him delirious and confused.

Character changes, delirium, confusion and agitation are normal, external, but usually extremely difficult for family members to manage, as highlighted in a recent Reddit post about families, external losing patience or lashing out at relatives.

These periods of "great confusion", when he seemed nonsensical, scared Brittany. But as well as alarm, her feeling of frustration - even irritation - became palpable.

"As his child, it was so hard to see this man who had been so intelligent that you could ask him anything, starting to babble.

"I depended on him for advice. When I was a grown adult, I even had to tell him to stop buying my car insurance. He just wanted to take care of us.

"To switch from that to him being so dependent, was truly heartbreaking.

"Suddenly he said, 'I figured it out. I'm not mentally with it'," Brittany says.

Kendall refused to take any more painkillers. "We kept trying to offer him medicine. He would firmly say no and clamp his mouth shut."

This began a cat and mouse game of balancing Kendall's deteriorating health with his wishes to remain mentally present.

Kendall lived with his wife Carol in Springfield, Missouri

This reaction is common, especially in younger patients who feel medication is something they can influence in the face of losing so much control of their lives, explains Jane Kaschak, a nurse at Valley Hospice in Ohio.

"One of the hardest things for a family care-giver is deciding when the benefits of medication are worth the burden on the patient. It's a fine line to walk," she says.

She advises care-givers to think about how they want their own death to be, adding that hospice care in America can help people struggling with end-of-life care.

When the morphine lost its effect, Kendall's clarity of mind returned. Brittany's mum Carol could do things like reading aloud to him, a tradition the couple had performed for decades.

"As a nurse, I feel strongly about the individual's right to self-determination, but I knew he was in pain despite his denial," Carol explained.

Kendall spent the following day sleeping in fits and starts, as the family tried to manage his wishes and symptoms.

Not normally a man with a quick temper, Kendall became enraged when he was too weak to drink from a glass, and instead needed liquid squirted into his mouth with a plastic syringe.

"His anger was shocking to see. He said we were babying him but he was so weak," Brittany explained.

The family didn't agree about what they should do. Brittany's mum wanted to keep administering medicine, but Brittany's brother thought he had had too much.

"We didn't want to force him, but we would see him coming down from a bit of a high, and to see his frustration and anxiety during those moments was horrible," says Brittany.

"As much as possible, I would respect his wishes. However, as his cognitive ability declined, his quality of life took precedence over his wishes," Carol explains.

"I felt bad for praying he would just go to sleep in the middle of the night when he was so combative and I was so exhausted."

"It's a moral line," adds Brittany. "We knew his wishes were not to have it but he was in such bad shape when he didn't take it.

"We just had to try to support him without making him angry at us."

Kendall Fortner died on 27 September 2018 aged 53

In the end the family reached a compromise. If Kendall was alert and refused medicine, they didn't force him to take it. But when he was asleep, they administered the painkillers.

Brittany eventually had to return home to Arizona for work, and spent their final night together observing and sitting with her dad. "I had real feelings of frustration and guilt about how to care for him in those last days," she says.

When Kendall died two days later, Carol said the most difficult emotional response was guilt, particularly as he "fought so hard to hold on to life".

"I felt guilty for medicating him such that I knew I had sedated him, but I knew it was in his best interest."

For Brittany, the experience made her realise that she wants her loved ones to know exactly what her wishes are regarding medication.

"I don't feel I'll be able to make a competent decision under the influence of pain and medicine.

"I want to try to make it clear, so no one is questioning what I want."

If you or someone you know has been affected by the issues in this story, the organisations listed here may be able to help.

Help for Cancer Caregivers, external and Cancer Support Community, external provide information and resources for families in the US.

Marie Curie, external provide help and support to terminally ill people and their families in the UK. Phone: 0800 090 2309.

You can also get in touch with the Samaritans, external who have organisations across the globe.