As a Pittsburgh Jewish community reeled, its teenagers mobilised

- Published

Sophia Levin, one of the speakers, declared: "I am a different Jew today than I was yesterday"

"I knew Neo-Nazis and such people exist and they hate my people, but I never really thought they were around me... I always thought they were somewhere else, I never really processed they were everywhere."

Josh Fidel, and other teenagers living in Squirrel Hill in Pittsburgh, say they never really had to think about anti-Semitism in their everyday lives before Saturday, when it arrived with deadly force at their community's doorstep.

Josh learned about the shooting at a local synagogue a few minutes' drive away from his home before it was reported on the news.

His friend, who lives opposite Tree of Life, had received frantic calls from his parents telling him about it. They told him they were locked in their basement and their attic was being used by police snipers.

The alleged gunman, Robert Bowers, was eventually taken alive by authorities, but injured. He had killed 11 people inside the synagogue before he was captured, all of them aged between 54 and 97.

"My parents knew most of the families," Josh says. "There's not a single Jew in Pittsburgh or even the whole country who isn't affected by this. It hurts everyone."

Another local teenager, Marina Godley-Fisher, who lives only a block away from the synagogue, says she was shaken awake by a neighbour.

"They woke me up and said: 'Hey the police are telling us to stay inside and lock the doors and get away from the windows'," she tells the BBC.

"I never thought it would be so close to home, and never in a synagogue, I guess."

Josh Fidel, 17, is pictured with his brothers Matt (left) and Noah (right)

"I've always known in general Jewish people are a minority, but in Squirrel Hill they're not," she adds. "I didn't think we'd have much to worry about."

Squirrel Hill is Pittsburgh's long-standing Jewish hub - both geographically and institutionally - with half of the city's 50,000 Jewish population living in the neighbourhood and its surrounding areas.

Residents say it's a place where all faiths and denominations, from Orthodox to secular, live side-by-side and many know each other well.

As the community began to learn they had suffered what is believed to be the worst anti-Semitic attack in US history, some of its teenagers began texting.

They already had a group message in place from a school walk-out they helped organise earlier this year.

They, like thousands of others across the US, had walked out of their institution to protest against deadly gun violence and what they see as government failure to prevent it.

They say they felt passionately because of their fear that a local mass shooting could one day become a reality - and on Saturday it did.

"It's so frequent that I'm used to it, almost numb to it. It's almost routine," 17-year-old Rebecca Glickman says, about the prevalence of US gun violence.

"It's a horrific crime scene. One of the worst, and I've been on plane crashes"

"When I go to the movie theatre, when I go to school, when I go out with my friends to the mall.... When I go anywhere, I'm always thinking of it happening to me."

Another high-school senior, Emily Pressman says: "You never expect it to happen to you until it does,"

"You see it on the news and you think it's a tragedy but now I'm looking at the news and I'm seeing my home."

She learned of the shooting while taking part at a debate competition about 15 miles away when she and her friends received frantic calls from family checking they were safe.

Marina (left) and Emily (right) together before the attack

She says when she got back from the event, she returned to an area in lock-down. The local police command centre had been set up on her local street.

Emily recalls sitting at home for 20 minutes, still in her debate dress, feeling "helpless and hopeless".

"We were like: we have to do something. Because we felt so alone, and so distraught and empty and we couldn't sit still," she says.

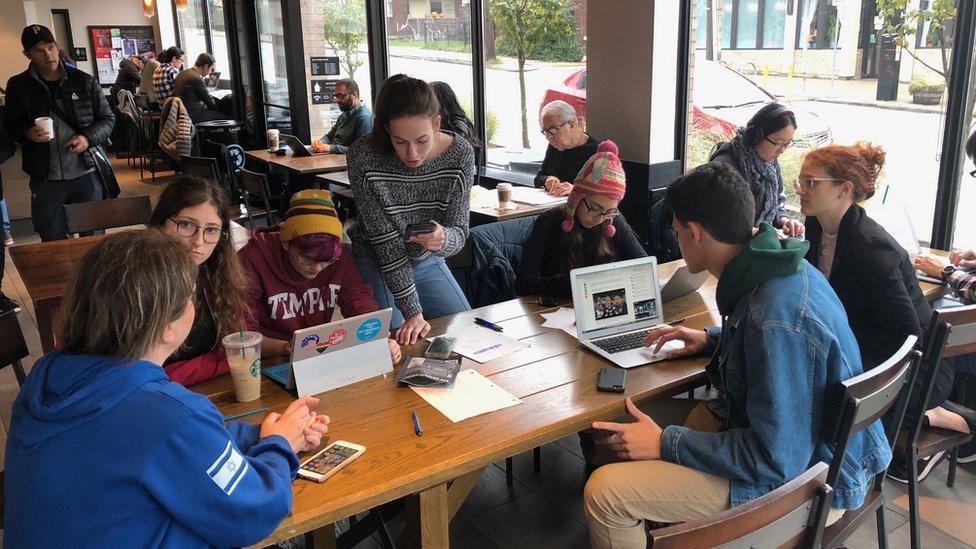

Within a couple of hours, a small group from Taylor Allderdice High School, along with members of the Dor Hadash congregation who used the synagogue, met in a Starbucks.

Despite having no experience of organising big events, they decided to plan a gathering that night.

They hoped a public vigil could offer a place for the close-knit and distraught community to unite to seek comfort from each other.

By 14:00 on Saturday, the students were gathered together organising

From the coffee shop, they called journalists and newspapers and mobilised other local young people on social media.

Within a few hours, through friends and family, they had secured a microphone, flowers, candles, and wood for a make-shift stage.

At one point, they faltered, worried they were being disrespectful to the victims and were concerned about stepping on community toes in taking the lead with organising.

But by evening time, when they gathered for the vigil at 17:30, more than a thousand people turned up.

They opened with a Mi Sherbeirach, a prayer for healing, as crowds packed into a local road intersection close to the Pittsburgh Jewish Community Centre.

The vigil attracted people of all faiths, who in the rain prayed, mourned and sang together in an unexpectedly large, and somewhat spontaneous, display of unity.

'More aware of being Jewish'

One student, 15-year-old Sophia Levin, stood in front of the crowd and declared: "I am a different Jew today than I was yesterday."

"Yesterday being Jewish was just being a part of the Jewish community. Hearing about anti-Semitic [events] was something you heard about other places. But this is Squirrel Hill, and that didn't affect us here," she told them.

Emily and Rebecca both agree the experience has changed how they view their Jewish identity.

Crowds sing at a vigil in Pittsburgh

"I'm now more aware of being Jewish than I was," Emily says.

"It doesn't matter who you are, it's just a label, but people want to hurt you for that label. But I don't think anyone should hide who they are."

Rebecca says a day on, the mood around the neighbourhood is still fearful, but they also feel very loved and supported.

"I don't think it's a good thing to live life in fear and I don't think most people in this community will," she says.

"I just think you have to be aware of peoples' biases toward you and you have to fight for who you are in your daily life."

'We are not going to stand idly by'

The group say they hope to do more to support the community and want to continue to advocate for better gun-control legislation nationally.

None of them will be eligible to vote in the mid-term elections in nine days. Some will be short of their 18th birthday by just a few weeks - it's a source of frustration, but motivation too.

"Parkland sort of set the precedent that students have a voice, that we are not just going to stand idly by," Josh says.

"Students are starting to learn if they want to make a change they have to do it themselves, because they can't just rely on politicians."

- Published28 October 2018

- Published27 October 2018

- Published28 October 2018

- Published27 October 2018