Mid-terms 2018: When an attack ad is a vote decider

- Published

Attack ads are broadcast on radio and TV, and increasingly on social media

Personalised take-downs, scary buzzwords, and horror film music - the political attack ad is an inescapable part of American elections.

In these mid-terms, we've seen candidates' siblings attack their own, a radio ad from Arkansas suggesting "Democrats will start lynching black folks again", and bigfoot deployed in search of a Republican candidate in Minnesota., external

And no-one could forget the Demon Sheep ad of the 2010 campaign, external.

"Campaigns use them because they work. Every bit of data shows that the negative spots work better than positive spots," says political commentator and former Republican strategist Liam Donovan.

Millions of ads are churned out in election cycles, broadcast on radio, TV and increasingly on social media. Around $8 billion could be spent on political advertising, external across all races this year, according to a prediction by Borrell Associates.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But with many feeling 2016 election left civility and truth in tatters, some voters are seeing attack ads differently.

We speak to independent voters who say they will vote next week for the candidate with the least aggressive ads.

This story came from a discussion by members of a BBC News Facebook group about the midterms.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Anne, Dave, Claire and Martin live thousands of miles from each other on opposite coasts of America, but they all agree on one thing - they are sick and tired of negativity.

As non-partisan voters without loyalty to a party or issue, their opposition to attack ads will define how they will cast their ballot on Tuesday.

"They really are my kryptonite and they are getting worse," Anne Berriman, a stay-at-home mum, explains. During one short advert break last week, she counted six attacks ads.

Charity worker Claire Crawford, 62, who lives near Atlanta, Georgia, agrees: "I will prefer to vote for the candidate who rises above the 'dirty' politics. If you have nothing nice to say, say nothing."

Anne Berriman, 53, lives in Austin, Texas

"Tell me what you're bringing to the table instead of highlighting what the other person isn't," is 51-year-old Martin McShea's message to candidates in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he works as a locomotive engineer.

And Dave Miller, a software engineer in Washington state, admits that attack ads work on voters who don't take time to research issues. For him, "all things being equal" he would choose the least negative candidate.

Anne says two ads stand out in Texas, where incumbent Republican Senator Ted Cruz is battling wildly popular challenger Democrat Beto O'Rouke.

From the Cruz camp, one ad accuses O'Rourke of being anti-police, external and "divisive and dangerous".

An ad paid for by O'Rourke meanwhile attacks Cruz for his opposition to expanding healthcare provision.

What you need to know about the mid-terms

Watching them makes Anne "fearful" and want to "turn away from the election". That's her reason for opposing their use so strongly.

"The ads foster division in our communities. They encourage people to see people they disagree with as enemies - the effect ripples all the way down," she says.

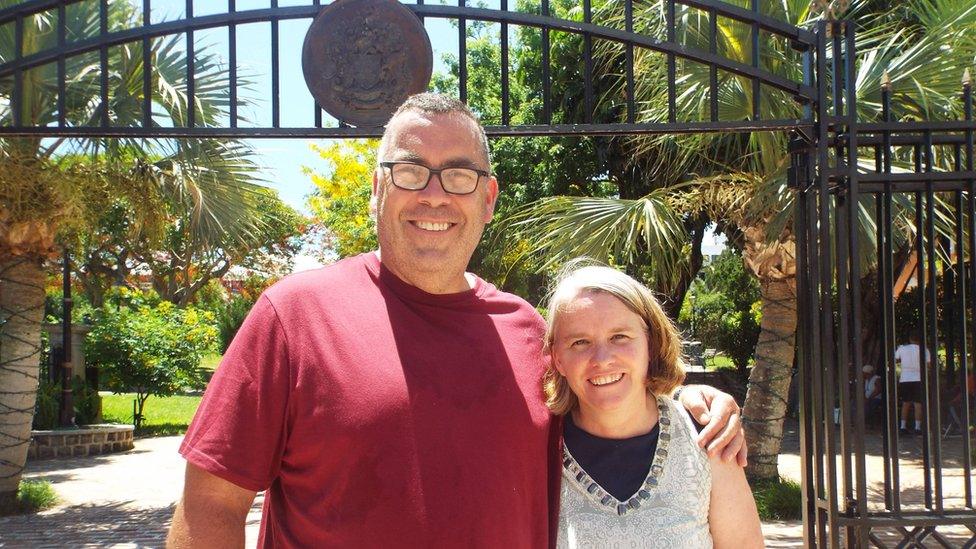

Claire, 61, is a retired IT worker in Georgia

In Pennsylvania, Martin says this is the first time he will take attack ads into consideration when voting.

"2016 had so much negativity and a lot people are tired of that. The Senate Democrat candidate here has done hardly any attack ads - she's trying a different thing and I really like that."

But Dave doesn't think they have impact beyond the election, and instead blames the broader political system for "pushing people further part."

Commentator Liam Donovan says that in this election, Democrat challengers have been able to capitalise on voters turned off by the extremes of 2016 by using more positive messages:

"It's easier to do as challenger than as an incumbent. The party in power is on attack."

The other small difference this year in comparison to previous elections it that with so many negative ads running, a candidate cut could through the noise by running a positive one, he claims.

Ads may play loose with the truth, but Dave argues they are useful tools for revealing who's pulling the strings.

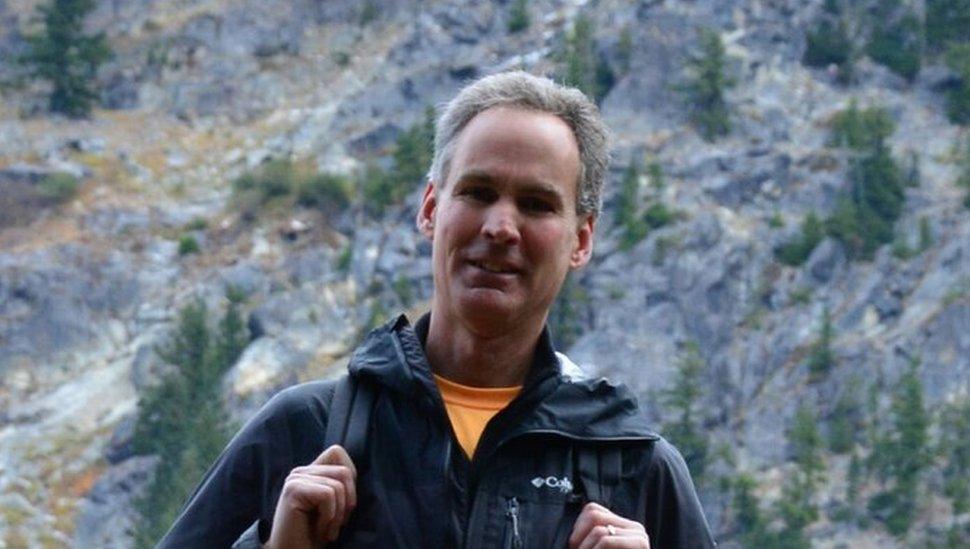

Dave Miller is a software engineer in Washington state

"When I see an ad, I'll research who is funding it. If the backers aren't working in my interest, I think twice about supporting the candidate."

In Georgia, where Claire lives, attack ads in the governor's election accuse Republican candidate Brian Kemp of supporting voter suppression and others highlight Democrat candidate Stacey Abrams' personal debt., external

Unlike the ads in many states, she believes these attacks are rooted in some truth and watching them prompts her to research the candidates.

Martin agrees: "Getting to the truth now is really important - there's so much stretching of information now. Ads make you do the homework and ask what are they hiding or what are they actually bringing to the table."

But Anne and Claire don't believe they are a good way of raising political issues or potential problems in a candidate.

"I don't take well to being badgered, lied to, or talked down to," Claire argues.

Martin McShea is a locomotive engineer in Lancaster, Pennslyvania

Anne believes that the negativity of these ads contributes to low youth turn-out: "That frightens me. You have to see the positivity, and if you don't, then you think what's the point?

If attack ads are prompting voters to research candidates, doesn't that make them effective tools? Anne says no.

"There are better ways to do it. A candidate could explain their own position on, for example, healthcare, and mention that their opponent has a different approach," she suggests.

Claire agrees: "I'd rather hear how a candidate truthfully and honestly plans to assist our state and citizens."

But those hoping for more positivity in American political advertising are likely to wait a long time say experts.

"It's going to get worse in 2020 - it's a one-way ratchet. Attack ads will work until we finally vote with our feet," argues Mr Donovan.