Why did Trump's love affair with US generals turn sour?

- Published

Mr Trump's initial picks for his administration heavily relied on high-profile military men

Apparently, among President Trump's favourite movies is the Second World War epic Patton: Lust for Glory.

General George Patton was a charismatic, no nonsense and hard-fighting kind of officer. He got results but he was also self-absorbed and controversial - twice striking soldiers suffering from combat stress.

Is Patton perhaps, in the president's mind, the archetypal general? If so, then he will have been deeply disappointed by the raft of generals whom he appointed to his administration.

Indeed, we know that he was because he has said so, most recently castigating General James Mattis - his defence secretary - as a failure, who he had "effectively fired". General Mattis, of course, actually resigned.

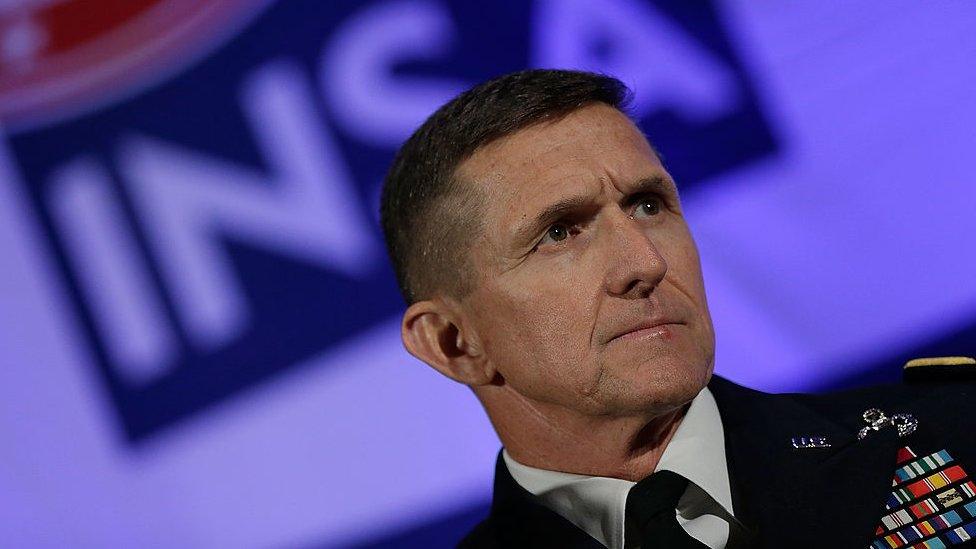

Let's set aside Mr Trump's first national security adviser, General Michael Flynn, who did indeed have to fall on his sword. He was forced to resign in February 2017 after lying to Vice-President Mike Pence over his contacts with the Russians.

The most noteworthy aspects of Mr Trump's initial picks for his administration were his heavy reliance upon high-profile military men.

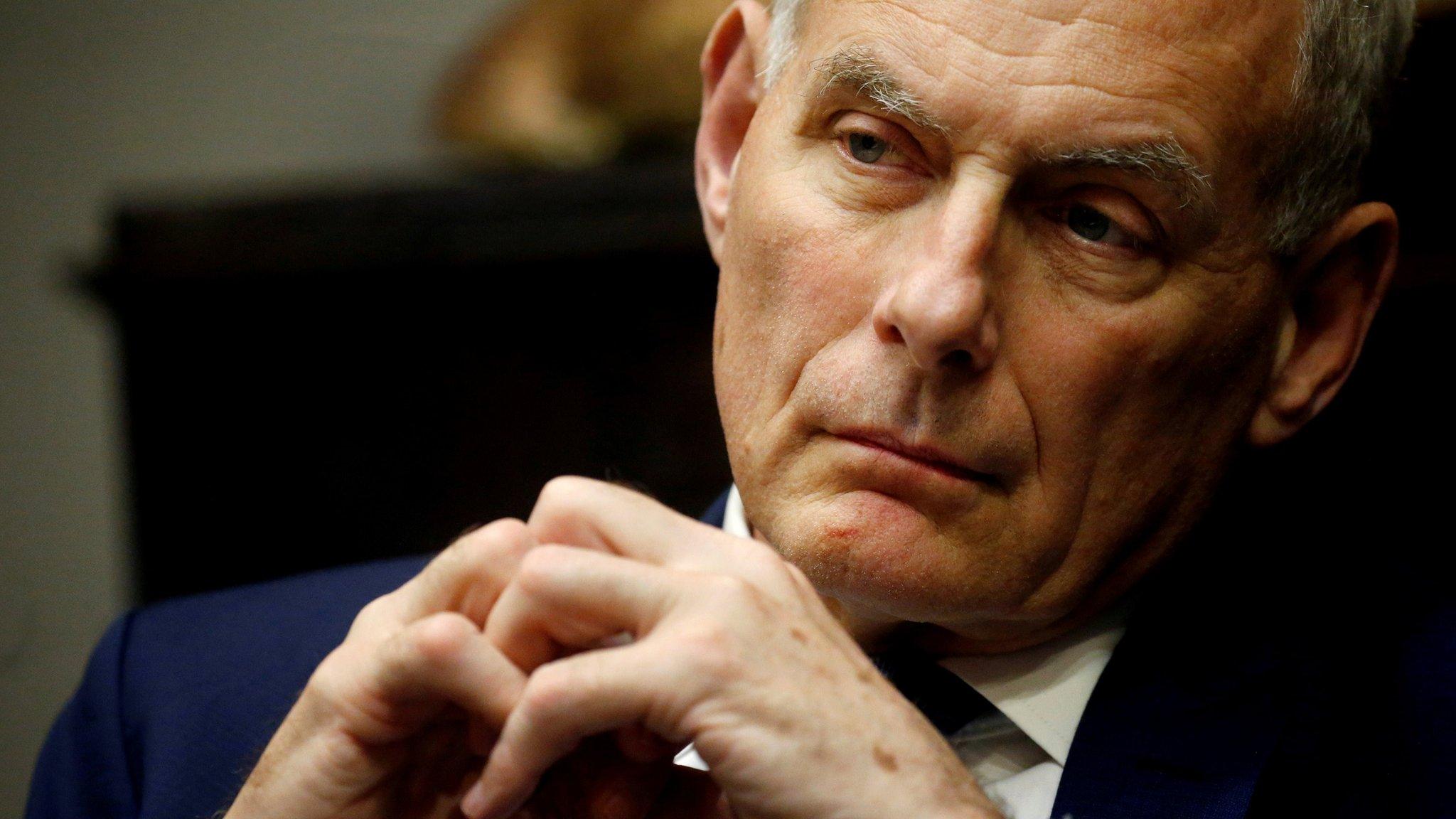

Retired Marine Corps General John Kelly was appointed as Secretary of Homeland Security, before subsequently becoming the White House chief-of-staff.

Another senior Marine General, James Mattis, became defence secretary, and the errant Michael Flynn was replaced as national security adviser by the widely respected and innovative military thinker, Army General HR McMaster.

Chief of Staff John Kelly (r) is the 28th person to resign or be fired during Mr Trump's administration

Fast forward to the end of December 2018 - all three men, first Gen McMaster in March, then Gen Kelly and finally Gen Mattis, have all gone. This is no surprise. It was seen as being almost inevitable when I spoke to a raft of experts a year or so into the Trump administration's tenure.

Their argument was that the president would prove impossible to brief and ignorant of detail.

Ultimately the military men would be forced to choose between the code of values that they had followed during their professional careers rather than adopting those of the property magnate and reality TV show star who now sat in the White House. And so it has proved.

Why then was Mr Trump so enamoured by the military in the first place?

Would the US military disobey a nuclear order from President Trump?

It should be remembered that it was the context that made the generals' roles so significant in this administration, not that they came from the military as such.

It is often forgotten that President Obama too had his raft of former military appointees, among them his first national security adviser and secretary of veterans affairs, both of whom were ex-generals.

But what made the Trump team so different was the fact that many Republican-leaning foreign policy experts refused at the outset to have anything to do with it.

Mr Trump had to cast his net wider and given his own peculiar view of the sort of gutsy leadership provided by generals like Patton, then why not draw on America's contemporary warrior caste?

Mr Trump himself of course has never served in the military. The closest he came to the armed forces was during part of his education at a military-style academy.

He received five draft deferments (four for education and one on medical grounds) that meant he did not have to serve in Vietnam. But his fascination with military men is almost palpable.

In his recent televised cabinet session he spoke admiringly of the military's upper echelons.

"When I became president," he noted, "I had a meeting at the Pentagon with lots of generals. They were like from a movie. Better looking than Tom Cruise, and stronger." No wonder then he sought to fill out key posts with military men.

Army Lieutenant General HR McMaster (l) was replaced as national security adviser after just over a year in the job

The trio of Mattis, Kelly and McMaster were part of a small group dubbed by some as "the adults in the room". They were supposed to speak truth to power; to curb the president's excesses; reassure allies and so on. And for a period they did.

The president for example may have castigated his Nato allies in public while Defence Secretary Mattis tried, as far as he was able, to reassure them that at a practical level it was pretty much business as usual.

The generals went into this knowing that it was almost mission impossible and one by one they have fallen by the wayside. Serving Donald Trump could be explained away for a time as serving the nation. But as his behaviour remained erratic and his policy decisions mercurial, for each of these men there came a moment when they could no longer remain in their posts.

For James Mattis, for example, it was the decision to unilaterally pull US ground troops out of Syria that was the last straw.

Mr Trump has previously described Gen Mattis, 66, as "a true general's general"

President Trump's Syria decision has been widely criticised by the experts. Some say it is too rapid; others that it lacks any guiding strategy. But - and this is a crucial "but" - it may be popular among ordinary voters.

America's military campaigns in places like Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan have merged in the general imagination into what some call "the Forever Wars" and many Americans are sick and tired of it.

On this issue, as on one or two others, Mr Trump's rationalisation of policy may be adrift but his gut instincts may not.

In choosing military men for such high profile positions, President Trump did not then get what he expected.

As the leading expert on US civil-military relations, Professor Eliot Cohen of Johns Hopkins University, told me, "the most interesting thing in all of this is the fact that the military so deeply embodies the post-World War II American foreign policy consensus."

This means, he explained, that "they believe in our alliance system, in global engagement, in persistent policies (including the Forever Wars), and in preserving the social values of the last half century (note their stand on transgender service personnel). This was not in tune with the president's own outlook."

Eliot Cohen is no fan of Mr Trump. But his expertise is such that he gave evidence before the Senate Armed Services Committee when it met to decide if long-standing restrictions might be waived to allow the relatively recently retired James Mattis to take up the post of defence secretary.

"Mr Trump", he says, "has an adolescent view of the military as a bunch of tough guys who, moreover, would be personally loyal to him. Again and again, he has found out that they really aren't that way."

- Published27 December 2018

- Published27 December 2018

- Published27 December 2018

- Published8 December 2018

- Published22 March 2018

- Published18 June 2020

- Published25 November 2020

- Published15 November 2017

- Published2 December 2016

- Published2 December 2016