Report: US 2018 CO2 emissions saw biggest spike in years

- Published

Climate change: How 1.5C could change the world

A new report has found that US carbon dioxide emissions rose by 3.4% in 2018 after three years of decline.

The spike is the largest in eight years, according to Rhodium Group, an independent economic research firm.

The data shows the US is unlikely to meet its pledge to reduce emissions by 2025 under the Paris climate agreement.

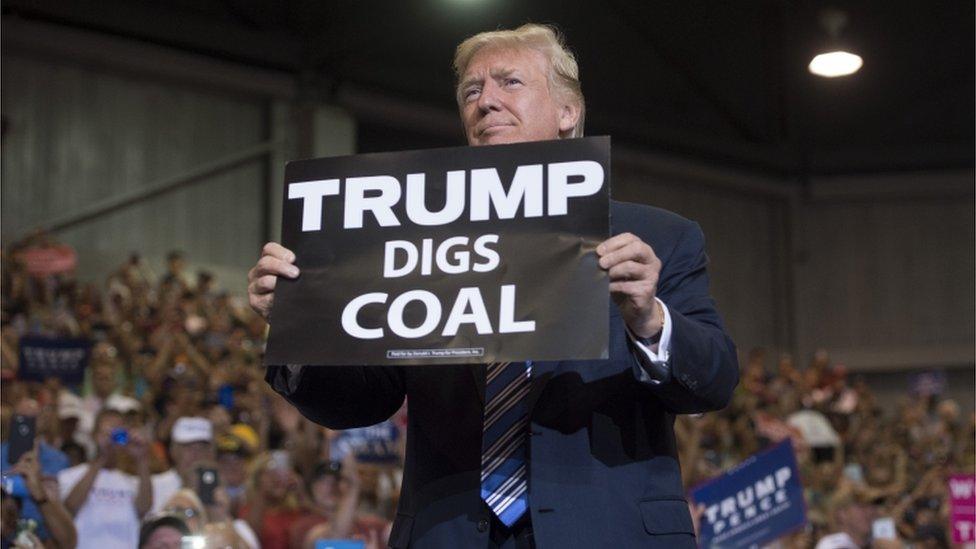

Under President Donald Trump, the US is set to leave the Paris accord in 2020 while his administration has ended many existing environmental protections.

While the Rhodium report notes these figures, external - pulled from US Energy Information Administration data and other sources - are estimates, The Global Carbon Project, another research group, also reported a similar increase in US emissions for 2018, external.

The US is the world's second largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Exhaust rises from the stacks of the Harrison Power Station in Haywood, West Virginia

And last year's spike comes despite a decline in coal-fired power plants; a record number were retired last year, according to the report.

The researchers note that 2019 will probably not repeat such an increase, but the findings underscore the country's challenges in reducing greenhouse gas output.

In the 2015 climate accord, then President Barack Obama committed to reducing US emissions to at least 26% under 2005 levels by 2025.

Now, that means the US will need to drop "energy-related carbon missions by 2.6% on average over the next seven years" - and possibly even faster - to meet that goal.

"That's more than twice the pace the US achieved between 2005 and 2017 and significantly faster than any seven-year average in US history," the report states.

"It is certainly feasible, but will likely require a fairly significant change in policy in the very near future and/or extremely favourable market and technological conditions. "

What's behind the rise?

Analysis by Matt McGrath, Environment correspondent, BBC News

There are a number of factors behind the rise in US emissions in 2018, some natural, mostly economic.

Prolonged cold spells in a number of regions drove up demand for energy in the winter, while a hot summer in many parts led to more air conditioning, again pushing up electricity use.

However economic activity is the key reason for the overall rise in CO2 emissions. Industries are moving more goods by trucks powered by diesel, while consumers are travelling more by air.

In the US this led to a 3% increase in diesel and jet fuel use last year, a similar rate of growth to that seen in the EU in the same period.

All this presents something of a problem for the Trump administration which has been happy to point to declining US emissions as a reason to roll back many of the environmental protection regulations put in place by his predecessor.

The figures also show that the President's efforts to boost demand for coal have not succeeded yet, with electricity generated from this fossil fuel continuing to decline.

Despite this, there is little to cheer in the US data for those concerned with climate change on a global scale.

Many had hoped that carbon cutting actions at state or city level could in some way keep the US on track to meet its commitments made under the Paris climate agreement.

The latest emissions data indicate that this is unlikely to happen.

What has changed in the US?

The last time the US saw such an increase in emissions was in 2010, as the country recovered from its longest recession in decades.

Part of last year's spike is also the result of economic growth, but new policies have exacerbated the effects of increased industry production.

Mr Trump has rolled back a number of his predecessor's environmental regulations since taking office, appointing climate change sceptics and industry leaders to head US environmental agencies.

As a part of undoing what he called a "war on coal", in 2017, Mr Trump rescinded the Clean Power Plan, which required states to slash carbon emissions to meet US commitments under the Paris accord.

In December, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) pressed ahead with plans to lift restrictions for carbon emissions from new coal plants and asked for public comment on redefining the phrase "causes or contributes significantly to" air pollution.

No more beef? Five things you can do to help stop rising global temperatures

Under Mr Trump's administration, the federal government has also opened up once-protected lands for oil and gas drilling across the US and has proposed ending regulations on fuel standards for cars and trucks after 2021.

"The big takeaway for me is that we haven't yet successfully decoupled US emissions growth from economic growth," Rhodium climate and energy analyst Trevor Houser told the New York Times, external.

The US jump also marks a worldwide trend: 2018 saw an all-time high for global CO2 emissions and was the fourth warmest year on record.

Transportation remains the top contributor to US CO2 emissions

What contributed the most?

Transportation remains the nation's number one source of CO2 emissions for the third year in a row.

But the largest emissions growth came from two sectors "often ignored in clean energy and climate policymaking: buildings and industry".

The report estimates emissions from residential and commercial buildings increased by 10% last year, reaching "their highest level since 2004".

And without significant changes, industrial emissions will become bigger contributors to US CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions.

"We expect it to overtake power as the second leading source of emissions in California by 2020 and to become the leading source of emissions in Texas by 2022."

- Published8 October 2018

- Published8 October 2018

- Published22 November 2018

- Published5 December 2018

- Published29 November 2018