How will history judge President Trump?

- Published

Hostile historians may come to regard Donald Trump's presidency as an aggregation of the lesser traits of his predecessors.

The bullying of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who demeaned White House aides and even humiliated his Vice-President Hubert Humphrey - forcing his deputy once to recite a speech on Vietnam while he listened, legs akimbo, trousers round his ankles, on the toilet.

The intellectual incuriosity of Ronald Reagan, who once apologised to his then White House Chief of Staff James Baker for not reading his briefing books with the immortal excuse: "Well, Jim, The Sound of Music was on last night."

The shameless lies of Bill Clinton about his affair with Monica Lewinsky.

The paranoia of Richard Nixon, who in his final days railed, King Lear-like, at portraits hanging on the White House walls.

The incompetence of George W Bush, whose failure to master basic governance partly explained his administration's botched response to the aftermath of the war in Iraq and also to Hurricane Katrina.

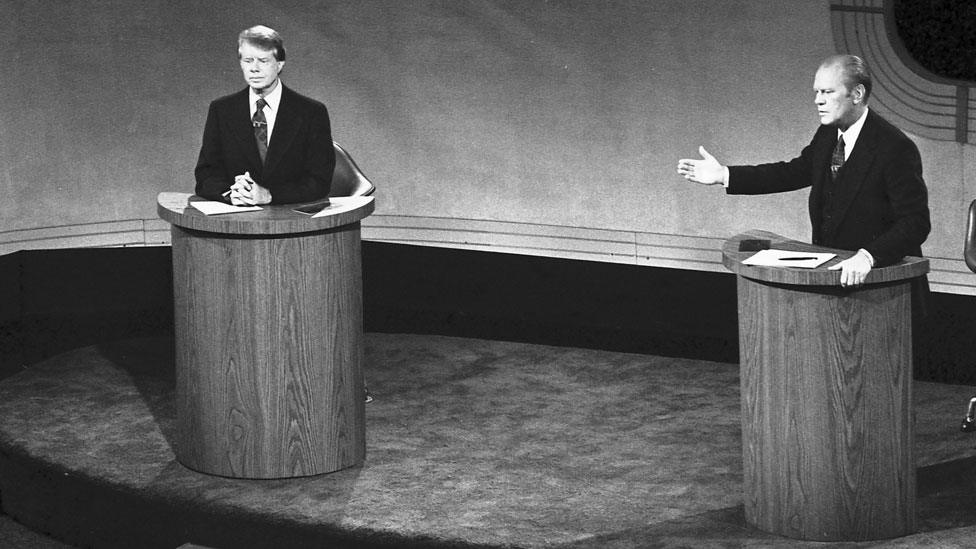

The historical amnesia of Gerald Ford, whose assertion during a 1976 presidential debate that Eastern Europe was not dominated by Moscow was a forerunner of Trump's recent endorsement of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

The strategic impatience of Barack Obama, whose instinct always was to withdraw US forces from troublesome battlefields, such as Iraq, even if the mission had not yet been completed.

Even the distractedness of John F Kennedy, who whiled away afternoons in the White House swimming pool with a bevy of young women to sate his libido, a sexualised version, perhaps, of Donald Trump sitting for his hours in front of his flat-screen TV watching friendly right-wing anchors massage his ego.

Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford at a 1976 debate

At the midpoint of Donald Trump's first term, historians have struggled to detect the kind of virtues that offset his predecessors' vices: the infectious optimism of Reagan; the inspirational rhetoric of JFK; the legislative smarts of LBJ; or the governing pragmatism of Nixon.

So rather than being viewed as the reincarnation of Ronald Reagan or Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Trump gets cast as a modern-day James Buchanan, Franklin Pierce or William Harrison. Last year, a poll of nearly 200 political science scholars, external, which has routinely placed Republicans higher than Democrats, ranked him 44th out of the 44 men who have occupied the post (for those wondering why Trump is the 45th president, Grover Cleveland served twice).

Though the president has likened himself to Abraham Lincoln, who posterity has deemed to be greatest of all presidents, this survey judged him to be the worst of the worst. Even the conservative scholars, who identified themselves as Republicans, placed him 40th.

Were it not for his braggadocio, Donald Trump might receive a more positive historical press. A recurring problem, after all, is that he gets judged against his boasts. He can point to a significant record of right-wing accomplishment.

Tax reform. Two Supreme Court nominees safely installed on the bench. The travel ban. The bonfire of federal regulations. Criminal justice reform. Legislative action aimed at ameliorating the opioid crisis. Nato members ponying up more cash. Annual wage growth is at a nine-year high. 2018 was the best year for job creation since 2015. Many of his campaign pledges, such as the renegotiation of the Nafta free-trade agreement and the relocation of the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, have been kept. Promise made, promise kept is one of his boasts that regularly rings true.

The bruising but successful addition of Brett Kavanaugh (left) to the bench was a huge Trump victory

Often, though, he blunts the impact of authentic good news with inflated claims. US Steel is not opening up six new plants. He is not the author of the biggest tax cut in American history. Besides, the trade war has penalised US manufacturers and farmers, and in 2018 the stock market suffered its worst year since the 2008 financial meltdown.

This market volatility highlights other Trump tendencies contributing to his poor reviews: pointing to a buoyant stock market as a metric of personal success, the downside of which is the downswing; and blaming others when things go south, in this case the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell. Trump sits in the Oval Office behind what's called the Resolute desk, hewn from the timber of an abandoned British warship and first used by John F Kennedy, a former navy man himself. But on it you will not find the desk sign favoured by Harry S Truman: "The Buck Stops Here."

This America First president is himself an American first. Indeed, a further reason for the disdain of historians is because, historically speaking, his administration has been like no other. The chaos of staff turnover - two secretaries of state, two secretaries of defence, two attorneys general, three White House chiefs of staff, and a revolving door of senior West Wing aides. The foreign policy by tweet. The chumminess with adversarial authoritarian leaders, such as Kim Jong-un and Vladimir Putin. The blurring of ethical lines supposedly separating the Trump White House from the Trump business empire. The Russia collusion investigation, which has raised questions, so far unsettled, about his true allegiance.

Read more from Nick

Nor have we ever witnessed a US leader who has so flagrantly flouted the normal rules of presidential behaviour. The playground nicknames. The Twitter tirades. The ugly slurs - "horseface" for Stormy Daniels, a former porn star with whom he was once apparently intimate. In response to indictments in the Mueller probe, he has sometimes sounded more like the boss of a crime family. "A rat" is how he described his former lawyer and fixer Michael Cohen, deploying the lingua franca of the Mafioso.

Though he claims to offer exemplary moral leadership, even conservatives have criticised his presidency for being a profile of amorality, whether in response to the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi or the neo-Nazi torchlight protest in Charlottesville. One of my abiding memories from the past two years came in the lobby of Trump Tower during that extraordinary press availability held a few days afterwards, when he suggested a "very fine people" equivalence between far-right protesters and their opponents. Standing next to me was an African-American cameraman, who abandoned his tripod so that he could join reporters in hurling questions, something that rarely, if ever, happens at press conferences. "What should I tell my children?" he shouted. "What should I tell my children?"

A memorial to Heather Heyer, killed while protesting against white supremacists in Charlottesville

With each bizarre press encounter and each ALL CAPS tweet, it can sometimes feel as if America is living through some historical counterfactual. It is as if the right-wing populist Pat Buchanan managed to beat George Herbert Walker Bush to the Republican presidential nomination in 1992 and, on the strength of his fiery culture war speech to the GOP convention, went on to beat Bill Clinton. Buchanan launched his insurgent campaign with a plea to put "America First" and used the mantra "Make America Great Again." Or maybe the Trump presidency is what a Perot administration might have looked like. Ross Perot, who also sought the presidency in 1992, was another populist billionaire and deep state conspiracy theorist. Yet even Buchanan and Perot, one suspects, would have been more orthodox.

This alternative history feel to the Trump presidency partly explains why some of the dystopian "Could it happen here?" novels, such as Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale and George Orwell's 1984 have received a "Trump bump" in sales. Phillip Roth's The Plot Against America has also become a touchstone work. It imagines as president the aviator Charles Lindbergh, the telegenic spokesman for the isolationist "America First Committee," who turns the USA into a more authoritarian state.

These dystopian analogies, however, are often not analogous. Donald Trump's America is not Margaret Atwood's Gilead, or George Orwell's Oceania. And just as the billionaire unwisely compares himself to the heroes of history, a trait which inevitably invites ridicule, his more strident critics over-reach when they liken him to history's worst villains. He is not a modern-day Adolf Hitler, nor an American Mussolini.

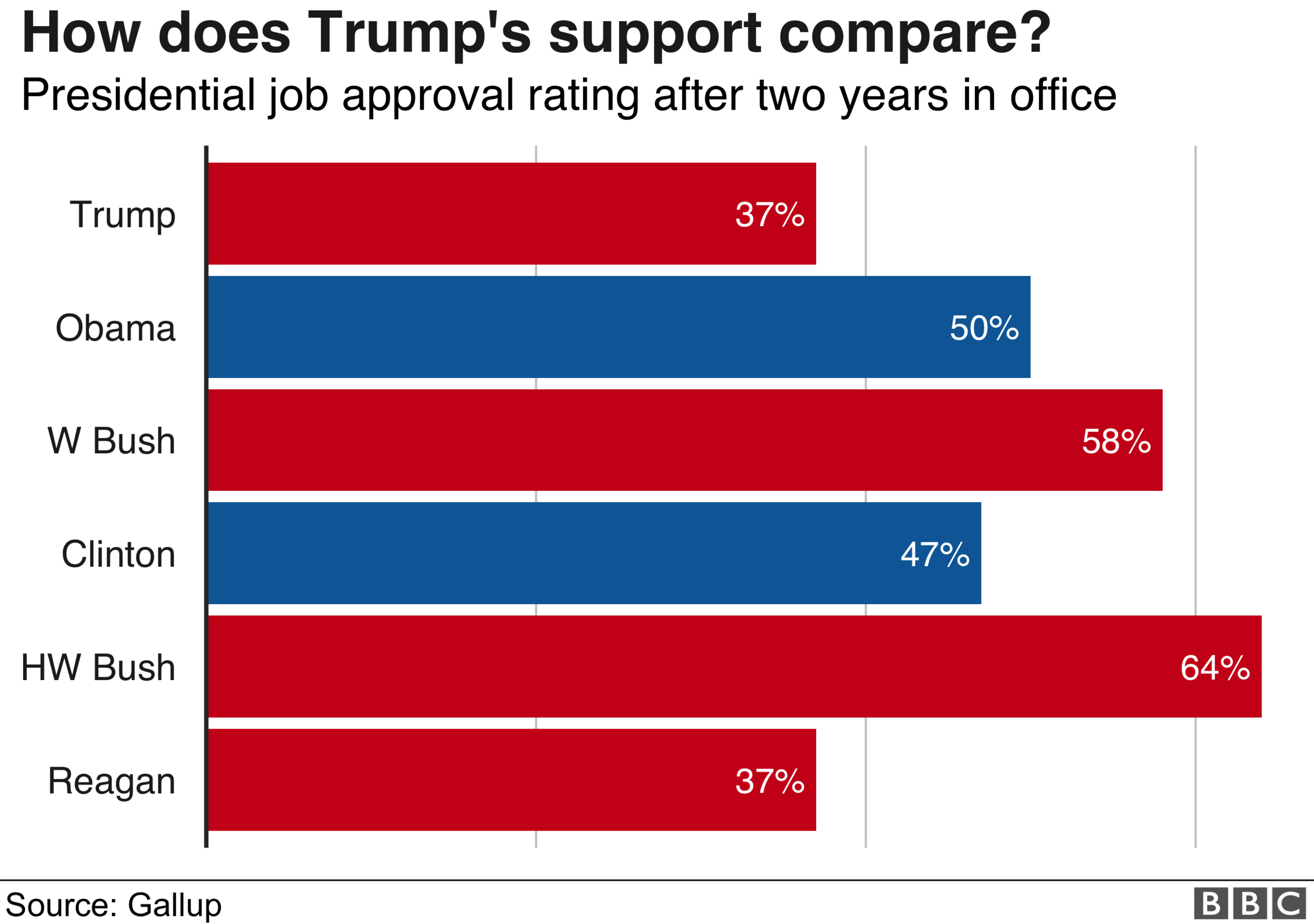

When Donald Trump took the oath of office, nobody should have been surprised that an anti-politician would morph into an anti-president. In 2016 Americans rejected politics as usual. And diehard supporters still throng his rallies, wearing Make America Great Again caps and chanting for him to build the wall and lock up Hillary Clinton. His approval ratings among Republicans remain strong - 88% according to Gallup. His overall approval rating - 37% according to Gallup - is on a par with Ronald Reagan's at the two-year mark.

Yet the rally chants of "four more years" remain a wish rather than a prophecy, and the setbacks suffered by the Republicans in November's congressional elections point to an underlying weakness: the disaffection of moderate Republicans, who were never enthusiastic about Donald Trump but who refused to countenance Hillary Clinton as president. Trump remains the only president in the history of the Gallup poll not to crack the 50% threshold.

Because Donald Trump is unwilling to accept he is anything other than an A+ president, the grade he has bestowed upon himself, he is not prepared to adopt the kind of correctives that have saved troubled presidencies. JFK learnt from the disaster of the Bay of Pigs and the bullying he received from Nikita Khrushchev at the Vienna summit in 1961, which was followed in short order by the Soviet construction of the Berlin Wall. Confronted a year later with the Cuban Missile Crisis, he was less trusting of his generals, who urged airstrikes, and less willing to be pushed around by Khrushchev.

More on the Trump presidency

Bill Clinton, who was accused of liberal over-reach during his first months in office and was punished as a result in the 1994 mid-term elections, tacked back to the political centre in time to win re-election in 1996. This is not a learning presidency.

Incumbents can also benefit from self-doubt, a trait Donald Trump seems to regard as a character flaw. Presidents also usually grow in office. But while there are physical signs the 72-year-old is ageing - unable to holiday in Florida over Christmas, he has looked especially tired these past few days - there is little sign he is maturing.

It does not help that so many senior figures within his administration and his party treat him like a child monarch. The cabinet meeting where holders of the highest offices of state went around the table lavishing praise upon the president felt like Pyongyang on the Potomac. Vice-President Mike Pence has perfected the devoted gaze of the prototypical political wife. Senior Republicans, who privately roll their eyes, have been admiring, even sycophantic, in his presence.

For the most part, international leaders have also opted for obsequiousness. Not only did Theresa May rush to Washington to invite Trump for a state visit - a state visit that has still not been diarised - she telephoned him on Air Force One to congratulate him after the mid-term election, even though the Democrats regained the House of Representatives. All this after Trump has frequently undermined her leadership over Brexit and trampled over the special relationship. One of the reasons Mr Trump is said to look so contemptuously upon Angela Merkel is because she makes so little effort to conceal her contempt for him.

At the two-year mark, it is usually clear how incumbents will leave their mark on the presidency. After the torpidity of the Eisenhower years, Kennedy made the office more youthful and glamorous. Johnson, that shrewd "Master of the Senate", brought the executive and legislative branches into closer alignment. Nixon consolidated more power in the White House, accelerating the trend the liberal historian Arthur M Schlesinger Jr dubbed "the imperial presidency."

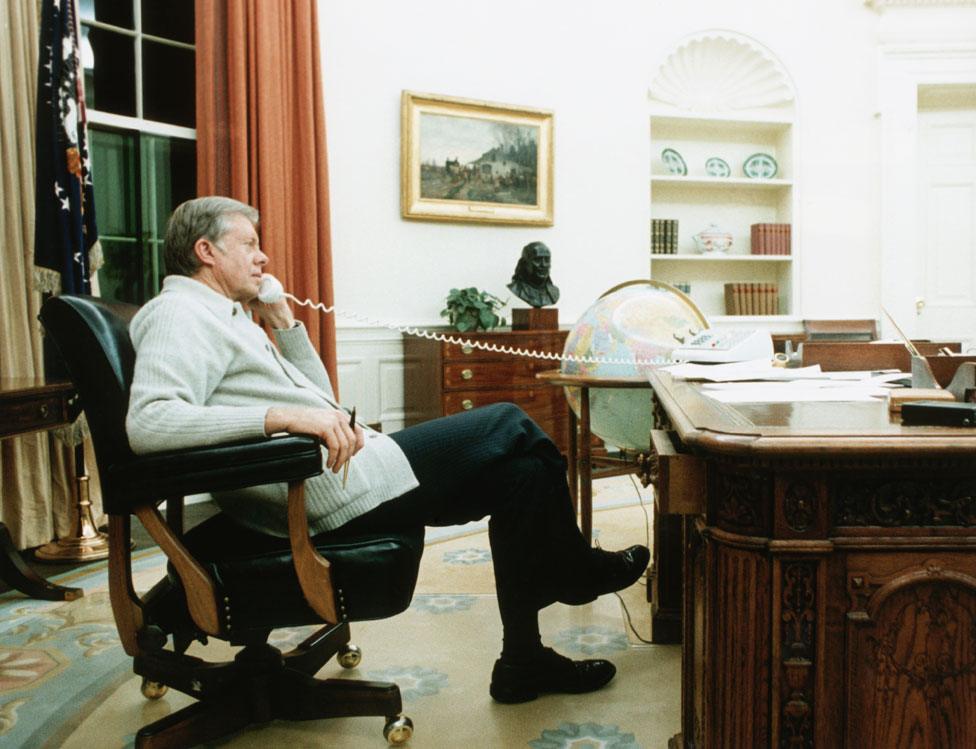

Ford reversed much of that process, even going as far to drop the playing of "Hail to the Chief" when he made an entrance. The cardigan-wearing Jimmy Carter, who used to go from room to room turning off lights to save energy, suburbanised the White House. Reagan, who restored many of the ceremonial trappings, erased the lines between politics and entertainment.

Clinton, in the age of Oprah, made the office more empathetic, narrowing the emotional distance between the presidency and the people. Obama set a new standard for ethical behaviour - motivated in part by the African-American mantra of working twice as hard to get half as far - and also made the presidency more hip.

Jimmy Carter in the Oval Office

By abrogating behavioural customs, Donald Trump has made the presidency more uncouth and less trustworthy. By departing from executive and managerial norms, he has made domestic and foreign policy-making more impulsive and disorderly. By fraying traditional alliances, he has made the US presidency more isolated. By threatening to declare a national emergency in the funding row over his wall along the Mexican border, he has also indicated a willingness to discard constitutional norms that could mean exceeding constitutional limits.

The cumulative effect of this has been to make the Oval Office a focal point of perpetual turmoil and uncertainty, with the White House hostage to the changing whims and temper of its occupant. Governing sometimes feels secondary to winning political and cultural battles, and slaying opponents. His presidency has become a roiling permanent campaign.

Will his impact bring about more permanent changes? That will depend, to a large extent, on whether or not he wins a second term. Defeat in 2020 would represent a repudiation of his leadership style. Victory would be validating. Yet even as a one-term president, Trump would have changed the character of the presidency and US politics more broadly.

While it is hard to imagine America's 46th or 47th presidents unleashing the same barrage of insults, there are already signs of a "Trump effect" on political discourse. Many mid-term races featured unusually ugly rhetoric. Hours after being sworn in as a new Democratic congresswoman, Rashida Tlaib used a profane epithet as she called for the president's impeachment.

What is known as the Overton window, the broadly agreed parameters of acceptable public discourse, has shifted to the right. I well remember the moment during the 2016 campaign when an email from the Trump campaign dropped into our inboxes announcing he would ban all Muslims from entering the United States. Initially we thought it might have been a hoax, for it seemed so far outside the mainstream of American political thought. Now, though, calls for a Muslim ban would raise eyebrows and provoke protests but hardly drop jaws.

The phrase "Trump has normalised the abnormal" has itself become a cliché. Still, though, I am constantly struck by how many Trump stories and scandals that ordinarily would have launched months, even years, of critical coverage for previous presidents sometimes barely last a single news cycle.

Mattis or Tillerson may have more to say about their time in government

More long-lasting could be the debasement of facts as the basis for debate and policy formulation. By its own admission, this administration has sometimes deployed what the White House aide Kellyanne Conway memorably labelled "alternative facts", starting on day one with false claims about the size of the inauguration crowd. Since then, the Washington Post has listed more than 7,000 presidential falsehoods. But an unsettling lesson of the Trump presidency is that post-truth politics can be highly effective, especially when it comes to shoring up a political base.

As for chaotic governance, future administrations will surely be more stable in terms of staff turnover, and more orderly when it comes to forming and executing policy. But it is easy to imagine Trump's successors pushing the bounds of executive authority in ways that breach constitutional norms, especially now that gridlock on Capitol Hill has become such a permanent feature of Washington politics.

Obama, to a howl of protests from congressional Republicans, relied heavily on executive orders, the flourish of his presidential pen. Trump has gone a big step further by threatening to invoke emergency powers to bypass a hostile Congress. Stress tests for the US constitution, even full-blown constitutional crises, could easily become more commonplace.

The Trump presidency's first drafts of history - most notably Bob Woodward's bestseller Fear - have painted a portrait of unprecedented dysfunction. If former senior administration officials pen honest participant histories - say former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, ex-Secretary of Defence James Mattis or former chief of staff John Kelly - they are likely, if their parting comments offer any guide, to add more detail and texture to that same picture.

If some of the renowned presidential biographers turn their attention to Trump - maybe Jon Meacham, David McCullough or Michael Beschloss, who in the past have rescued the reputations of under-rated presidents such as George Herbert Walker Bush and Harry S Truman - they are unlikely to deliver laudatory manuscripts.

The histories already written, along with those taking shape, will someday be housed in the Donald J Trump Presidential Library, an addition to the 13 existing presidential libraries that form part of the National Archive.

Will it be a landmark to US greatness or a modern-day American folly? Even with two years left to run of this history-defying presidency, most Americans, one suspects, have already made up their minds.

Follow Nick Bryant on Twitter, external

.