How Hispanics are affected by wall debate

- Published

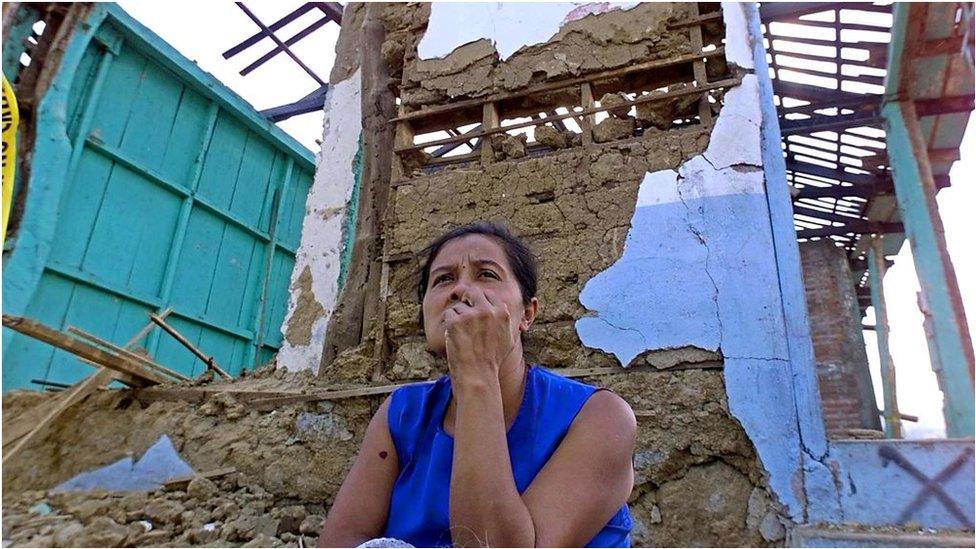

Lindolfo Carballo and Daisy Sánchez at the Wheaton Welcome Centre

Central American immigrants have found themselves at the centre of US news in recent months - the wall, the caravans, the so-called Dreamers. Vicky Baker goes to see how it is impacting on one Latino community in Maryland.

El Catrachito looks like a classic US diner: chrome fittings and a counter top, bar stools and booths.

Yet on the menu, rather than hamburgers and milkshakes, you'll find Central American staples: baleadas (filled tortillas), tajadas (fried plantain), pupusas (fluffy corn pancakes). A Honduran flag is draped across the back wall, and all the patrons are speaking Spanish.

The restaurant is in Wheaton, a small town in Montgomery County, Maryland, which has a particularly large Latin American population.

The last census, in 2010, estimated the Hispanic community at 42%. Among its shopping parades, you'll find Salvadoran bakeries, Peruvian chicken joints and a grocery store called Mi Familia Mercado Latino.

"It is eclectic here," say Omar Lazo, who runs Salvadoran restaurant Los Chorros, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. "It is all mom-and-pop businesses. Hardly any chains."

Pupusas - a Central American speciality - on a grill in Wheaton

Like many people in the area, he feels that Latino people are being used as a bargaining chip between politicians, while having very little high-level representation of their own. He says he finds the current top stories - with the President Trump ramping up talk of a migrant "crisis" and the "dangerous" caravans - hard to watch.

Omar's parents came from El Salvador in the 1970s, starting the restaurant some years later, and he was born in the US. "All you hear is that it is an invasion," he says. "But that's my family, my community. It's dehumanising."

However, he says he hasn't felt any backlash personally that he could link to Mr Trump's language.

"People don't look down on us round here," explains the restaurateur, who also serves on the board of the local chamber of commerce. "They see our people working on construction sites in the freezing cold. They know they can trust their cleaner with their house keys."

A statue called The Commuter stands outside Wheaton station

Wheaton is prime commuter land. Washington DC's metro extends here, and Baltimore lies just to the east. With new apartment blocks springing up and a long-awaited new metro line under construction nearby, there are indications that gentrification could be around the corner.

Currently, short strings of unfussy shopping parades spread out beside wide roads. Amid them stands the Wheaton Welcome Center, freshly painted in yellow and blue, and offering support for immigrant workers.

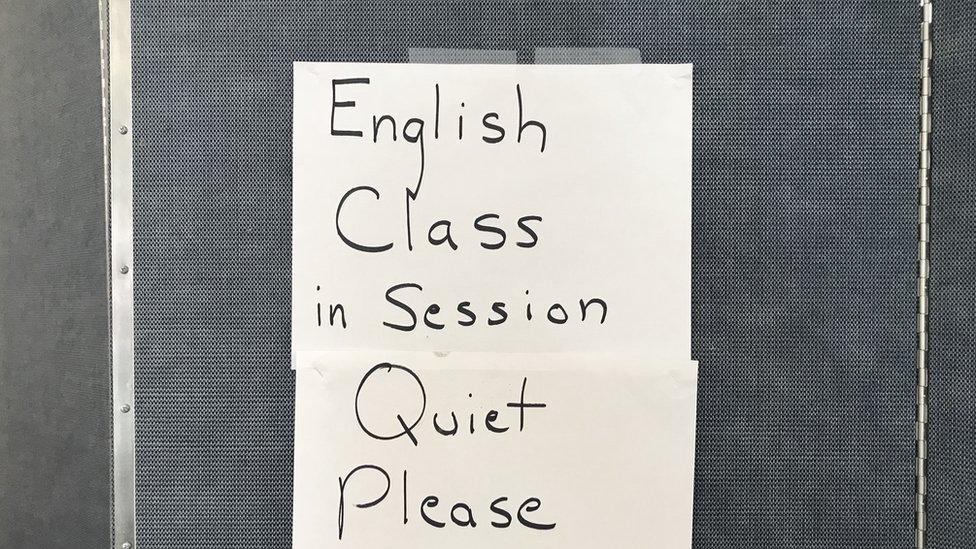

By 6am every day, a mixed crowd of labourers has gathered in its reception hall. Local employers - mostly homeowners - know they can come here to find a worker for short-term jobs. The centre is part of Casa de Maryland, an advocacy organisation that began life as the Central American Solidarity Association of Maryland in the 1980s.

"It is open to everyone, not just Latinos," assures one of its directors, Lindolfo Carballo, pointing out a Malawian artist, who has painted a mural on the wall.

Much of the chatter inside is from Salvadorans. They are the biggest immigrant group in the area. Some came as economic migrants in the 1970s, a larger wave came over to escape civil war and more followed after devastating earthquakes in 2001. It was the natural disasters that led to them being granted temporary protected status (TPS), giving them working rights and halting deportations.

Nowadays some Salvadoran-Americans in this area are second, or even third, generation citizens, but others rely on TPS, which has to be renewed every two years, or another Obama-era programme, Daca, which protects young people who came to the US as children.

Their future feels up in the air after the Trump administration has made moves to rescind both schemes (even though they were recently back on the table as part of a proposed deal in exchange for the border wall).

Currently, the schemes are still operational - largely due to court challenges launched by Casa and other advocacy organisations.

Other presidents got money for a border barrier - why not Trump?

"None of this [debate] is actually new," says Mr Carballo, who came to the US from El Salvador in the 1990s. "The wall is not new. There is already a huge wall on the border, and Trump didn't build it. Deportations are not new either. They used to call Obama the deporter-in-chief."

What has changed is the tone, he says, and he has felt the repercussions personally. A couple of diners told him to "go home" when he was visiting an Italian restaurant recently. They had approached him to ask about the Central American migrant caravan, which President Trump has made a central talking point.

Mr Carballo also says he refuses to use the word "caravan". "It makes it sound fun, when it's actually an exodus."

On a local level, Casa de Maryland says it has support and the county council has helped it acquire funding for the new welcome centre, which opened in November. However, there have been some complaints from critics who believe the day-labour centres encourage undocumented workers. In 2007, one of its centres was hit by an arson attack.

Mr Carballo insists that if people did not use their premises to find workers, the same transactions would happen on street corners, which would leave immigrants open to exploitation. By coming here, they get help getting their tax numbers and they get legal support if they aren't paid. Checking documents, however, is down to the employers.

Daisy Sánchez, a regular at the centre, was a nurse in El Salvador before coming to the US in 2000.

She tries not to let the news get her down. "I am educated, from a good Christian family. I'm not a thief. They need us here," she says.

She has taken all the training courses the centre offers - plumbing, construction - and now paints houses for a living and remains optimistic. "Life is beautiful, it is like a novella, every day is different."

On this particular day there is no work for her, but she will return at 6am tomorrow.

Daca recipients: 'Life in the US is like a rollercoaster'

Javier Solis, who is originally from Ecuador, runs nearby accountancy firm Los Taxes, with his Salvadoran wife, Maria. "We should be allowing undocumented people - who already pay millions in taxes - the chance to be part of the system. Those who haven't even got as much as a parking ticket," he says. "We should be working together, Democrats and Republicans."

He mentions Nancy Navarro - the county's first Latina councillor - as a positive local role model, and he also cites Maryland's Republican governor, Larry Hogan, who is "active with the Latino community" and has distanced himself from President Trump's rhetoric.

Omar Lazo manages Los Chorros restaurant in Wheaton

Omar Lazo says he was not even surprised when President Trump reportedly said El Salvador was a "shithole" country. "No-one knows anything about El Salvador," he says. "They only think of the gangs."

The president has taken to regularly name-checking the MS-13 gang when warning about the risks of migration from Central America. He did so again in his recent post-shutdown speech, when his wall plan failed to go through.

The gang started in the US but has roots in El Salvador. And it does have a presence in Wheaton - there was an incredibly brutal murder in a park in 2017 - but local law enforcement says this sort of crime is rare.

In 2018, there were no gang-related homicides in the county, according to Captain Roland Smith, director of the special investigations division at the Montgomery County Police.

"They [gangs] often prey on law-abiding people in the Latino community, especially the vulnerable. And the victims are often fearful of law enforcement, so that is our biggest challenge," Captain Smith told the BBC. "We are doing a lot of community outreach so people trust us."

Salvadoran residents in Wheaton say they last thing they want is for violence to follow them.

"A few people destroy our reputation," says Mr Solis. "People are coming from El Salvador to escape gangs. We want them caught. We should be working to find them."

What is temporary protected status - and why is El Salvador losing it?

- Published12 November 2019

- Published9 July 2024

- Published22 November 2017