Who controls Canada's indigenous lands?

- Published

The courts in Canada are grappling with a decision central to the relationship between Canadian and traditional indigenous laws.

The dispute involves the construction of a multi-billion dollar gas pipeline in the province of British Columbia.

It's a project which has exposed a rift between elected and hereditary chiefs of the Wet'suwet'en people, who disagree about whether to allow the pipeline to be built through traditional lands.

The elected councils have jurisdiction within the boundaries of the reserves to administer federal government legislation, but not the wider traditional territory which the pipeline would pass through.

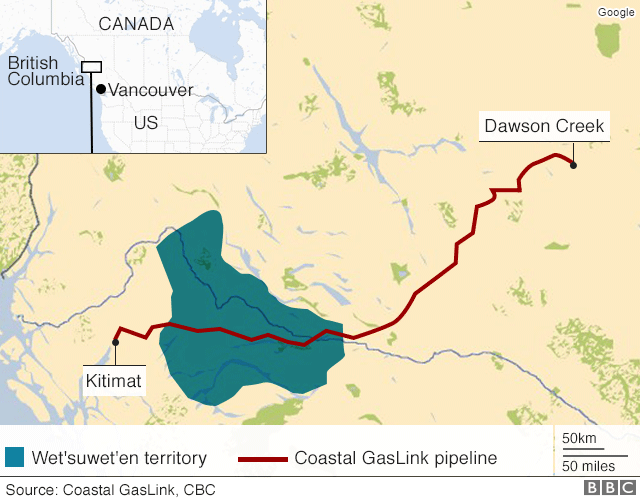

The hereditary chiefs of the Wet'suwet'en nation are stewards and protecters of 22,000 square km (13,670 square miles) of traditional territory, outside the reserves.

They are concerned about the impact of the project on their land and natural resources.

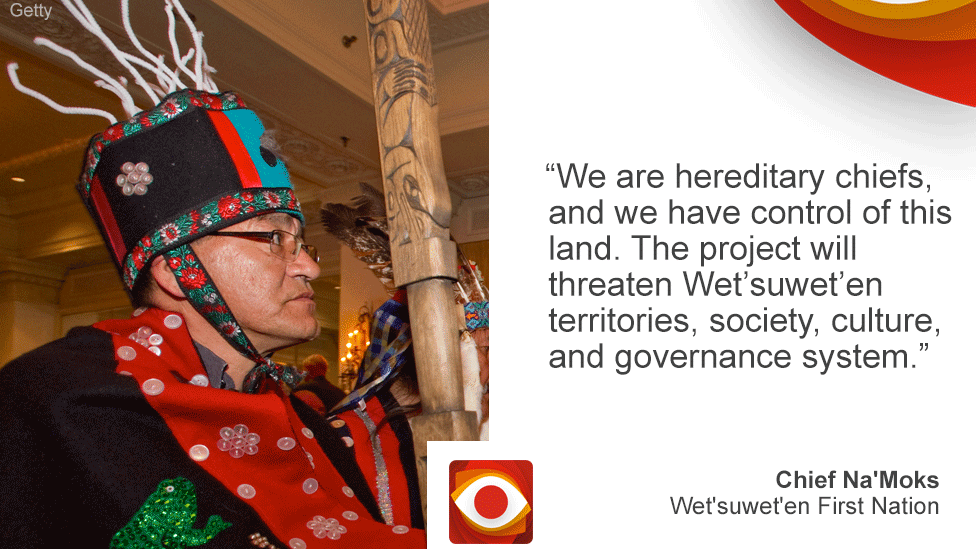

Hereditary Chief Na'Moks of the Tsayu clan, which is part of the Wet'suwet'en people, told the BBC: "You always have to put the environment first."

So what's behind the dispute, and who have the courts favoured?

The pipeline

The proposed pipeline would carry gas to the port of Kitimat from the interior of British Columbia, a journey of 670 km (420 miles), passing partly through indigenous lands.

The construction company Coastal GasLink has reached deals with elected indigenous councils along the route.

Protesters in Vancouver have been trying to get the project stopped

This involved permission to build the pipeline in return for local jobs and investment in the area.

Coastal GasLink says it also consulted the hereditary leaders.

But the chiefs say that did not happen, and that they did not give their approval because of environmental concerns.

Suzanne Wilton, a communications adviser for the company, told the BBC: "Coastal GasLink initiated consultation with the Office of the Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chiefs in June 2012 by providing formal notification of the proposed project.

"Since then, Coastal GasLink has engaged in a wide range of consultation activities with Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chiefs."

Chief Na'Moks responded: "That is their statement...we ensured that we stated at any meetings that these meetings cannot be misconstrued as 'consultation'."

Protests by groups supporting the hereditary leaders' decision have followed near the proposed construction site, and across Canada.

In December, the Supreme Court in British Columbia issued an injunction so that construction could go ahead, and protesters were ordered to remove barriers from access roads.

Police arrived to break up the barriers and remove the protesters, 14 of whom were arrested.

But this provincial Supreme Court ruling was only temporary, and it will shortly make a final decision on the case.

Who speaks for indigenous peoples?

At its heart, this is a dispute about who represents and speaks for Canada's indigenous communities.

Responding to a question at a recent town hall meeting, external, Canada's prime minister Justin Trudeau highlighted the problem of dealing with two distinct groups of indigenous representatives.

"It is not for the federal government to decide who speaks for you. That's not my job," he said.

Hereditary chiefs are chosen by elders and clan members.

The elected indigenous councils were set up by the federal government under the Indian Act of 1876, which defined "Indian" status in Canada, and were designed as a means to assimilate indigenous people.

As such, the elected councils remain a controversial legacy of the past.

A protest camp on a road near the pipeline construction project

"Canada has a long and terrible history in regards to indigenous people," said Justin Trudeau at the same town hall meeting.

"We have not treated indigenous peoples as partners and stewards of this land."

The Indian Act does not recognise hereditary indigenous chiefs, although they do often serve on elected councils, and the two groups work together on community-wide projects.

"We are hereditary chiefs, external," Chief Na'Moks told local media recently in British Columbia, and, referring to the route through which the pipeline would pass, he said "we have control of this land."

"What's called the hereditary system is the historic legal and political and economic system of the Wet'suwet'ens, which was in place for thousands and thousands of years before Europeans came to what became Canada," says Val Napoleon at the University of Victoria in British Columbia.

The decision

A federal Supreme Court ruling in 1997, external gave indigenous people title over their own traditional lands which had not been ceded to the government.

This gave hope to First Nation communities across Canada which had been campaigning to protect their lands, external from developers.

Tensions have remained in some areas over precisely which indigenous representatives have these rights in Canada.

It's a complex issue as indigenous leadership structures vary across the country.

But the forthcoming ruling by the Supreme Court of British Columbia will have important implications for the future of the Coastal GasLink pipeline through Wet'suwet'en territory.

- Published16 May 2018