Polar vortex: A guide to surviving extreme cold

- Published

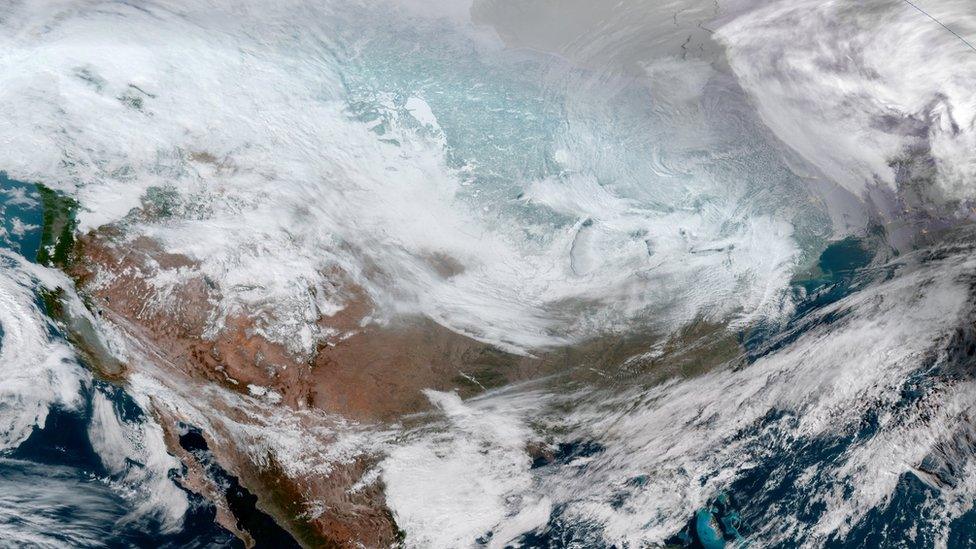

States of emergency have been declared in a number of US states due to the vortex

In the bitter cold winter months, being outside during plunging temperatures can pose a threat to health and safety - and can even be deadly.

Dangerous cold snaps are not uncommon for parts of North America between December and February, affecting millions of people from the Canadian prairies all the way down to the US Midwest and New England.

So what risks does extreme cold pose, and how can you avoid them?

Early signs

There are often two main dangers that people will speak about - hypothermia, in which your body shuts down after reaching an abnormally low temperature, and frostbite, an injury to the body caused by freezing.

The latter is most common on extremities such as fingers and toes, but can affect eyelashes too.

"Frost bite is deep tissue damage, so you freeze all your flesh," says Mike Dinn of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), "and effectively those digits, toes just die and the only recourse is medical intervention."

The time for action, the extreme weather expert says, is at an earlier stage called frostnip before the transition into frostbite.

"It's the precursor to frostbite, and absolutely the point you need to intervene," Mr Dinn explains.

How to keep warm? Tips from cold countries

Frostnip can happen in a matter of a few minutes, turning your skin white and waxy. Common areas are on your hands and cheeks, which you may not see yourself, so it is important to have someone check you, and for you to check them.

"Get out of the cold, or put a hand or even a glove over the area to stop the exposure and bring back the pinkness to the skin," advises the operations manager for BAS.

The damage can be reversed at this point, but Mr Dinn points out you can still lose some of the surface layers of the skin.

Preparation and planning

The best way to avoid risk is to stay indoors, with plentiful stocks of food, water and medicine. Taps can be kept open at a drip to stop pipes freezing. Pets can be brought inside.

When it's not possible to stay inside, you have to plan and prepare to limit exposure, and give extra thought to your hands, head and feet.

Mittens are better for warmth than gloves, while scarves or balaclavas are best for keeping the cold off the face and hats are essential to reducing heat loss.

When you do get cold, get your hands into your armpits or retreat to shelter.

Goggles and glasses can help keep the temperature around the eyes stable

"People don't think about leg cover - walking in jeans in -30 degrees won't get you frostbite, but you might get hypothermia and into trouble quickly," says Mr Dinn, who has over three decades of expedition experience.

Insulating trousers, ski trousers or even wearing pyjamas under your trousers will give that added layer of protection.

However, Mr Dinn cautions: "You need to think of practical footwear, not just insulated footwear but you need to think of not constricting circulation with too many socks on."

The expedition expert strongly advises people who have to go outside to stock their cars with emergency supplies.

Numbness is an early sign for hyperthermia for people outside for long periods like the homeless

"It's always worth having a sleeping bag or blanket in the car," Mr Dinn says. "Carry some warm fluids, have a little bit of food, something to give you energy and a shovel to dig you out of remote roads."

For those who do not have chains for their tyres, hessian sacks or a cloth bag can help with creating traction on the road.

Know your limits

"If people are outside for a long time, they don't notice the transitional period between frostnip and frostbite," warns the expedition expert.

"Even if you have to work outside, you need to go back inside regularly, take warm sugary drinks and snacks into your system, and exercise to keep your blood circulation and body temperature up."

He warns inactivity for any length of time, for example as a result of a car accident, can lead to considerable risk.

Stock your car with supplies to get you going and keep you warm while you call for help

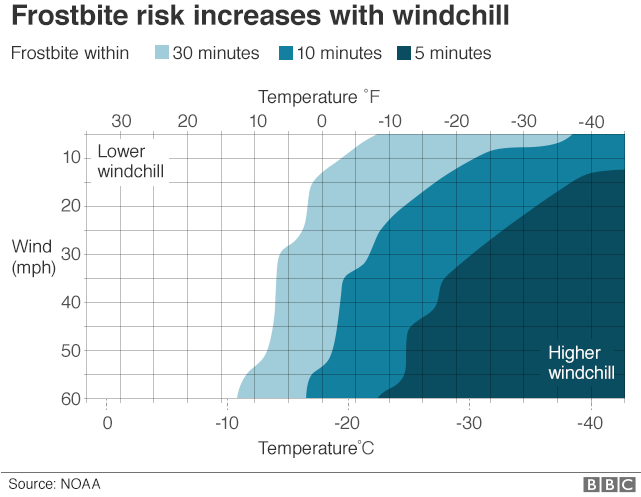

"Stay in the car, out of the wind, because wind chill exacerbates the whole process," Mr Dinn says.

He warns against people making the mistake of thinking they can walk to a nearby town or petrol station for help.

"That's exactly the sort of situation people don't gauge properly, and then you can rapidly lose core body temperature and succumb to hypothermia."

The expedition expert says that, in extreme cases, people may lose their sense of awareness and discard layers because they think they are warm, when actually they are not.

"It only takes one slip up to lead to permanent injury," Mr Dinn says. "But if a person goes about their daily affairs carefully and prepared, you should be fine."

So what actually is a polar vortex...?

Related topics

- Published7 February 2023

- Published31 January 2019

- Published1 March 2018