Robert Mueller: America's most mysterious public figure

- Published

He seldom gives interviews and is rarely seen in public. Yet Robert Mueller, the man who led the investigation into alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US election, is one of the most talked about people in America.

His critics accuse him of spearheading a plot to bring down the president. His supporters say he is a tireless public servant who fought to uncover the truth. But through all the noise he has continued to shun the spotlight.

So who is the man behind the headlines?

FBI Agent Lauren C Anderson was investigating a murder in Libreville, the capital of Gabon, when she received an urgent phone call. The voice on the other end told her that Robert Mueller, who had been appointed FBI director two years earlier in 2001, was trying to get hold of her.

"It surprised the heck out of me," she tells the BBC. "I'm thinking, what could possibly be going on here that he needs to know about?"

A few weeks earlier she had been on a bus in Paris when a man suffered a heart attack. He later died, but she jumped over several rows of seats to give him CPR and, when the medics arrived, consoled his wife on a nearby street corner.

In Gabon, she put the phone to her ear, apprehensively, and heard Mr Mueller's voice.

"I heard that you worked to save somebody's life," he said. "Thank you."

It's a memory that Ms Anderson says reveals something significant about his character.

"He took the time out of his day, at a moment when there was utter chaos happening in the world, to talk to me and make that phone call.

"He takes seriously when people do the right thing. That's what matters to him."

Born into a wealthy family in Manhattan in 1944, Robert Swan Mueller III was raised in Princeton, New Jersey. He was sent to the exclusive St Paul's boarding school in New Hampshire, where his strong moral values, as recalled by Ms Anderson, were quickly noticed by his peers.

"He was an exceptionally serious young man," recalls Maxwell King, who was a classmate of his for five years at St Paul's. "He was straight down the line - very purposeful and very dedicated."

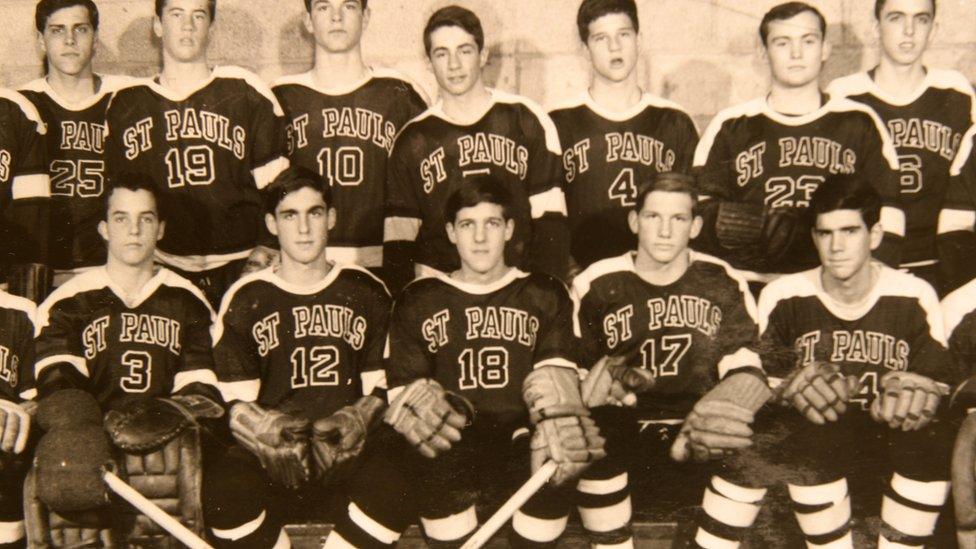

A 1962 image of Mueller's school hockey team in which he wears number 12 and John Kerry, former Secretary of State, wears number 18

He remembers one incident, outside a snack shop in the school, where Mr Mueller showed an early indication of his developing principles.

"Boarding school kids can be very sarcastic," Mr King explains. "We were making fun of somebody and I remember Bob [Mueller] just getting up and leaving, and making clear that he didn't like it.

"He sort of shook his head and left."

This deep-rooted sense of right and wrong is something that a number of people who know Mr Mueller are keen to point out. Phrases like "law and order man" and "straight arrow" routinely crop up i their descriptions of him.

But Mr King says that Mr Mueller's unwillingness to join in with the teasing did little to dent his popularity, which was in large part a result of his sporting prowess.

"He was an exceptional soccer, hockey, and lacrosse player," he says. "I think he was the captain of each one of those three teams.

"He was very much a team player and I think everyone really respected the fact that there was no showboating. It's very similar to his character today - he was just a very straightforward kind of person."

Mr King is also keen to stress the importance the school placed on pursuing public service.

"A lot of us responded to that and wanted to lead lives of service. In Bob's case... we saw that he was dedicated to the school and to athletics, and a lot of us expected that he would do something in public service when he grew up."

Their expectations were met when, after studying politics at Princeton University, Mr Mueller joined the Marines and was sent to Vietnam in 1968.

"It was a time when few people that came from the privileged backgrounds that we came from volunteered to go," Mr King says. "It's an indication of Bob's dedication."

Robert Mueller served as a lieutenant in the Marines during the Vietnam War

In a rare interview in 2002, external, Mr Mueller explained his decision.

"One of the reasons I went into the Marine Corps was because we lost a very good friend, a Marine in Vietnam, who was a year ahead of me at Princeton," he said.

"There were a number of us who felt we should follow his example."

As a lieutenant, Mr Mueller led a platoon of troops, was wounded twice in battle, and was awarded numerous commendations including the Bronze Star for bravery.

"Second Lieutenant Mueller fearlessly moved from one position to another with complete disregard for his own safety," his citation for the award reads.

After returning from the war he went to the University of Virginia, where he studied law and graduated in 1973.

A series of legal jobs followed, first in San Francisco and then in Boston, where he worked as a prosecutor and investigated major crimes such as terrorism and international money laundering. In 1990, he joined the Department of Justice before making what some say was a surprising career move.

"He could have gone from [the justice department] to spend the rest of his life making money at a law firm," says Tim Weiner, author of Enemies: A History of the FBI.

"But instead he became a prosecutor in the Washington DC criminal justice system, which is really kind of an entry-level position.

"He felt a moral obligation to fight crime in Washington, which was in the midst of a murder epidemic driven in part by drug wars."

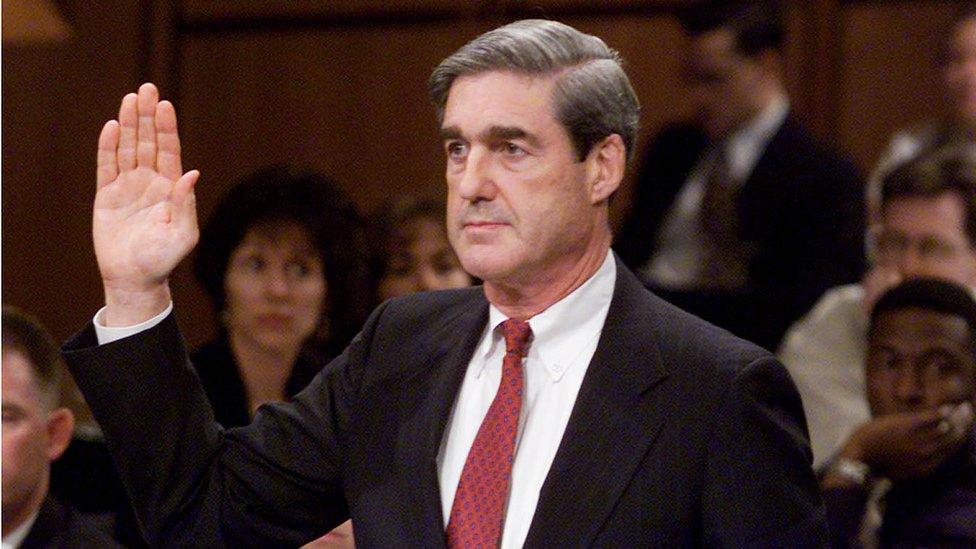

Robert Mueller was unanimously confirmed as FBI director in 2001

In August 2001, Mr Mueller, who most pundits viewed as the clear favourite for the position, was unanimously confirmed as FBI director by the Senate. He was sworn in on 4 September, and arrived at the FBI's headquarters in Washington, DC with a solid reputation forged during his time working as a prosecutor in the city.

But exactly one week after he stepped through the door, the 9/11 terror attacks, in which nearly 3,000 people died, transformed his role forever.

"You can imagine what his second week of work was like," Weiner says. "The FBI that he took over was a deeply troubled institution... it was 95% white men and it did not serve well in its primary function, which is intelligence.

"What Robert Mueller did during his 12 years as director was to make the FBI a 21st Century service and to make it an intelligence service under law."

Ali Soufan, a former FBI agent who worked with Mr Mueller on counterterrorism after 9/11, agrees.

"He was able to effectively reorganise the FBI from its historical law enforcement focus to an intelligence-driven organisation," he says.

But his drive to modernise the bureau - which had technology so outdated that its agents could not even email files to one another - ruffled feathers.

"He was compelled because of 9/11 to bring about dramatic change in the FBI, and I can tell you that trying to bring about that change was very tough," says Lauren C Anderson.

"His decisions garnered him a large percentage of agents who thought he was damaging the FBI."

Ms Anderson adds that the director also frustrated some staff with his unrelenting demand for detail.

"It used to drive people crazy sometimes," she says. "It was not uncommon for him to request very specific details in a briefing - details that some managers considered minutiae. Then they would feel embarrassed and annoyed if they didn't have them."

The 9/11 terror attacks happened just one week into Robert Mueller's tenure as FBI director

Mr Mueller was also criticised for loosening surveillance methods in the wake of 9/11, says Douglas Charles, a professor of US history at Penn State University who specialises in the FBI.

But he points out that in 2004, when President George W Bush ordered the National Security Agency (NSA) to spy on American citizens as a counterterrorism measure, Mr Mueller threatened to resign - which led the president eventually to back down.

"He was extremely vigilant about the danger that the US could lose its civil liberties in fighting the war on terror," says Tim Weiner, who spent some time with Mr Mueller in Mexico City shortly before the 2016 election.

So what kind of man did he meet?

"I saw a man who is outwardly very formal, he always wears a button-down shirt, he always wears a dark suit, he dresses as if it were 1956 and Frank Sinatra is on the radio and Eisenhower is in the White House," he says.

"But beneath that formal exterior is a highly intelligent, highly personable, and intensely focused mind."

What does it take to impeach a president?

Much has been made of Mr Mueller's quiet, low-key, approach to leading the Russia investigation since he was appointed special counsel in May 2017.

Until summoned to testify before Congress, Mr Mueller appeared once briefly to reaffirm the conclusions of his 448-page report on Russian interference in the 2016 US election.

At the time, the special counsel insisted that "the report is my testimony", adding that he did not believe it was "appropriate to speak further" about the investigation and that he would not provide any information that was not in his team's report.

"There is a kind of virtue to being quiet," says Julian Zelizer, a professor of history and public affairs at Mr Mueller's alma mater, Princeton.

"Everyone is loud in this day and age, including the president, everyone is always saying something.

"By being quiet it just adds to the mystique."

- Published24 July 2019

- Published25 March 2019

- Published24 July 2019

- Published24 July 2019