El Chapo guilty: Will his jailing change anything?

- Published

El Chapo trial: Five facts about Mexican drug lord Joaquín Guzmán

The trial and conviction of the notorious Joaquín Guzmán Loera, also known as El Chapo, told us much about the man, the multi-billion drugs trade and the attempts to stop it.

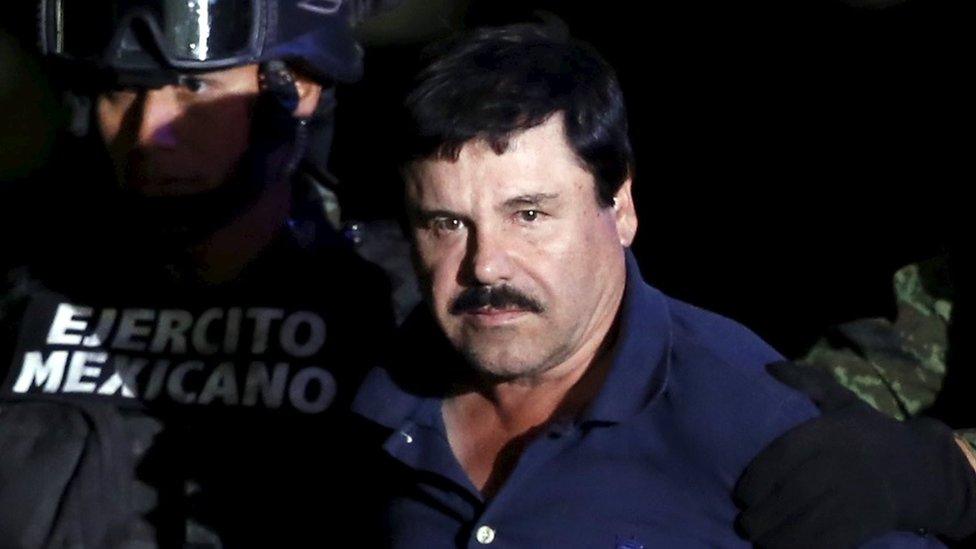

Guzmán, the notorious Mexican drug-cartel leader, has a nervous tic.

He tugs at his right lapel. On difficult days in the courtroom, such as when his ex-mistress testified, he pulled at his jacket more than usual.

He stood trial in New York for drug trafficking charges after successfully evading US and Mexican authorities for years and escaping from prison in Mexico on two occasions.

Other times during the trial, he glanced around the room in a furtive manner. He is known for tunnelling his way to freedom, and people in the room said jokingly that he was looking for an escape route.

Shortly before the jury began their deliberations, Guzmán stopped searching for a way out. He listened intently to the judge. The man who had once overseen the Sinaloa cartel, an enterprise fuelled by cocaine, violence and terror, looked uneasy.

Now he has been found guilty of all 10 criminal counts related to drug trafficking. He faces life in prison, and officials say that most likely he will be taken to a federal supermax in Colorado.

Guzmán was legendary for the tunnels he used to transport drugs under the US-Mexico border as well as to flee prison and escape from authorities. But no-one has ever escaped from the supermax, a place that a warden once described as "a clean version of hell". Chances are Guzmán will die there.

From a business perspective, he'd had a good run. He made $14bn (£11bn) over the course of his career, according to prosecutors.

He trafficked in cocaine, heroin, marijuana and other drugs, explained a US assistant attorney, and he oversaw a network of dealers, kidnappers and "henchmen", a team of assassins on his payroll.

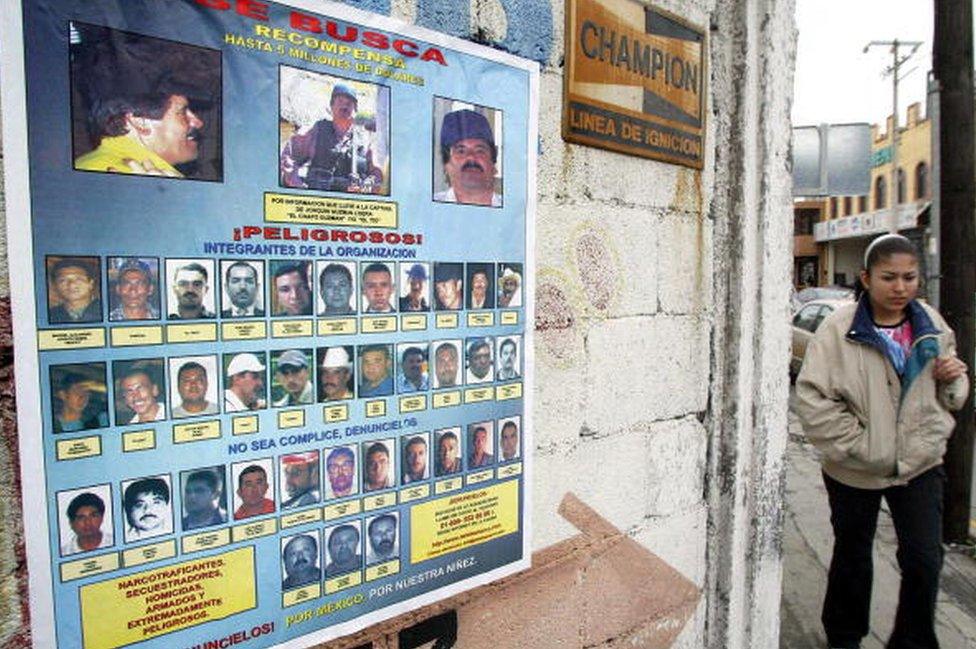

A wanted poster in Monterrey, Mexico features El Chapo at the top

Two years ago, Guzmán was extradited to the US. His three-month trial in a New York courtroom featured more than 50 government witnesses, including men and women who had pursued him for years as well as former cartel associates who decided to testify against him in the hope that they would receive lighter sentences.

The government's first witness, Carlos Salazar, a retired customs agent, says he has seen up close the violence that Guzmán and his cartel members inflict on people.

Salazar had "butterflies" in his stomach when he walked into the courtroom and testified about a tunnel in Arizona that he had found, one that Guzmán used for hauling bricks of cocaine underneath the US-Mexico border.

Still, Salazar says: "I did make it a point to look in his direction. I made eye contact."

Individuals such as Salazar and Brennan, who work or have worked in law enforcement but were not involved in the prosecution, still see the trial as vindication. "It's rewarding to see that at the highest level of narcotics distribution, someone would be held accountable," says New York City's special narcotics prosecutor, Bridget Brennan. "There's satisfaction in that."

"He wreaked havoc in the US for many, many years," says Michael McGowan, a former FBI undercover agent and the author of Ghost, a book that describes one of the bureau's investigations of Guzmán. "It's time to face the music."

Prosecutor Bridget Brennan says Guzmán's methods were "wily"

Washington officials were paying attention: Matthew Whitaker, the acting US attorney general, was in the courtroom one day, shaking hands with prosecutors. The announcement of the verdict was a "proud day" for them, says Mark Feierstein, a former senior director for Western Hemisphere affairs on the national security council. But he warns: "We're not going to win the drug war by prosecuting El Chapo."

The US spends more than $47bn (£36bn) every year in the fight against illicit drugs, according to the Drug Policy Alliance, external, a non-profit organisation based in New York. Yet despite the efforts to arrest drug makers, dealers and kingpins, the problem remains daunting. In 2017, 72,000 people died from accidental drug overdoses in the US.

Some analysts say that the jury's verdict in the trial will lead to more violence because traffickers will now fight over territory in a post-Chapo narco-land. "This is a corporate struggle," says Dennis Jay Kenney, a former police sergeant who is now a professor at John Jay College in New York. While the cartel members jostle for power, he says: "There'll be more bodies hanging from bridges in Mexico."

The trial could have been held in Chicago, Miami or any number of other US cities, since Guzmán and members of his cartel had operated across the nation.

But officials in the US attorney general's office decided the New York prosecutors had the best chance of winning the case.

Homeland security vans were parked outside the courthouse each morning during the trial. A Geiger counter was located in the lobby, sitting on a table next to a gas mask.

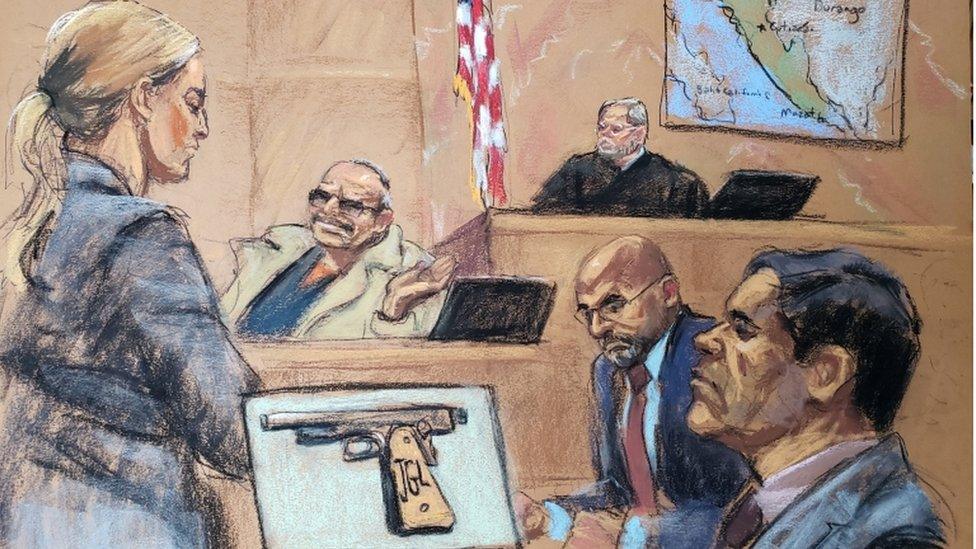

Mexican police display drugs and weapons seized from the Sinaloa cartel

"Cagey, wily", says narcotics prosecutor Bridget Brennan, describing Guzmán: "Really bold".

The trial showed Guzmán's human side. He and Mariel Colón Miró, a member of his legal team and a recent law-school graduate, sat next to each other in the courtroom and passed notes back and forth. "It's been a client-attorney relationship and very professional," she says. "But there's always room for laughs."

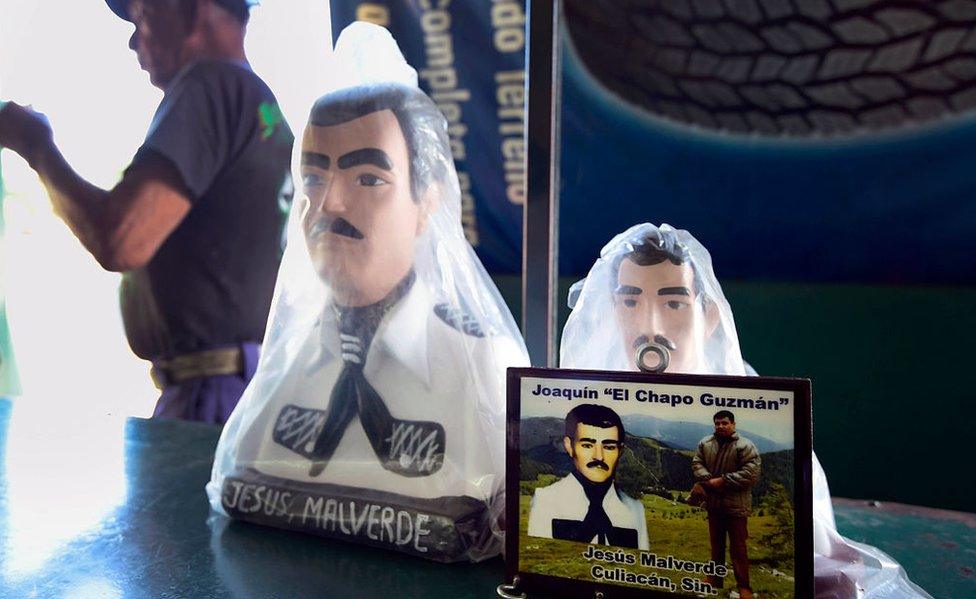

In Mexico, ballads known as "narcocorridos" are devoted to him, and a 2014 poll, external suggested most people believed he was more powerful than the Mexican government.

People in Culiacán, a city in the Mexican municipality where Guzmán grew up, adore him. "A magnificent person," a bookseller told Reuters: "It's such a pity he won't be able to escape from the United States."

Guzmán is famous in the US too. At a bagel shop a couple miles from the courthouse, the El Chapo is made with jalapeño cream cheese (cartel members used to pack cocaine into jalapeño cans). In a Netflix series Narcos: Mexico, he is portrayed as a cunning, violent man.

Supporters in his home state rallied for his release after his 2014 arrest

When Guzmán walked into the courtroom each morning, a hush would fall. When a defence lawyer hugged him, people gasped.

Guzmán's wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro, 29, sat on the other side of the courtroom, wearing a watch with diamonds, the same kind of jewels that were once affixed, according to a government witness, to her husband's pistol.

As the prosecutors showed, Guzmán used violence to maintain control over the illegal drug market and reaped its rewards, bestowing riches on his family.

"I saw him wave at his wife, and at first I thought: 'How cute,'" says Malcolm Beith, who has written a book about Guzmán.

A moment later, his feelings changed: "I almost threw up in my mouth. I had this visceral reaction, knowing what he's responsible for."

Emma Coronel Aispuro watched the courtroom proceedings from one of the benches

For some, that was the attraction.

"Isn't it worth it to see a person who's been called the most dangerous man in the world?" says Clarissa McNair, a private detective who lives in Queens, while she ate a chocolate chip cookie during a courtroom break. "He looks small and inconsequential," she says, adding: "His looks are very deceptive."

A cosmetics sales representative says she wanted to see the "telenovela", comparing Guzmán's trial to a Spanish-language serialised drama. Others in the courtroom acted like they were at a matinee -one afternoon a couple sat in the second row, listening to the proceedings, and cuddled.

It was a grisly movie with a high body count.

Assistant US Attorney Andrea Goldbarg told jurors about an evening in the mountains of Sinaloa when Guzmán "levelled his rifle" at a wounded man and "cursed him and then shot him". She said: "The cartel's engines were violence and corruption."

Trolleys of documents, stuffed into accordion folders, were parked next to her table in the courtroom - the "mountain of evidence" that Goldbarg described in her closing argument. Towards the end of the trial, pillows were available for exhausted members of the legal team.

An El Chapo plaque in a chapel in Culiacan, Sinaloa - his home state

Goldbarg said that the evidence all pointed to one thing - Guzmán called the shots.

"He's the one deciding who lives and who dies."

During her closing argument, she replayed a video, external that showed Guzmán interrogating a man who was hog-tied and bound to a pole - while a rooster crowed in the background. The video demonstrated, according to Goldbarg, that Guzmán not only oversaw the cartel, he personally inflicted the violence.

Later one of Guzmán's lawyers paced around the courtroom and tried to portray Guzmán as a victim of the US authorities, saying he was not the cartel leader and yet had been "hunted like an animal" for years - and that the government's witnesses were criminals and should not be trusted.

A government lawyer said it would be great to "call angels as witnesses" but in Guzmán's case it made sense to ask those who knew about the cartel to testify in court about his criminal activities.

One of the witnesses, Guzmán's former mistress Lucero Guadalupe Sánchez López, 29, said that he had told her that he would kill anyone who crossed him - even if they were a member of his own family. "I didn't want for him to mistrust me because I thought he could also hurt me," she said.

In the courtroom, Lucero Guadalupe Sánchez López described her fear of Guzmán

While she was in the witness box, she blinked every few seconds. At one point she began to cry.

The fear that she felt in the courtroom was part of a strategy that Guzmán and his cohorts used to maintain control.

"If you've lived with them, you know what they're capable of," says Robert Mazur, a former federal agent who worked undercover as a money launderer. (His memoir, The Infiltrator, was turned into a Bryan Cranston thriller.) "They wouldn't think for half a second about killing everybody in your family."

Analysts say that the trial, however spectacular, will have little impact on the drug war. "We're trying to stop commerce in a product that is in high demand," says the Cato Institute's Ted Galen Carpenter.

Yet US authorities say the trial nevertheless plays a key role in the fight.

"It's important to hold everyone, and especially those at the very top of the pyramid, accountable for their actions because there's been a tremendous amount of tragedy and death and misery," says narcotics prosecutor Bridget Brennan.

Former agent Michael McGowan agrees that it's important to hold Guzmán accountable but he says he feels no personal animosity towards him.

"He's a professional. We're professionals," says McGowan. "We happened to win the last round."

In the end, the trial helped to shed light on the drug trade and its impact on the nation.

"It's very simple," McGowan says, describing both the trial and his work as an agent. "It's the search for the truth."

Guzmán already knows the truth about his role in the cartel, and towards the end of the day he regained his swagger.

Before the jury began deliberations, he turned to his lawyers and made a fist, a kingpin's salute, and left the room.

- Published4 February 2019

- Published17 July 2019