Behind the legacy of America's blackface

- Published

Protesters rally against Virginia Governor Ralph Northam outside of the governor's mansion

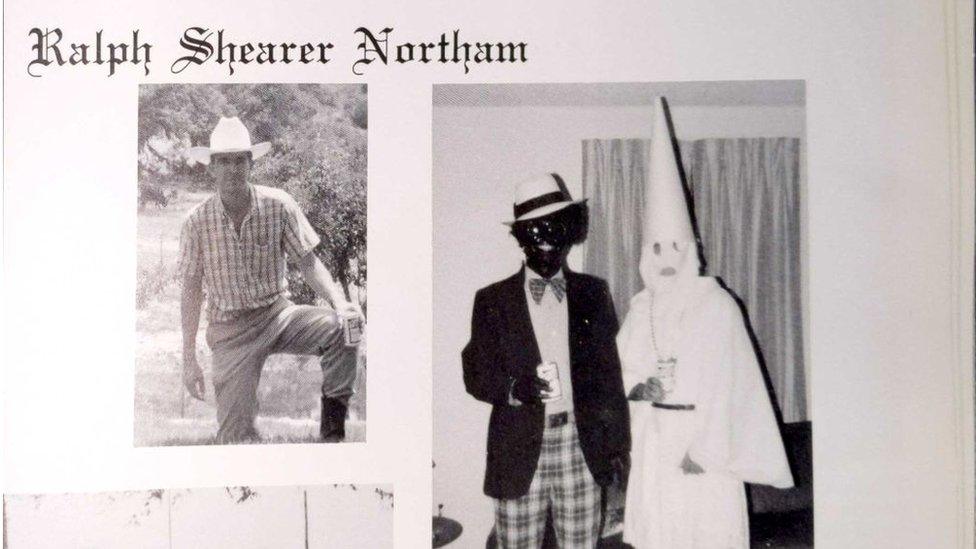

Democratic Governor of Virginia Ralph Northam has refused to resign from office following the emergence of a photo from his 1984 medical school yearbook featuring a white man in blackface alongside another man wearing a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) robe.

On Friday, Mr Northam apologised and claimed that he was one of the two men in the photo, and in a news conference on Saturday denied being either man in the picture, refusing calls to resign.

At the disastrous news conference, the governor also admitted to wearing blackface at another occasion in 1984 when he dressed up as Michael Jackson for a dance contest, strangely boasting about winning the competition because he could moonwalk.

He then lost the support of Virginia's senators, Tim Kaine and Mark Warner, as well as Virginia's first and only African-American governor, L Douglas Wilder.

All three men plus a growing number of politicians on both sides of the aisle have called for his resignation, yet Mr Northam appears intent to try to weather this storm.

Mr Northam's blackface controversy is America's third major blackface scandal in a matter of months.

Ralph Northam's page in the 1984 yearbook of Eastern Virginia Medical School

In January, journalist Megyn Kelly formally left NBC after defending blackface on her show in October.

And also in January, Florida's secretary of state Michael Ertel resigned after photos emerged of him wearing blackface when he dressed up as a Hurricane Katrina victim for a costume party.

Blackface has a long and troubling history in the United States, so one must wonder why so many prominent Americans are unaware of or indifferent to the harm it causes.

Tensions surrounding blackface stem from the fact that America remains unwilling to educate people about the history of blackface, according to Howard University professor Greg Carr.

"It is not taught at all in school. Even in the most basic sense," says Prof Carr. "If it were taught, it would become problematic in America because the vestiges of blackface minstrelsy are a deep part of American culture."

The practice of blackface grew in popularity in the 1830s as white actors would darken their faces with a mixture of charcoal, grease, and soot and perform as caricatures of African-Americans.

The purpose of these performances was to demean and dehumanise African-Americans, and it should come as no surprise that this minstrel theatre of anti-black propaganda grew in popularity as the call for the abolition of slavery increased.

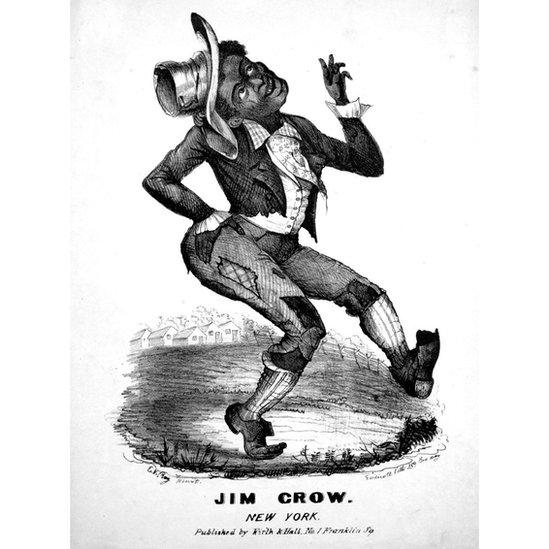

Sheet music cover image of the song 'Jim Crow'

"The purpose of blackface was mocking… and erasing black culture, turning it into a figment of the white imagination for entertainment," says Prof Carr.

"Minstrels began caricaturing black characters they claimed to have seen on plantations dancing and singing. They would dress up in ill-fitting clothes, rags or approximations of tuxedos."

New Yorker Thomas Dartmouth Rice, considered the "father of American minstrelsy", performed under the blackface persona of Jim Crow, and his rendition of Jump Jim Crow was one of the most popular songs in America.

Mr Rice travelled across the US performing as Jim Crow, and his mocking caricature of black manhood and culture would become the new American narrative of black existence.

It became common for Americans to refer to black men as Jim Crow, and the widespread popularity of Mr Rice's song Jump Jim Crow made many foreigners believe it was the national anthem.

Though Mr Rice died in 1860, blackface and Mr Rice's legacy of Jim Crow continued unabated.

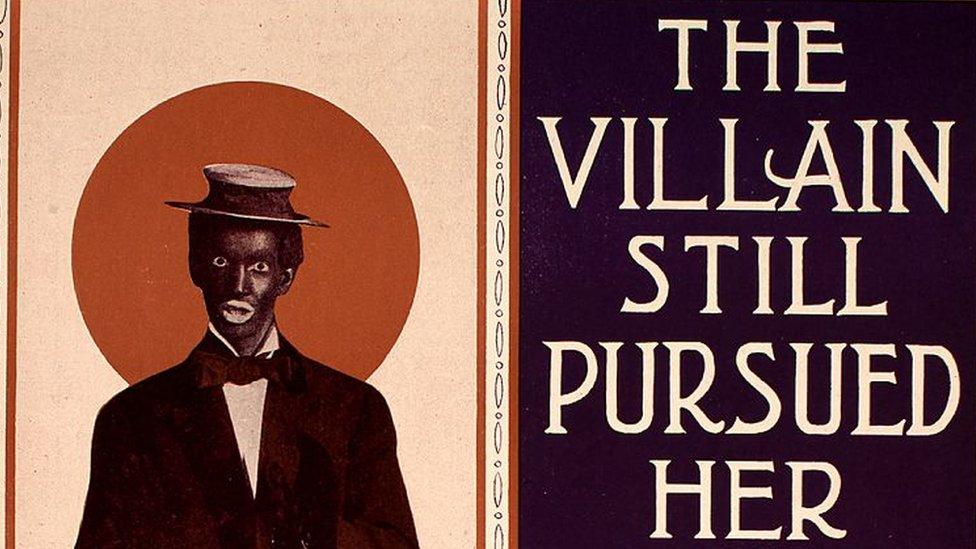

Sheet music depicting white singer and comedian Al Jolson in blackface

When Southerners instituted a series of segregationist laws, poll taxes, and literacy exams with the explicit purpose of returning African-Americans to a life akin to pre-civil war chattel slavery, they named these laws Jim Crow.

And in 1915, when America's first blockbuster movie, DW Griffith's Birth of a Nation, hit theatres, it featured white actors in blackface behaving as savages as they attempted to rape white women.

A group of Klansmen surrounding freed man Gus (played by white actor Walter Long in blackface) in a scene from Birth of Nation

This film not only brought blackface to the big screen, but its heroic depiction of the KKK normalised the white supremacist terrorist organisation.

The KKK became an active part of American politics during the early 20th century.

President Woodrow Wilson screened Birth of a Nation at the White House, and he reportedly lauded the film as "like writing history with lightning."

From the White House and across the nation, anti-black caricatures orchestrated by racist white Americans were considered historical truths, and blackface and minstrelsy remained an oppressive American norm.

In 1929, as cartoons and animation boomed, Walt Disney debuted Mickey Mouse, who was based on vaudevillian minstrel shows, and the first depictions of the famous mouse featured him in blackface.

And while Mickey Mouse soon lost his blackface, the minstrelsy remained.

People from Padstow in Cornwall have been blacking up for an annual parade for 100 years but is that ever OK?

Jim Crow remained the law of the land in South until the civil rights era of the 1960s ended segregation and returned voting rights to African-Americans.

America has only had 50 years since the racist propaganda popularised by blackface has not been the law of the land.

Despite the progress of the 60s, many Americans resisted the change: dehumanising narratives of African-Americans being animalistic and sexualised have remained relatively common in America.

America does not teach this history of blackface in any curriculum known to Prof Carr, and Americans can only learn about this history if they do their own research or take courses in college about African American history.

A Burial Burning of Jim Crow on June 11, 1967

Since the civil rights era and the end of Jim Crow, America has become more diverse and less racist, but some white Americans began wearing blackface to impersonate some of their black heroes.

Mr Northam dressed as Michael Jackson while Kelly referenced blackface as a Halloween costume on her show in October.

Yet as Mr Northam shows, allowing white Americans to wear blackface opens up a Pandora's box of racist propaganda.

In one instance he's "celebrating" Michael Jackson, and in the next he's associated with an image of a white man in blackface smiling next to someone dressed in KKK robes.

It can be nearly impossible to differentiate between white naiveté and malice regarding blackface, but regardless of a non-black person's intent, the impact is detrimental to black Americans.

Blackface, minstrelsy and white Americans mocking black culture have remained a part of US culture that some refuse to address.

Blackface obviously should not have a place in an equitable, non-racist society, but sadly, it has always played a significant role in American life.

Barrett is a writer, journalist and filmmaker focusing on race, culture and politics

- Published11 September 2018

- Published14 August 2017

- Published17 May 2018

- Published10 August 2018