Elizabeth Warren: Can she go all the way to the White House?

- Published

Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren has been a favourite of the progressive left for more than a decade. Can she translate her policy knowledge and popularity with the liberal grassroots into presidential campaign success? In a crowded field, it may not be easy.

"So, I want to tell you a story."

Elizabeth Warren officially launched her campaign for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination the way you might imagine a former Harvard professor would begin. With a history lesson.

The Massachusetts senator told the crowd of several thousand in Saturday's blustery cold about Everett Mill, the site where they had gathered in Lawrence, Massachusetts . Back in 1912, the textile factory was the scene of a labour strike for better pay and working conditions that expanded to include 20,000 workers, mostly women, in the then-bustling industrial town.

The movement that started in Lawrence, she explained, led to government-mandated minimum wage, union rights, weekends off, overtime pay and new safety laws across the US.

"The story of Lawrence is a story about how real change happens in America," Ms Warren said. "It's a story about power - our power - when we fight together."

The extended opening was classic Warren. Erudite, informative and a bit long-winded. A mix of Ivy League intellectualism and blue-collar witticisms drawn from her working-class childhood in Oklahoma.

These days, Lawrence isn't much to look at. Its once-imposing factories are worn and darkened by soot and time. The tall brick smokestacks stand like husks of trees in a long-dead forest. Twenty-nine percent of the town's 80,000 residents live below the poverty line. Opioid drug trafficking and abuse is rampant.

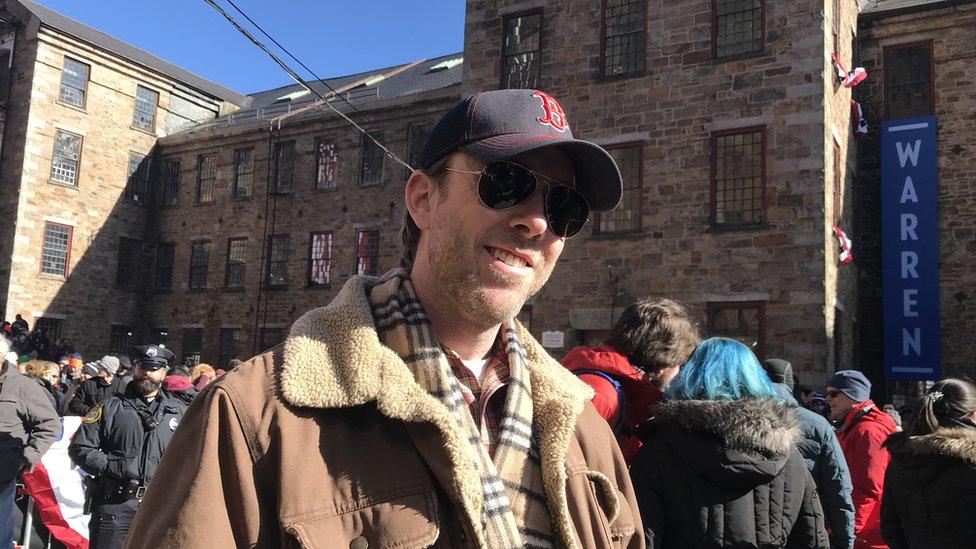

Brian Perry, a Massachusetts bricklayer, says Donald Trump identified America's economic problems - but Elizabeth Warren will fix them

Although Ms Warren didn't cite modern-day Lawrence as a cautionary tale, the backdrop served to illustrate another part of her message - that the current financial structure of America is broken, a victim of rapacious big business and indifferent government. The middle-class, she said, is struggling in a "rigged system that props up the rich and the powerful and kicks dirt on everyone else."

If that sounds a bit familiar, it's perhaps because the problems she identifies are similar to the ones highlighted by Donald Trump in his successful 2016 presidential campaign. Of course, her policy prescriptions are the opposite - and Ms Warren has positioned herself as a frequent critic of the president's. She says government needs to take a more active role in reining in the excesses of capitalism and provide a sturdier safety net for those on society's margins.

"Trump gave people false hope," says Brian Perry, a bricklayer from Weymouth, Massachusetts who came to Lawrence to hear Ms Warren speak. "He said all the right things. He's just unprepared and not interested in fixing them. In fact, he made it worse. She intends to change it, and she's willing to offer real solutions."

The solutions Ms Warren proposed on Sunday include "big, structural change" that addresses the corrupting influence of money in Washington, growing wealth inequality throughout the nation and electoral dysfunction that threatens a free and fair democratic process.

Her centrepiece policy, at least so far, is a 2% tax on the wealth of households worth more than $50m, rising to 3% on portfolios over $1bn. She said it was an "ultra-millionaire tax to make sure rich people start doing their part for the country that helped make them rich".

The progressive champion

It's that the kind of talk that has made Elizabeth Warren a star of the progressive left for more than a decade. She burst onto the national scene following the 2008 economic collapse, championing the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau - a government agency that would serve as a Wall Street watchdog and public advocate. In 2010, following congressional passage of the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, she helped the Obama administration set it up.

Two years later Ms Warren rode that wave of attention to a seat in the US Senate by defeating incumbent Republican Scott Brown, who just two years earlier had won a special election to fill the rest of the late Edward Kennedy's term. A viral video of her explaining taxation and government debt got more than a million views on YouTube.

During her tenure she earned a reputation for her hard-nosed questioning of business executives from her perch on the Senate Finance Committee. She was floated as a possible presidential contender in 2016 and a potent challenger to Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination, but demurred, saying she had no interest in the White House job.

Now that calculus has changed. On New Year's Eve she became the first major Democratic candidate to announce that she was planning a presidential bid. She hit the campaign trail in the key early voting states of Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina, as well as Puerto Rico.

According to Iowa political analyst Pat Rynard, Ms Warren made a big splash in her January visit to his state - an indication that her popularity on the left could translate into votes in 2020.

"It was really eye-opening," he said. "There were huge, enthusiastic crowds who knew her well and really liked her talk about fighting on behalf of the middle class and taking on the big banks."

On Saturday, Ms Warren returned to her home state to formally announce she was running - and how she intended to win.

"There are a lot of people out there with money and power and armies of lobbyists and lawyers," she said. "People who will say it's 'extreme' or 'radical' to demand an America where every family has some economic security and every kid has a real opportunity to succeed.

"I say to them, 'Get ready, because change is coming faster than you think.'"

More on the Democratic 2020 race

White House obstacles

Ms Warren will compete in a crowded primary field - one that already includes four of her fellow senators, four other women and at least a dozen more potential candidates. No candidate will have a smooth path to the Democratic nomination, and the reality is she has some imposing obstacles between her and the prize.

Last Friday the Boston Globe published an editorial, external that highlighted a negative story that has dogged Ms Warren since she first ran for the Senate seven years ago - her past claims of native American heritage. She had previously claimed in interviews, publications and her 1986 Texas state bar application that she had Cherokee Indian heritage - and was once listed by Harvard University as a minority hire.

Ms Warren says she was simply recounting what her parents had told her and she received no benefit from that status. The Globe wasn't satisfied.

"Warren's never been a member of any tribe," the Globe writes. "She's white. Playing loose with the facts about identity is bad within the current political climate of the Democratic Party, where issues of race have come to the fore."

Last year the Massachusetts senator released results of a DNA test that showed some native American blood, but the move did nothing to quash the criticism - and, in fact, led to sharp criticism from tribal leaders.

Could Democratic memories of Hillary Clinton complicate Elizabeth Warren's presidential hopes?

The controversy has also attracted the attention of President Trump, who has frequently mocked Ms Warren with the name "Pocahontas," a reference to the 17th Century daughter of a Powhatan tribal chief captured by English settlers.

On Saturday morning, the Trump campaign issued a press release blasting Ms Warren's "dishonest campaign" as well as criticising her policies, which it said would "kill jobs and crush America's middle class". It was the first time the Trump team has directly attacked a Democratic candidate on their campaign launch day.

Even among Ms Warren's supporters at her Lawrence rally, there was some unease with the controversy - not with the nature of the allegations, but how the senator has responded to the subsequent fallout.

"I think she's probably handled it poorly," says Melissa Saalfield of Concord, Massachusetts. "It's unfortunate because I think it's somewhat derailing her campaign."

Saalfield, a fundraiser for a local hospital, laments that while scandals seem to "roll off" Mr Trump, Ms Warren can't seem to shake this one. And the pressure and scrutiny of the senator will only grow sharper as she gets deeper into the campaign.

"I suspect that there's a larger contingent that are determined to derail her because she poses a threat," Saalfield says.

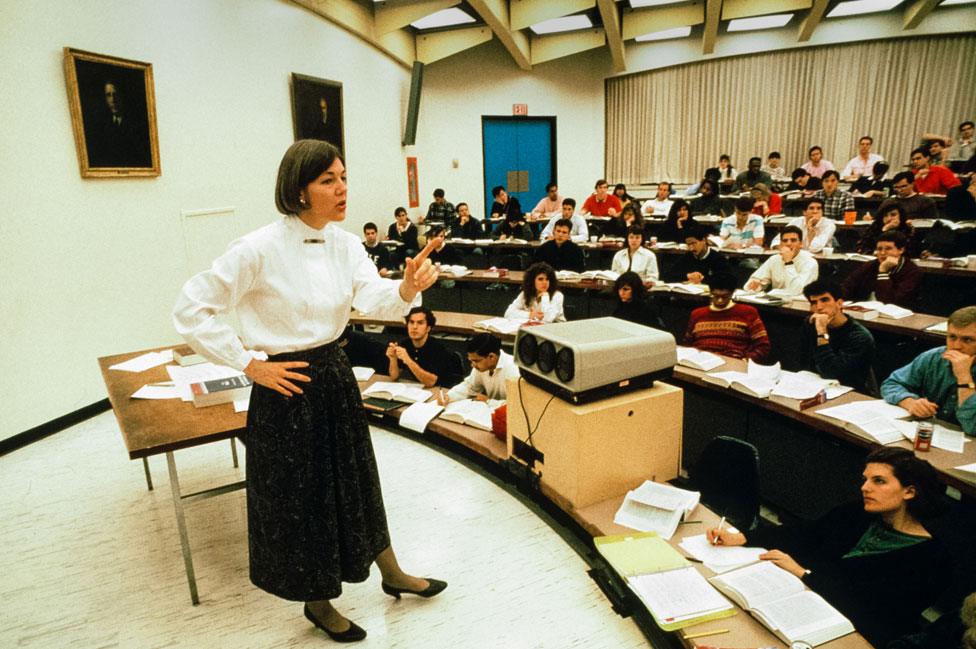

Professor Warren teaching law in the early 1990s

Part of the skittishness among some Democrats when it comes to Ms Warren comes from the memories of the 2016 campaign, when the story about then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's private email server - which was similarly dismissed by many as a passing controversy - bedevilled the Democratic nominee right up until election day.

The similarities between Ms Clinton and Ms Warren as candidates - both white women running in their late 60s, both with policy-heavy campaigns, both relentlessly mocked by Donald Trump - could, fairly or not, be enough to touch raw nerves and give some Democrats pause.

A much-publicised Politico article, external questioned whether the "ghosts" of Ms Clinton's campaign would haunt Ms Warren. The article was criticised as painting both politicians with a sexist brush - but it hinted at a deeper danger to Ms Warren's presidential hopes.

"When women politicians - especially women politicians who embrace a feminist agenda - overtly seek power, many American men, and some American women, react with 'moral outrage,'" writes the Atlantic's Peter Beinart, external.

The Bernie factor

There is another thread that could link Ms Clinton and Ms Warren, and that's the threat to their campaign posed by the candidacy of Bernie Sanders.

It may not at first seem obvious. The Vermont senator ran well to Ms Clinton's left in 2016, offering a big-ticket progressive agenda like universal healthcare, free college education, sweeping environmental regulations and a tax structure to address growing income inequality. In 2019, that sounds a lot like Ms Warren's platform.

There is, however, friction between the philosophical outlooks of the two New England senators. If Mr Sanders, as is expected, enters the race, those differences could lead to a pitched battle for the progressive portion of the Democratic primary vote.

According to Zaid Jilani, a progressive commentator and writing fellow for the University of California Berkeley, Ms Warren is a pragmatist, while Mr Sanders is a political revolutionary.

Friends... and, potentially, rivals

She has hired former Clinton and Obama campaign staffers friendly to the establishment; he is offering a challenge from the outside. She was a registered Republican in the 1990s; he has been a self-proclaimed "Democratic Socialist" since the 1960s. Her policies aim to smooth capitalism's rough edges and create a competitive economic environment; he would prefer government step in and run things.

"When you're president you have limited amount of political capital and time to get things passed," Jilani says. "You prioritise your core beliefs, and her heart is much more about 'can we make markets fair'?"

In an October 2018 essay in the Guardian, external, Jacobin magazine editor Bhaskar Sunkara was even more direct.

"Though Warren is an ally of many progressive causes, the best chance that we have to not just construct some better policy, but reconfigure a generation of American politics lies with Sanders running and capturing both the Democratic primary and the presidency," he writes.

The fight ahead

If Ms Warren can't win over some of the progressive true believers who flocked to Mr Sanders in 2016, a campaign focused on economic inequality and reform could struggle to gain traction. Her ideas may pull the rest of the field to the left, but candidates with clearer constituencies within the Democratic Party could flourish while she stumbles.

Ms Warren is set to give it a shot, however. Iowa's Reynard says the senator is putting together a top-notch campaign operation.

"It's not just some little investment," he says. "This is a team that you build to win."

Elizabeth Warren mauls 'gutless' Wells Fargo boss

Success there, followed by a strong showing in New Hampshire, which neighbours her home state of Massachusetts, could knock enough other candidates out to give her a clearer path in the slew of states that follow.

She's spent more than a year collecting favours and building a campaign network across the US, and early success could position her to cash in on those investments.

"There will be plenty of doubters and cowards and armchair critics" of her campaign, Ms Warren said in Lawrence on Saturday. "But we learned a long time ago that you don't get what you don't fight for. We are in this fight for our lives, for our children, for our planet, for our futures, and we will not turn back."

In just under a year, she'll have a chance to prove the doubters, cowards and critics wrong.