Viewpoint: Why Trump may win his legal fight over border wall

- Published

Other presidents got money for a border barrier - why not Trump?

The latest chapter of Washington dysfunction has culminated in drastic action by the president in order to deliver his key campaign promise. But as his opponents shake their heads and counter-punch through the courts, the historical lessons do not bode well for them, writes Jonathan Turley, professor of constitutional law at George Washington University.

President Donald Trump's declaration of a national emergency to build his long-promised border wall was met with a torrent of condemnations and threats from Democratic critics, including preparation for another heated court fight.

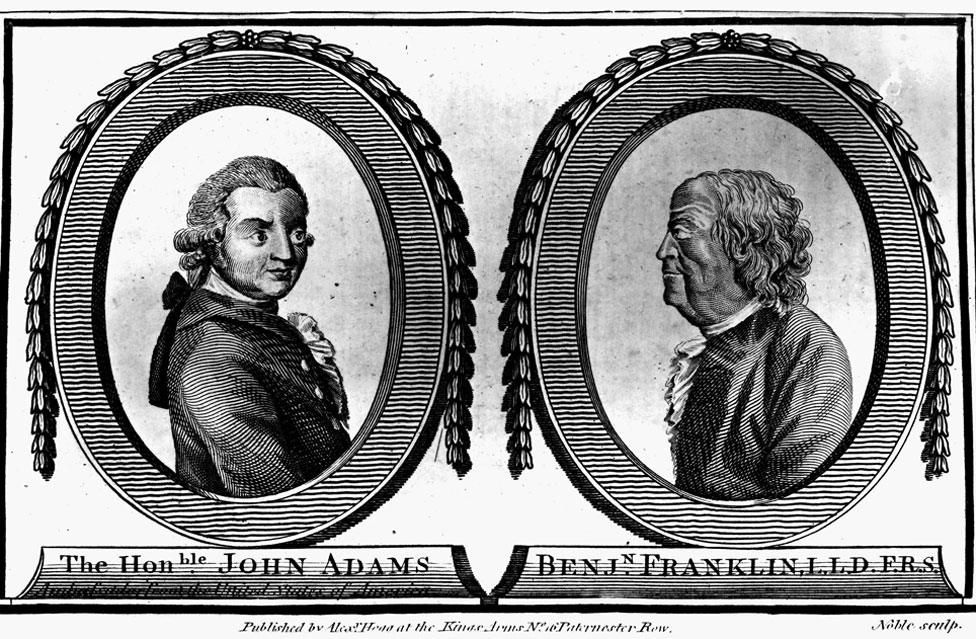

American politics have not been so bitter and divided since Benjamin Franklin and John Adams were forced to share the same bed in 1776.

There is a fundamental incompatibility - if not mutual revulsion - that divides our politics and its focus has fittingly become a debate over a wall.

Does the reality at the border matter?

After securing only part of the funding that he sought, President Trump declared a national emergency along the southern border to allow him to start construction with over $8bn (£6.2bn) of shifted funds to complete his signature campaign promise. For their part, the Democrats are promising immediate court challenges.

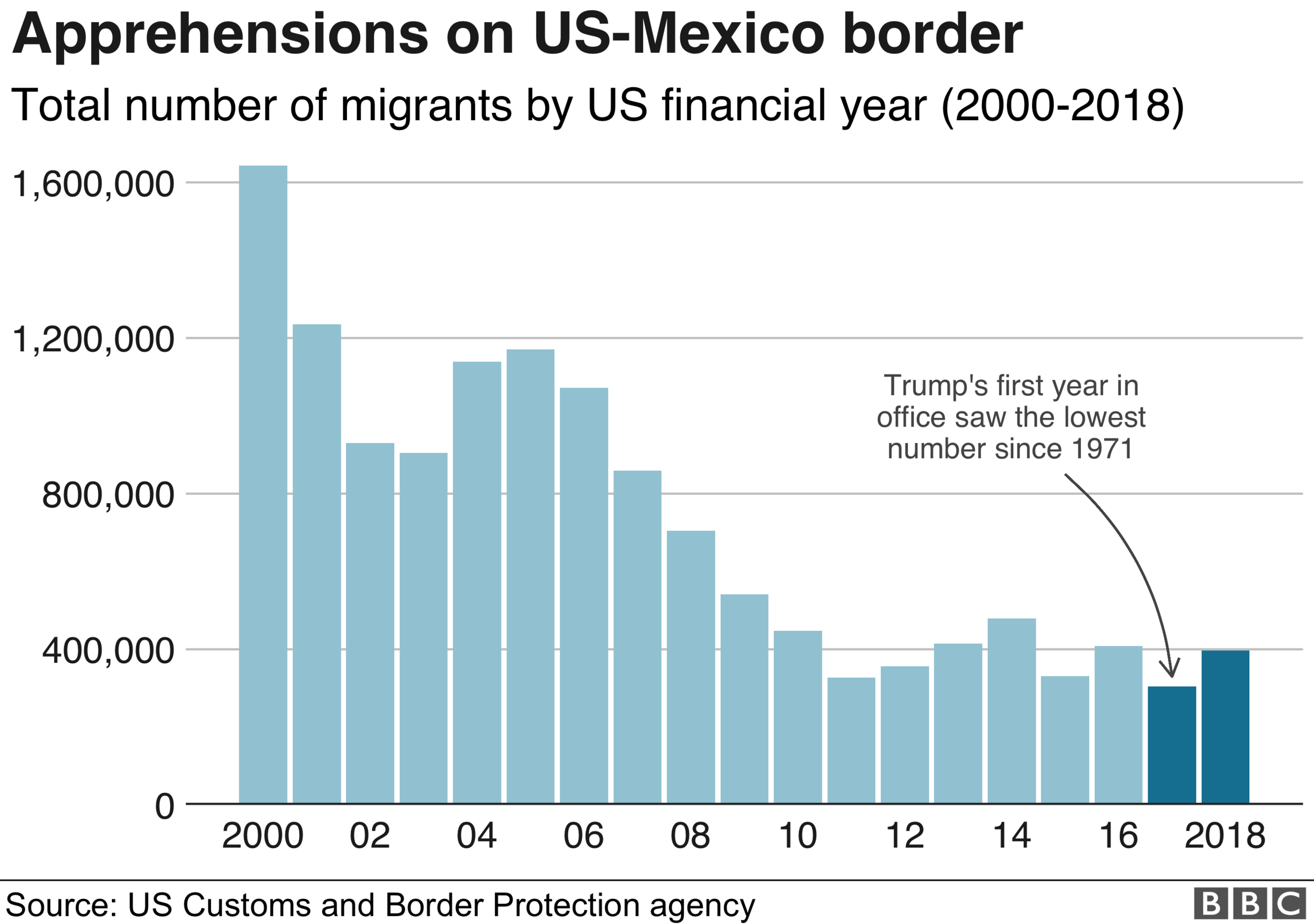

There is little evidence of a true national security emergency on the US border with Mexico. Most illegal immigrants overstay their visas or pass through ports of entry. Moreover, the number of apprehensions are down from 1.6 million in 2000 to roughly 400,000 in each year of Trump's term.

That does not mean that border protection and enhanced enforcement is not warranted. Crossings do remain a serious problem, but few would call this a national emergency.

Yet, President Trump is calling this a national emergency and that may be enough. The reason is not the data but the definition behind a declared emergency.

What is a national emergency?

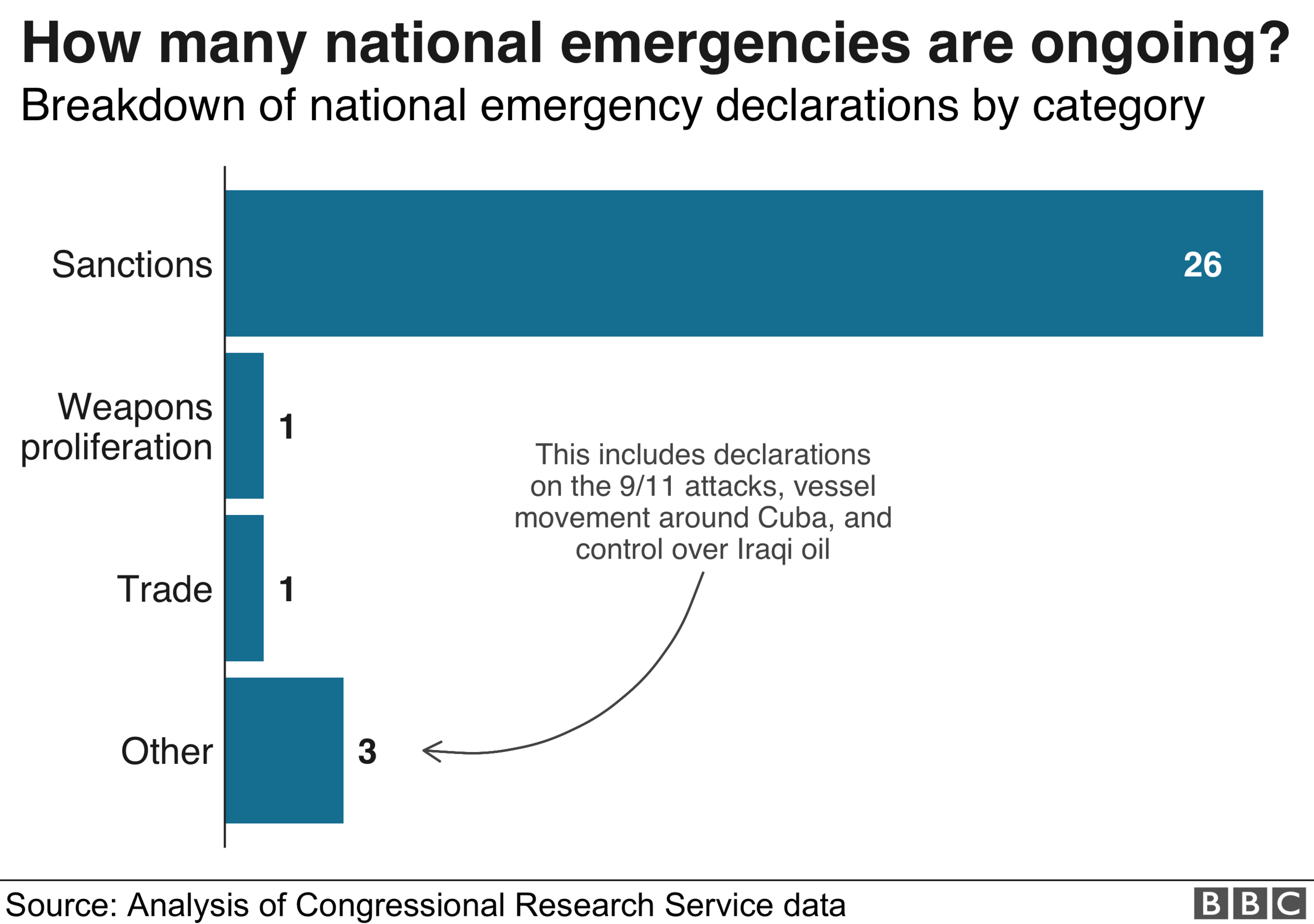

There is no real definition. Under the National Emergencies Act of 1976, Congress simply allowed a president to declare an emergency and to assume extraordinary powers to combat it.

That is the reason why emergencies are so easy to declare and so difficult to end.

While Congress reserved the right to rescind a declaration, it has never done so.

Even if the Democrats secure enough votes in both houses to negate the declaration by a majority vote, it can be vetoed by the president. It would then require a super-majority of two-thirds of both houses to override the veto.

The challenge for the Democrats is getting a federal court to supply the result that they could not secure in their own branch of government. If they are unable to secure a majority of the 535 members which make up both houses of Congress, they are unlikely to change the result with the single vote of an unelected federal judge.

'Haze of Democratic hypocrisy'

There is also a problem for the Democrats in getting a judge to listen to arguments through a thick haze of hypocrisy.

President Trump's assertions of executive authority remain well short of the extremes reached by Barack Obama who openly and repeatedly circumvented Congress.

In one State of the Union address, Mr Obama chastised both houses for refusing to give him changes in immigration laws and other changes. He then declared his intention to get the same results by unilateral executive action.

President Obama with the Libyan ambassador in 2011

That shocking pledge was met with a roar of approval from the Democrats - including Speaker Nancy Pelosi - who celebrated the notion of their own institutional irrelevancy.

In 2011, I represented Democratic and Republican members who challenged the right of President Obama (and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton) to launch the Libyan war without a declaration from Congress.

Mr Obama then proceeded (like Mr Trump) to use loose funds in the executive branch to fund the entire war without an appropriation.

Ms Pelosi and the Democratic leadership enthusiastically supported Obama's circumvention of Congress on both the lack of a declaration and the lack of an appropriation.

Will court ignore precedent?

The greatest hypocrisy is the authority that the Democrats intend to use in this challenge.

In 2016, I represented the House of Representatives in challenging one of Mr Obama's unilateral actions, after he demanded funds to pay insurance companies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Every year, presidents must ask for appropriations of money to run the government - a critical check on executive authority held by the legislative branch.

Congress refused so Mr Obama simply ordered the Treasury would pay the companies as a permanent appropriation - even though Congress never approved an annual, let alone a permanent, appropriation.

Mr Obama did not declare an emergency, he just took the money. Nevertheless, Ms Pelosi and the Democratic leadership opposed the lawsuit and declared it a meritless attack on presidential authority. We won the lawsuit.

In addition to ruling that Mr Obama violated the Constitution, the federal district court in Washington, DC, ruled that a house of Congress does have standing to bring such a lawsuit - a precedent that Congress had sought to establish.

Now Democrats are going to use the precedent that they opposed under Mr Obama. However, they could end up not only losing the challenge but frittering away this historic precedent.

Where will the $8bn come from?

$1.4bn from the agreed budget

$600m from cash and assets seized from drug traffickers

$2.5bn from a defence department anti-drug trafficking fund

$3.5bn reallocated from military construction projects

Courts often turn to standing to avoid tough decisions. Since the Democrats are likely to try to litigate this question in the Ninth Circuit which covers California and some other western states, the judge will not be bound by the DC ruling and could rule against the right of Congress to bring such actions.

Moreover, the litigation to the Supreme Court could easily take two years. Once there, the challengers will face a newly minted conservative majority with two Trump appointees.

That would mean that the Democrats could hand Trump a major victory on his signature campaign issue just before voters go to the polls in 2020.

A different age

That brings us back to the night Franklin and Adams had to share a bed. The two founding fathers were going to meet Admiral Richard Howe of the British Royal Navy in Staten Island to discuss the possibility of ending the Revolutionary War.

They found themselves in New Brunswick, New Jersey, at the Indian Queen Tavern. However, it was full and only one room with one small bed was available.

Two of the most irascible framers of the US Constitution crawled into the small bed and immediately began to quarrel.

Franklin had opened up a window but Adams held the common view of the time that you could get ill from night vapours. Franklin insisted that cool fresh air was, in fact, a health benefit and added: "I believe you are not acquainted with my theory of colds."

Strange bedfellows... John Adams and Benjamin Franklin

They argued all night until Adams fell asleep. Adams simply wrote later: "I soon fell asleep, and left him and his philosophy together."

It is perhaps a lesson for our times.

While the debate over open windows as opposed to open borders differs by a certain magnitude, there was a time when entirely incompatible politicians could reach an agreement.

Sure, it was by exhaustion rather than persuasion, but the dialogue continued to a conclusion without enlisting a federal court.

If the Democrats lose this case shortly before the 2020 election, they may wish they had tried the one-who-can-stay-up-the-latest approach to conflict resolution.

Jonathan Turley is the Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University in Washington, DC.