Queerbaiting - exploitation or a sign of progress?

- Published

Grande has been a strong advocate for gay rights

Ariana Grande stands accused of manipulating her gay fans by suggesting in one of her songs that she may be bisexual. So what is so-called queerbaiting?

Grande's new song, a collaboration with friend Victoria Monét called Monopoly, claimed the number one spot on the iTunes chart 24 hours after its release.

But a particular lyric, in which Grande sings of liking "women and men" has added scrutiny to the customary buzz that now follows the American singer.

Some fans have celebrated it as an expression of bisexuality. Others, however, have levelled charges of queerbaiting, which is the practice of using hints of sexual ambiguity to tease an audience.

"Queerbaiting isn't new but it's implications are as powerful as ever", said Julia Himberg, professor of film and media studies at Arizona State University and author of the book The New Gay for Pay: The Sexual Politics of American Television Production.

Prof Himberg and other experts on queerbaiting say it was born out of fandom in the early 2010s.

Devotees of shows like Supernatural and The 100 - both from the CW television network - and BBC's Sherlock took to Tumblr and other social platforms to debate the apparent subtext of LGBT relationships between characters.

"They're falsely leading us on," says Eve Ng, professor of media and women and gender studies at Ohio University. "Viewers feel misled... making us think you're actually going to deliver a satisfying narrative but it doesn't turn out."

Some fans of Sherlock say the dialogue suggests a level of intimacy beyond a friendship

The accusation is that these plots are a calculated strategy.

"This is about also targeting multiple audience demographics where you're not offending a conservative audience and you're also signalling to an LGBTQ audience that you want them as well", says Professor Himberg.

In the case of Grande, who has earned a reputation as an advocate for gay rights, her veiled references to same-sex relationships - both in Monopoly and a recent music video where she signals a kiss with a female actor - are not paired with any explicit confirmation of their meaning.

"Our identities have been used over and over again in popular culture to establish an edgy identity", says Prof Himberg. It's offensive when someone seems to be playing with it, she adds.

"There's this sense of - don't tease us, don't use us," she adds. "It can easily feel like a cheap marketing tool."

The principal concern is that gay culture is being commodified, says the professor - used as a tactic to sell records and expand viewership among those seeking a wider representation of LGBT people in the media. But it's a tease to grab attention and has no substance.

But others see in the very existence of queerbaiting an improvement in the media representation of gay relationships.

"It's only because LGBTQ representation has improved that people would accuse producers of queerbaiting," says Prof Ng.

"It's progress. Ten to fifteen years ago, the majority of female fans would have been super psyched if an artist like Grande or someone of her stature said something like that."

It's why sexually ambiguous artists of the past managed to dodge some of this intense scrutiny.

The sexuality of David Bowie, Elton John and Madonna was not examined to the same degree, says Prof Himberg.

"LGBTQ audiences were hungry for representation and those stars provided it. We live in a different moment today."

David Bowie was one of the first artists to be sexually ambiguous

Queerbaiting is contextual, says Prof Ng, who believes the current frustration is born from a "mismatch" between what viewers expect in gay and lesbian representation and what pop culture is actually providing. Now that people are getting used to increased representation, they want more respectful and meaningful depictions.

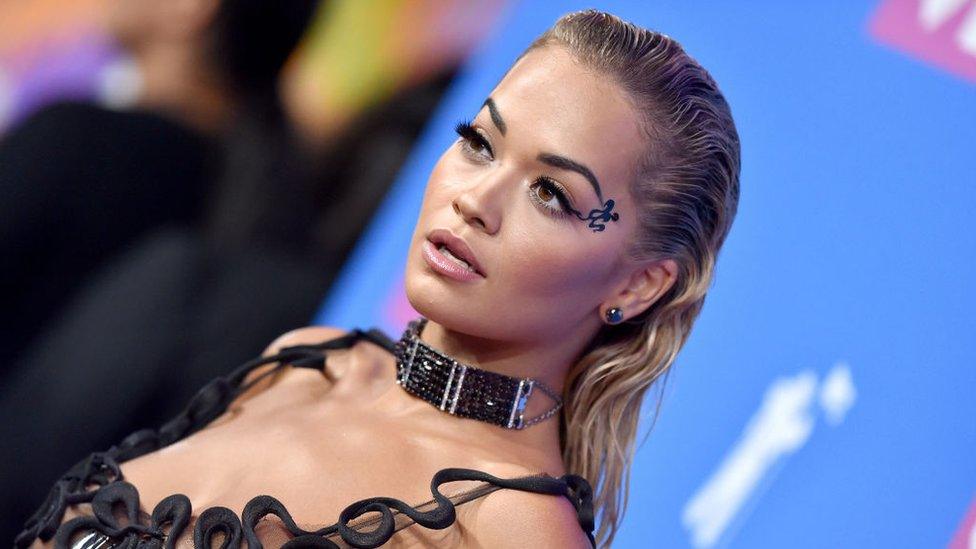

Grande is not the first singer to be accused of baiting gay audiences. British singer Rita Ora faced a backlash last year for her song Girls, which described sexual relationships between women.

Ora quickly responded to this criticism, posting an apology to Twitter in which she came out as bisexual.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Her statement, particularly the disclosure of her own sexuality, provided a powerful rebuttal to the notion of queerbaiting.

"We can't demand that anyone express their sexual orientation or gender identity in any particular way", says Sarah McBride, national spokeswoman for the Human Rights Committee. "I think that is an overriding fact."

Following the release of Monopoly, Grande herself addressed public calls demanding she label her sexual identity.

"I haven't before and still don't feel the need to now," she said.

But while advocates of equality agree that expressions of sexuality should not be policed, the modern aversion to labels can also pose problems.

Ora came out as bisexual after being wrongly accused of queerbaiting

"In some ways that can feel like an erasure of LGBTQ identities", says Professor Ng. "People fought for the right to call themselves lesbian and gay,"

And the modern proclivity toward fluidity can allow producers and performing artists to capitalise on the popularity of gay and lesbian identities, while sidestepping most of the discrimination and abuse levelled at these communities.

Perhaps most of all, the queerbaiting debate underscores the significance of media representation in defining and understanding LGBT identities.

"The baseline is that representation is critical," says Ms McBride. "For a young queer person… seeing themselves reflected on stage or in music or in movies, that can be not just life changing but also life saving."

And the discussion provoked by songs like Grande's may improve the quality of that representation, she says.

"Art that can inspire and empower and comfort. Art that can educate... that's powerful."

- Published29 July 2017

- Published13 July 2018

- Published22 July 2018

- Published9 August 2018