Birmingham, Alabama: A city using theatres to reinvent itself

- Published

The Lyric theatre's dramatic makeover has helped reinvigorate downtown Birmingham

"The idea of saving a theatre is so common that it is the plot of the Muppets," jokes Glenny Brock, a resident of Birmingham, Alabama, who left her job as journalist to work full-time on such a project.

She cites a past headline on the satirical news site The Onion: "Community loses interest three days after rallying to save local theater".

Yet in Birmingham's case, the locals have made it work. Its theatres are undergoing a renaissance.

First came The Lyric, which reopened in 2016 after decades of neglect, then the Alabama Theatre set to work restoring the second of its dazzling, 60ft signs.

Now work on the art-deco Carver Theatre, which served the African-American community, is also under way.

The Alabama Theatre's interior was renovated in 1998, the exterior signs are still being worked on; it was built in the 1920s for silent movies, hence the Wurlitzer organ on stage

Birmingham, named after the UK city on account of its industrial aspirations, remains best known for being the centre of the country's civil rights struggles in the 1950s and 1960s, and that is why the restoration of its past, through a modern lens, is seen as so important.

Next in line for a makeover is another abandoned African-American theatre, The Lincoln, in Bessemer, 15 miles (24km) to the city's south-west.

It has been bought by actor André Holland (Moonlight; Selma; Othello at Shakespeare's Globe), who grew up in the town and remembers it as an empty shell next to his childhood barbers' shop.

He says people are really excited about his plans to turn it back into a cinema and arts space, especially as it sits in a predominantly African-American area that feels like it is often left behind.

"It's good for people - particular young people - to have something to be proud of in their neighbourhood," he says. "The Lincoln was the only movie theatre you could go to [as a black patron in segregated Bessemer]. Everyone who went has memories of it. They remember first dates there, they remember the titles of all the movies they saw."

The actor picked up the keys a year and a half ago, and is currently still in the early stages of planning its resurrection.

"It looks like someone just locked the door and walked away. The movie reels are still there, there is an old projector," he says, clearly in awe of its history and potential.

The Lyric returns

The Lyric, in downtown Birmingham, has been the most jaw-dropping of the theatrical transformations to date.

For more than 45 years, it was largely abandoned - aside from brief spells of use, including as a retail space and a porn theatre.

To a passerby, it looked like a forgotten corner of standard office block. The birds, bats, rats and cats had moved in, according to Ms Brock, who works for non-profit organisation Birmingham Landmarks, which spearheaded its renovation.

An $11m (£8m) project has brought it back to its full glory, recalling days when its Buster Keaton, Mae West and the Marx Brothers all trod its boards.

The Lyric - which opened in 1914 - as it looked before it was renovated

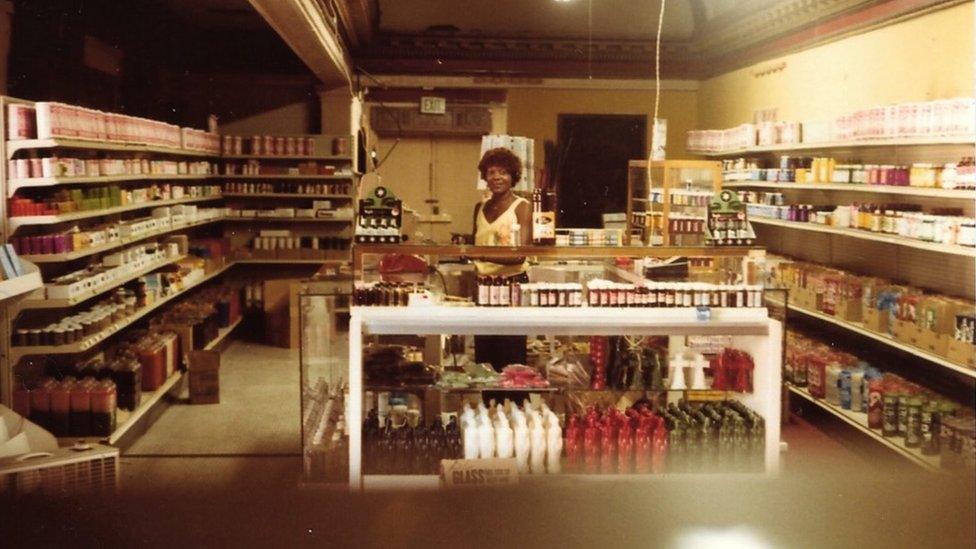

People used the Lyric's empty space as a makeshift shopping area during the down years

The Lincoln theatre, in Bessemer, is awaiting its turn to shine after being bought by a film star

The Lyric closed in 1960, four years before Birmingham's segregation law was overridden by the Civil Rights Act. Before then, black patrons had to enter through a separate entrance and sit in the "coloured balcony", way up in the gods.

When restoring the building, the lobby's separating wall was knocked through and a glass panel was put in to highlight this. An engraving reads: "Historic colored entrance. You are standing before a reminder of Birmingham's history and the struggle for civil rights".

One city, two theatre scenes

For most of the first half of the 20th Century, Birmingham had more than 20 theatres within five blocks, but they catered to different races.

The Alabama Theatre became open to African Americans after the city's segregation order was rescinded in 1963

With much of the city out of bounds to black customers, a cluster of streets - now known as Fourth Avenue Historic District - developed as a separate business district, with its own barbers, restaurants and theatres.

"It was an independent economy and ecosystem," says Elijah Davis, who works at Urban Impact Inc, the area's non-profit development agency. "And it was not razed to the ground in the 70s like many such areas in other places."

Urban Impact was founded 39 years ago by the city's first black mayor, Richard Arrington. Among other things, it helped the district's businesses buy their premises from absentee landlords.

Most of the area's theatres were never black-owned, says Mr Davis.

The Carver's comeback

In its heyday, Fourth Avenue Historic District's theatres had four theatres. Two are no longer there, one has been transformed into apartments and the fourth, the Carver Theatre, was bought by the city in 1990.

It is currently closed as its renovation begins and the project is expected to be completed next year.

The Carver Theatre pictured in 1949; it opened in 1935

The Carver has recently been home to the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame museum

The Carver was a thriving venue in its heyday, says Leah Tucker, its executive director. "It was somewhere to get dressed up and feel comfortable."

She says its restoration is important for the African-American community - to show its heritage is worth protecting too - and for all residents and visitors. "Most tourists visit for Birmingham for the civil rights experience. It [the preservation] can help the city."

In 2017, the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument District - including part of Fourth Avenue area - was protected via a proclamation signed by then President Barack Obama.

Birmingham reborn

All of the theatre restorations are helping the city move forward.

Ms Brock says the Lyric's restoration has led to businesses - from a hip coffee shop to a ramen bar - springing up around it, and new apartments are making the downtown area an appealing place to live.

The 2011 inauguration of Railroad Park, which transformed industrial space into parkland, was also another key marker in this apparent turnaround, while the ever-expanding University of Alabama at Birmingham is also bringing new investment and more downtown residents.

However, architecturally, the city still mourns the lose of its grand, Byzantine-inspired train station, which was demolished in 1969. "That is like a civic wound," says Ms Brock, adding that Lyric presented "an incredible opportunity to get things right".

Birmingham terminal station, circa 1940

Mr Davis agrees that the new Lyric is a "hallmark" of downtown revitalisation. "And we also have buildings that are really able to subvert ideas on what African Americans were able to accomplish in Jim Crow times in the south."

He said there was a lot of excitement brewing around the long-awaited new Carver.

"Birmingham is very much wrestling with the type of city it wants to be," he says, referring to issues of gentrification and displacement. "But contrary to other cities of its size, it is probably having the right conversations early on."

All photographs subject to copyright

- Published9 March 2015

- Published26 September 2018

- Published1 December 2018

- Published16 August 2018