Tintoretto: A 'colossal' painter arrives in America after 500 years

- Published

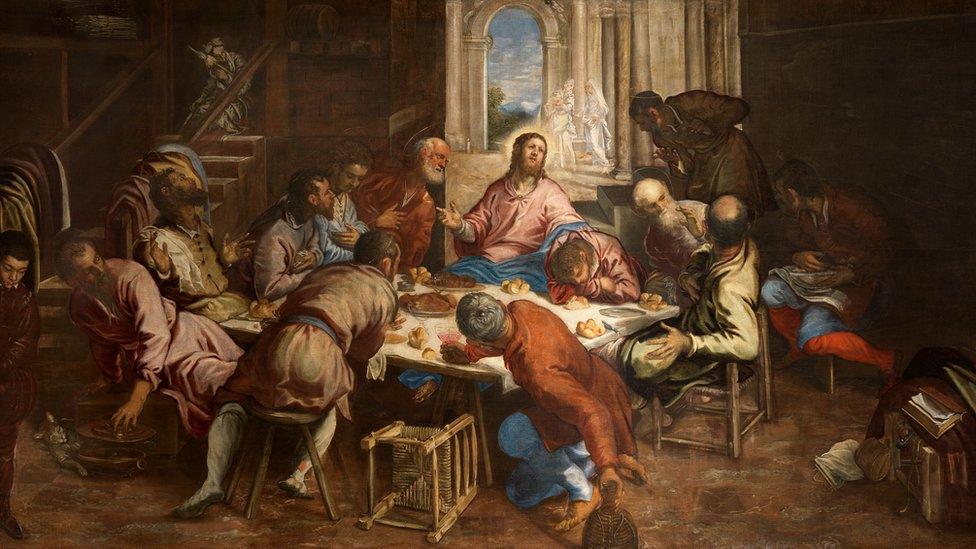

The Last Supper, circa 1563/1564

It's taken 500 years, but Tintoretto, one of the great masters of the Renaissance and a giant of European art, has finally made his debut in the US.

For the first time, some of his finest paintings have been brought under one roof at the National Gallery of Art in Washington for a massive exhibition to celebrate the approximate anniversary of the artist's birth - around 1518 or 1519.

Some of the works in the show have never before left Venice where Tintoretto lived and worked for 75 years. Others couldn't be included because they were too big to fit through the gallery doors or too fragile to travel.

"Tintoretto worked on an enormous scale," says exhibition co-curator Frederick Ilchman. "He had this ambition to cover every wall of his native town and he really thought big. For him, the way to convey urgency was to do things on a colossal scale."

Co-curators Robert Echols (L) and Frederick Ilchman

His real name was Jacopo Robusti - he adopted the nickname Tintoretto which means "the little dyer". He was a pioneer in the new format of the era - oil on canvas.

He was an innovator, constantly looking for new ways to bring to life stories from the Bible and classical mythology. Drama was more important to him than a smooth finish.

Oil paints on a rough surface gave artists the ability to experiment with size and texture. And instead of people travelling to see the art in situ, canvasses - even very large ones - could be rolled up and shipped across the world.

To drive the narrative of his paintings he used the human figure - usually muscular and often drawn from life. They lead the viewer's eye through complex scenes with dramatic gestures and poses, sometimes in surprising ways.

"He wants to make you look harder," says Mr Ilchman. "You take something more seriously if you can't figure it out immediately. There's a sense of asking us to participate in the process, just like he would have pondered the subject matter before he started to paint."

St George and the Dragon, painted around 1560, is one of his best-known works and shows the scope of his experimentation.

As St George slays the beast in the background, it is the princess, not the hero who grabs our attention. She rushes towards us, seeming to leap out of the canvass, her crimson cloak billowing behind her. The strange light adds to the tension.

Saint George and the Dragon

And while many artists have depicted the biblical story of the Last Supper with dignity and restraint, Tintoretto's disciples are clearly shocked and horrified to learn that one of them will betray Jesus by morning.

In his most famous version of The Last Supper (1563/1564), they recoil from the news, or lean in to listen more intently. A chair is knocked over while a grey tabby cat seems to take advantage of the confusion to sniff a bowl of food on the floor.

Tintoretto was also prolific, running a workshop to churn out his paintings to keep pace with commissions. In the 16th Century, Venice was a commercial and creative hub for artists who included his great rival Titian.

"Titian - 30 years older - really wanted to block Tintoretto whenever possible. But Tintoretto made specialties of very large format religious paintings, something that Titian, once passed middle age, really wasn't up for any more," says Mr Ilchman.

You may also like:

Renaissance masterpiece rediscovered

With so many of Tintoretto's big kahunas on display, it might be easy to overlook his portraits which are grouped together on one wall.

"His narrative paintings are dynamic, they're overflowing, they're expansive. His portraits are interior, pared down," says co-curator Robert Echols. "We'd never think really that this was the same artist."

Tintoretto's The Virgin and Child with Saints"

But nevertheless, Tintoretto's portraits rank among the best of the 16th Century and inspired later artists such as Rubens, Rembrandt and Velasquez.

"Tintoretto's sitters look you directly in the eye. It seems like they've just seen you. That gives them a very contemporary feeling. You feel that these are people you might know today. Walking down the streets of Venice, you might recognise one of these sitters," says Mr Echols.

Tintoretto was particularly skilled at painting old men which was just as well as there were a lot of them in Venice at the time.

One of the portraits here, Man with a Red Beard (c 1548), has only recently been identified as Tintoretto's work and is being exhibited for the first time.

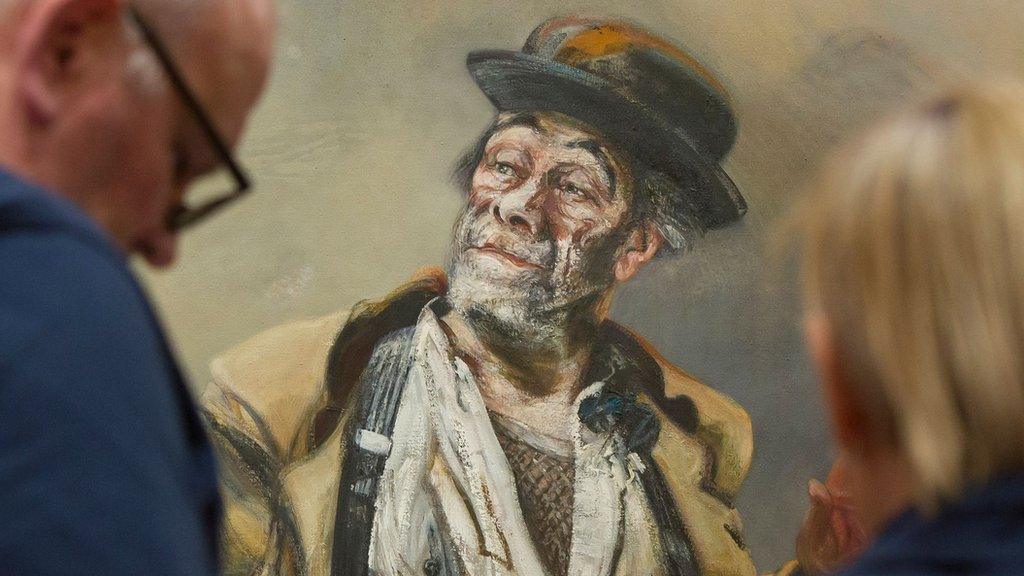

A woman examines the artist's Portrait of a Widow

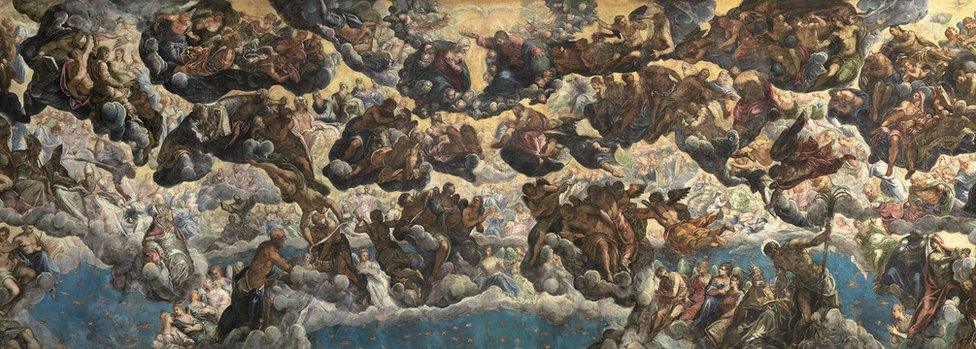

One of the most spectacular paintings at the National Gallery of Art is Tintoretto's vision of paradise (Paradiso, modello c 1583).

More than 16ft-long (five meters), it was the equivalent of an enormous business card as he used it to audition for a commission to paint the Doge's Palace - the principal government building in Venice.

Paradiso, modello, circa 1583

Paradiso is considered an oil "sketch" to be used for a larger palace painting

Unlike the finished wall piece, this monumental oil "sketch" is done entirely in his own hand and is a riot of figures and movement surrounding Christ crowning his mother Mary as Queen of Hearts. Modern critics like it much more than the final version.

As they researched and assembled the works for this exhibition, Mr Ilchman and Mr Echols discovered more about Tintoretto's way of working.

Many paintings were restored for the anniversary thanks to a $1m (£777,000) donation from Save Venice, an organisation dedicated to preserving the city's art and architecture.

X-rays and infrared reflectography have allowed conservators to peer beneath the top layers of paint to see how Tintoretto plotted his compositions.

He would often use a grid to transfer a small drawing onto a big canvas which counters the notion that he was careless and haphazard. His self-portrait (1546/1548) certainly gives that impression with his unruly hair and confrontational gaze.

The curators also learned a lot about the pigments he used.

"Many of paintings, particularly in his later period were pretty brown and dark, a kind of monochromatic palette, as if he's deliberately being more sombre in his later art as he heads towards death," says Mr Ilchman.

But Tintoretto, who died of a fever in 1594, may not have been as depressed by thoughts of his own mortality as critics initially thought.

Having the Sistine Chapel in your living room

"Instead it turns out that many of those landscapes would have been a rich green. It's just that the pigment, the mineral has changed over time with the contact with the oil. It is kind of misleading."

That suggests that two huge canvasses of the Virgin Mary reading and meditating (1582/1583) - which have never before shown outside Italy - may have been far more vibrant than they are today with bright blue skies and greener landscapes.

Visitors to Venice can still see the finest single collection of works by Tintoretto at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, headquarters of a charitable confraternity or guild to which Tintoretto belonged.

"But with the exception of that building," says Mr Ilchman. "I'd argue that this suite of galleries here in the National Gallery of Art really shows the best of this artist and why he still packs a punch centuries later."

- Published9 April 2019

- Published7 June 2013

- Published15 March 2019