Canadian national inquiry: Giving a voice to missing and murdered women

- Published

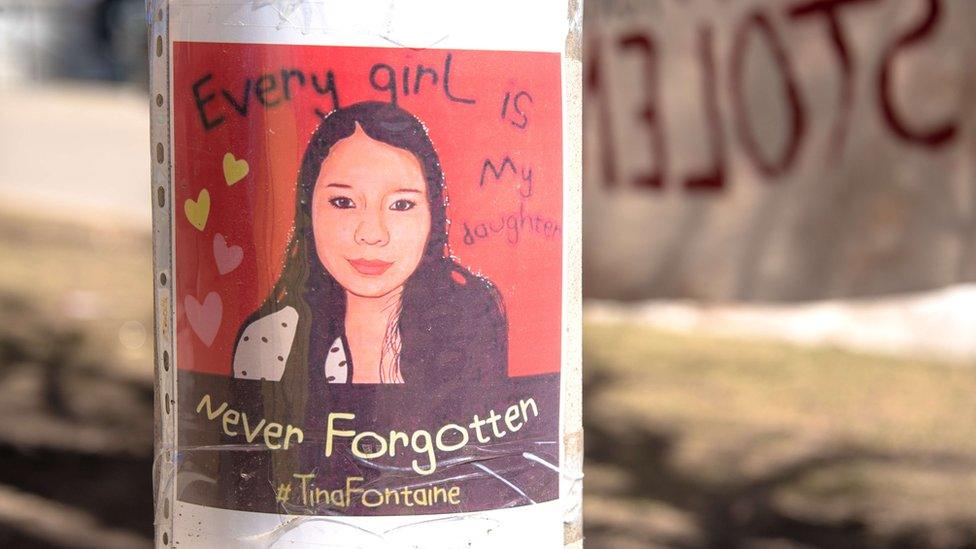

A poster commemorates Tina Fontaine, a young indigenous girl who was killed in 2014

After over two years of work, Canada's inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women has concluded and the report reached the public domain. We spoke to two of the women who fought for years to bring global attention to the violence.

It has been almost 50 years since Helen Betty Osborne - a Cree woman who dreamed of becoming a teacher - was abducted and brutally murdered near The Pas, Manitoba, a town deeply divided along racial lines, its white and indigenous residents once described as "world's apart", external.

In many ways, the death of the 19-year-old was indicative of cases to come - an indigenous teenager forced to leave her remote community, targeted by four men simply because of her race, and a family's long wait for justice.

Fifteen years ago, Amnesty International called the assault and murder of the shy young woman "an unheeded warning".

The violence faced by indigenous women and girls is now in the spotlight as a national inquiry into missing and murdered women drew to a close after more than two years of hearings and testimony.

"It took 40 years to get to this present moment and only because indigenous women have been on the ground making noise about this," said Robyn Bourgeois, an academic and activist who researches female indigenous activism in Canada. "Without them we wouldn't be here," she said.

The campaigners include family members victims who have campaigned tirelessly for their lost loved ones, and grassroots organisers and activists like Beverley Jacobs and Terri Brown, who also lost family members.

For Jacobs, the murder of her 21-year-old cousin Tashina General in 2008 was a turning point in her work. For Brown, whose 41-year-old sister, Ada Elaine, died in 2001, the loss continues to haunt the family, who say she was murdered and that her case was mishandled.

Jacobs, a Mohawk lawyer, was the lead researcher of the Amnesty report into discrimination and violence against indigenous women, and spent months travelling across the country meeting the families of women who had disappeared or been killed.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledges to tackle violence against indigenous women

"At the time it was the families doing all the work," she said. "They were the ones doing the poster boards, and the searches, having a really difficult time with police, just not getting any answers."

Her endeavour began just as a related, horrific murder case was about to make headlines around the world.

Police had arrested Robert Pickton, a serial killer who had been preying on women from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside district for years - many of his victims indigenous, many of them marginalised.

Authorities had long denied there was a pattern to the disappearances, or that they might be linked.

A subsequent provincial inquiry laid bare the systemic failure and bias that allowed Pickton to murder women for years without being caught.

Pickton was eventually sentenced to life in prison for the murder of six women. He had initially being charged with killing 26 women from a total of 69 who had gone missing throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

His high-profile trial brought with it a growing suspicion among campaigners like Jacobs that what had happened in British Columbia, where indigenous women were disproportionately reflected among women reported missing or killed, would be seen on a national level.

"That [case] was a leverage point," Bourgeois said.

Many of Pickton's victims were from Canada's marginalised indigenous community

It was also where Jacobs, the Mohawk lawyer, began her work. "The first task I thought I needed to do was to go to the Downtown Eastside because Pickton had just been arrested," she said.

Women who had been working for years to bring attention to what was happening brought her to the killer's pig farm, the site of the murders.

"It was horrible. It was before any trial, I'm not sure if any charges were laid yet. But [investigators] were digging up the ground," Jacobs said.

'Possibly disbelief, possible fear'

Brown, a long-time indigenous activist and, like Jacobs, a former president of the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC), was instrumental in raising the alarm about the "horrific number of women" who were disappearing in Vancouver.

Under Brown's leadership, NWAC collaborated groups like with Amnesty, Kairos - a faith-based group - and the Anglican and United churches to create a national awareness campaign.

But Brown says it was a repeat of Vancouver - they were most often met with indifference. There were also significant gaps in record-keeping, making it difficult to gain a full picture of the violence.

Some unofficial accounting of the missing was taking place. In Toronto, Amber O'Hara - an Anishinaabe woman and Aids campaigner - began compiling an online database. And according to Brown, women in the Downtown Eastside "were doing great work, they were keeping count of the women who were being lost".

"Families would come in and say 'We haven't seen her for weeks.' And police would say 'Maybe she's on vacation somewhere'. Well excuse me, they never left that 100 block of the Eastside."

Brown, then heading the Native Women's Association of Canada, decided there needed to be a formal compiling of the data.

"I wanted to put numbers to this because no one believed us," she recalled. "But we didn't have the resources, I did my own research and presented it but they said: 'Well, how do you know that it's true?' At that point we said there were about 500 missing and murdered aboriginal women."

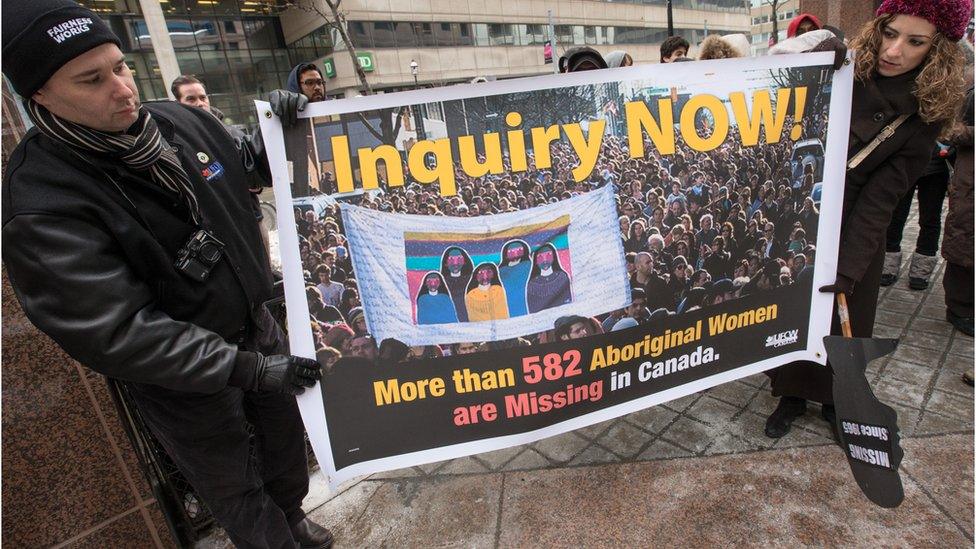

People at a rally in Toronto in 2014 demanding a national inquiry

The association secured federal funds to found the Sisters in Spirit campaign, which researched and raised awareness of the high rates of violence against indigenous women. By 2009, they had compiled 520 names, external.

Still, Brown remembered bringing the statistics to meetings with government officials - even some indigenous leadership, she said - and it was "the strangest thing" to present the data, "to people who would just sit there and look at you, not respond, not say anything, not be encouraging, not be giving of their support in anyway".

"Blank. Possibly disbelief, possible fear. I don't know."

The statistics

To this day, a lack of hard data means no one knows exactly how many indigenous women and girls have been murdered or have gone missing in the past decades. But some statistics have been compiled.

10% of all women reported missing are indigenous and they account for 21% of female homicide victims. Indigenous Canadians represent about 4% of the population.

Half of the homicides were committed by a family member, but indigenous women are also 1.4 times more likely to be killed by someone they aren't close to.

In 2014, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police identified almost 1,200 cases between 1980 and 2012.

Indigenous women are at a greater risk of physical and sexual assault - even when other risk factors are taken into account - and experience more violence from their intimate partners.

Bourgeois and Jacobs tried a different tack. They went to the international stage. Brown began to raise the issue at UN meetings and elsewhere.

"Everywhere I went I would mention it," she said. "Not that anyone cared. But I thought at some point someone is going to listen."

Jacobs said they knew Canada wasn't doing anything. "And we knew that the international forums would bring the attention against Canada," she said. "[On the international level] there are no enforcement mechanisms. The only way is to bring embarrassment to the country."

Tina Fontaine died in August 2014, aged just 15

Then in August 2014, 43 years after Osborne's murder, another case - this time the death of a 15-year-old schoolgirl called Tina Fontaine - began to make headlines across Canada.

Her murder sparked a collective and fierce outrage and consolidated calls for a national inquiry.

By 2015, the UN was pushing for a public inquiry, as did a landmark Canadian report, external into reconciliation with indigenous peoples.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau officially launched one a year after winning the 2015 general election.

By then, Brown and Jacobs had stepped away from national advocacy on the issue. Both say it took its toll emotionally, especially given that both had themselves lost loved ones.

Jacobs: Canada needs to 'accept responsibilities'

"I felt I couldn't do it anymore. I got too angry," said Jacobs. "From the time I started to [after my cousin's death] I just felt I was banging my head against the wall, I felt like nothing was getting achieved."

They have also been critical of the inquiry itself. Jacobs said it never managed to truly gain the trust of many families who lost sisters or mothers or daughters, and many were not included in the public hearings.

According to Brown, "They talked to a lot of families, opened a lot of wounds. But in the end did anybody get arrested?

"There has to be justice. Those men have to go to jail. If they don't, all the money spent and all what we talk about is not worth it, because there's no justice."

They also warned that, while the inquiry may have finished, rates of violence remained high.

True healing would come from indigenous Canadians reclaiming their culture, language, and traditions, Jacobs said.

She said Canada must take concrete steps towards reconciliation and taking responsibility for policies - from residential schooling, to the child welfare system and longstanding issues around land and treaties and more - that have been harmful to indigenous women.

These days, Brown shows up for vigils organised for the missing women and goes recognised, she said.

"Some young woman, inevitably at some point, will come up and start educating me on the issue and I just think, 'Yes, there's hope for us now.'

"Because they know the issue, They can name the issue, they have the strength to speak about it."

The final report

The path to the release of the national inquiry's final report hasn't always been smooth.

The C$92m ($68m; £53m) inquiry was launched in 2016 with a mandate to take an in-depth look into the underlying social, economic, cultural, institutional, and historical causes of violence against indigenous women and girls.

It held 24 hearings and "statement gathering" events across Canada, taking testimony from almost 1,500 people, including family members of missing or murdered women and survivors of violence. It also heard from dozens of experts and reviewed police and institutional files.

There have been resignations, delays, criticism related to transparency and communications, and concerns over its scope. Commissioners fought for a two-year extension but received just an extra six months from the federal government.

- Published1 November 2017

- Published12 March 2019

- Published26 April 2019

- Published31 May 2017

- Published25 March 2019

- Published13 February 2013