The mountain climbers showing diabetes doesn't have to be an uphill struggle

- Published

Climbing Denali has been the biggest challenge so far

Michael Shelver and Patrick Mertes both have a love of the outdoors and climbing. Neither has a functioning pancreas. How is type one diabetes affecting their bid to climb to the highest point in each of the 50 US states in just 50 days?

Being halfway up a mountain when you have a hypo - a low-blood sugar episode that can cause dizziness, disorientation and even unconsciousness - is far from ideal.

But it's a risk that friends Michael and Patrick are having to face every day as they aim to be the first with diabetes, they believe, to achieve 50 in 50. It's thought only 274 people have hit all 50 high points, most doing so over the course of their whole life, with just a handful going for the 50-day deadline.

Their mission, external is seeing them cover more than 16,000 miles, including hiking 315 miles of trails.

Their type one diabetes means their pancreas doesn't produce insulin, the vital hormone needed to allow cells to use glucose from food. Without insulin, your cells can be starved of energy and over time, dangerously high levels of glucose build up in the body.

If you have type one, insulin has to be injected, either manually or through an insulin pump, which Patrick and Michael use.

Patrick, left, and Michael at Mt Magazine, Arkansas

Too much or too little insulin can cause problems. And what makes the balancing act more difficult is that so many other things that can affect blood glucose - like exercise, altitude and adrenalin.

They started with the trickiest summit of all - the 20,310ft (6,190 metres) Denali in Alaska, North America's highest point. It was both a literal high for them, but also the source of dozens of low blood sugars as well as several episodes with ketones, a complication which can occur when blood sugars go too high.

'Hardest thing in my life'

Patrick, who has been living with diabetes since 1997, when he was nine, says: "What I've struggled with most so far was the altitude on Denali.

"We did it fairly quickly in terms of the standard route - most people take up to 17 days and we summited in nine. That did have some effect on blood sugar, as well as my pulmonary health.

"I'm not a very emotional guy, but reaching the summit of Denali was the hardest thing I've ever done in my life. Being able to not only attain that goal, but to do it with Michael, was next level for me."

Another in the long list of potential issues is that insulin does not like extreme environments.

They reached the summit of Kentucky's Black Mountain in darkness

Michael, who was diagnosed in 2004 when he was 10-year-old, explains: "We have to make sure our insulin is always in the normal temperature range, as it doesn't work properly outside of that.

"On Denali, we had to take our insulin and place it inside something padded - so in this case, we chose a sock - and then put that sock inside an insulated flask, and then sleep with that inside our sleeping bags. It can get up to -40F there - it was around -25F at the summit for us.

"We had to wear a lot of layers, with our pumps inside our inner jackets to make sure it stayed warm and that the tubing was OK, as that's more likely to freeze. None of it could be exposed to the air or it would freeze pretty quickly."

In Vermont, they were stopped by Devon Kirk, left, who happened to be climbing as part of a bachelor party - he was diagnosed three years ago. Here they all show off their continuous glucose monitors

Frozen insulin would mean it would not work, which could then lead to dangerously high blood sugar levels.

"In remote areas, we have to be sure we have adequate supplies and back-ups," he adds. "We can never be too far away from a pharmacy in case anything needs to be replaced - we can't afford not to."

Patrick says that at certain altitudes, they're "not using products the way they're meant to be used", adding: "So it's trial and error at that point."

What is diabetes?

Millions of people around the world have diabetes. The majority of them, about 95%, have type two diabetes, which means their bodies do not properly use insulin, a naturally-occurring hormone secreted by the pancreas. Insulin is needed to get glucose - formed when carbohydrates are broken down by the body - from the bloodstream into cells.

Type two diabetes can be controlled through diet, exercise, oral medication or a combination of all three. Sometimes it requires the use of insulin. Certain groups are more at risk of getting type two, and in the US it is more common in African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, as well as older people.

Type one is an autoimmune condition where the body does not produce insulin at all, so it has to be injected through the skin. It cannot be prevented at all and can occur in people of every race as well as every shape and size. It used to sometimes be known as juvenile diabetes, but this was not accurate as it is not a childhood disease and can be diagnosed at any age.

About 1.25 million Americans have type one diabetes, with an estimated 40,000 diagnosed each year.

Source: American Diabetes Association

The men have been friends since 2015, when they met while working for a type one diabetes non-profit organisation helping families affected by the condition.

They decided last year to plan a challenge that would allow them to bring people with type one diabetes together and to raise money for non-profit organisations helping get people with type one diabetes into the outdoors.

Others with type one have supported them on their journey

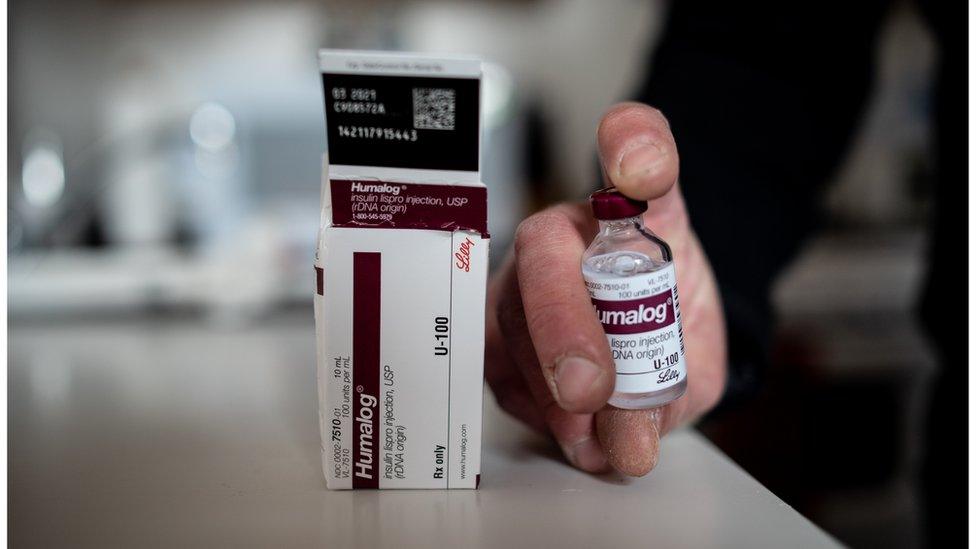

Snap - the insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors used by people with type one diabetes

Patrick says: "We have an affinity for adventure. I'd hiked the John Muir trail last year, and gave Michael a call afterwards, saying: 'I want to find a way to put together a big adventure with as many people from the type one community as we can'.

"It's nice having someone else with you who knows all about being out of [blood glucose] range. There's no one I would trust more doing this adventure with."

They spent the most time researching the technology they would use, choosing a continuous glucose monitoring system, which provides constant readings and information to your phone or a small device, instead of the old-school finger-pricking method of getting a blood glucose reading.

Their insulin pumps also use technology that can shut down insulin supply if blood glucose levels are heading too low.

They were projecting to finish in 41 days, but when they speak to the BBC - on their way to Spruce Knob, West Virginia - they're a day ahead of schedule and now expect to complete the challenge in 39 or 40 days.

There was time for an arm wrestling challenge at South Carolina's Sassafras Mountain

"There's been a real ebb and flow of energy levels," says Patrick. "We hit a wall today after getting in around 2.30am last night, then doing a nine-mile hike at 8.30am. But as long as we can get coffee in us and take the opportunity for rests when we can then we'll be OK. We feed off the energy from people who come out and meet us for the summits - it really invigorates us.

"Diabetes can be a really isolating condition - we don't necessarily look like we're sick or there's anything wrong with us. I think people have a hard time understanding it's a 24-7 thing. We never get a day off.

"So being able to build a community around type one can really transform how you see it. We wanted to prove to the rest of the world that if you plan ahead and have the right attitude, you can do anything with this condition."

You'd think that such a gruelling schedule would mean having a healthy appetite.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But Michael says: "Altitude can really affect appetite. My challenge at the moment is making sure that I'm eating enough. There's no consistency - we're never getting eight hours' sleep, and three set meals a day. We're sleeping a few hours at a time, living out of a van and then maybe eating at a gas station."

Patrick agrees, adding: "We're trying our best to get better at eating - but we're currently doing very well at living off granola bars and cheese strings. We've been so busy and have gone 12 hours and then realised we haven't had anything proper to eat, or we've just had snacks."

Michael says: "This whole experience is a metaphor for diabetes really. We've spent months planning for it - and then a huge storm can come in and change the plan. It's exactly how diabetes works. No matter how much you prepare, something is going to pop up."

Friends Annette and Sean joined the pair in Hawaii

Patrick sums up their mission this way.

"Multiple days, I've woken up and thought "what the hell am I doing?'.

"Then we'll have experiences that remind me of why we're doing this. In North Carolina, we did a hike with a high school freshman who's been experiencing some challenges. When we finished the hike, he said that it had helped him see there was a light in a dark tunnel - and now he says he's planning to hike the Appalachian Trail.

"If what we're doing helps just one kid, it's worth it."

Patrick and Michael have now completed the East Coast summits and are travelling to the Midwest before some of the bigger peaks on the West Coast. You can follow their progress here, external.

- Published14 March 2019

- Published10 July 2019

- Published27 March 2019

- Published14 November 2018

- Published19 October 2018

- Published11 July 2018

- Published22 October 2017

- Published1 December 2017