Richard Oland: A millionaire, a murder and a mystery killer

- Published

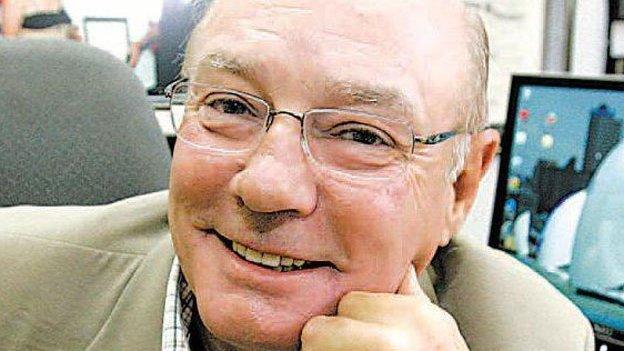

Richard Oland's wealth was about C$37m ($28m, £22m) when he was killed

Dennis Oland has been cleared of bludgeoning his millionaire father to death. For nearly a decade, the case turned one of the wealthiest families in the Canadian province of New Brunswick into the cast of a real-life soap opera.

Richard Oland was found face-down in a pool of his own blood on the morning of 7 July, 2011. He was 69 years old.

Forensic evidence suggests he was killed the evening before by 45 sharp and blunt blows to the head, neck and limbs. He was still wearing his Rolex watch, but his mobile phone, as well as the murder weapon, disappeared.

Two years later, his son Dennis Oland, now 51, was charged with second-degree murder. In 2015, he was convicted by 12 jurors of killing his father.

But that was just the beginning. Along the way, he won an appeal, appeared before the Supreme Court of Canada, and had a mistrial. His case captivated the community of Saint John, New Brunswick, who followed the twists and turns of the case closely.

"It's a bad soap opera - Days of Our Lives makes more sense," says taxi-driver Paul Savoie, who knows the rumours of Saint John almost as well as he knows its roads.

It was Richard's mistress who was the first to notice that something was amiss. For the past eight years, married realtor Diana Sedlacek had been having an affair with the tycoon. The relationship was, by most accounts, an open secret and when he didn't pick-up the phone for their nightly chat, she called his wife Connie to ask her where he was.

Dennis Oland leaves court on 19 July, with family

Connie became a key figure in the case, as she steadfastly stood by her son, contrasting his "gentle" and "caring" ways with her deceased husband's propensity for picking fights with his family.

"Dick Oland was an extremely prominent Saint Johner, that does not say that he was a well-liked Saint Johner from everything that I've heard," says Saint John criminal lawyer David Lutz. "People are concerned about whether or not poor Dennis is going to be convicted, as opposed to poor Dick."

The Olands weren't just rich - they were one of a handful of dynasties who had for the past century controlled the economy in the province like the Rockefellers and the Vanderbilts had once controlled New York City.

At the top of that hierarchy is the Irvings, who own a vast network of petrol stations, oil refineries, shipping docks and paper mills in the province and beyond. Next would be the McCains, who run the ubiquitous frozen food company.

Third or fourth on the list of New Brunswick dynasties would be the Olands, whose matriarch Susannah Oland founded Moosehead Brewery in Saint John 1867. Today it is the largest Canadian-owned brewery, and the Olands have repeatedly turned down offers to sell it to international companies.

That commitment to staying local has earned the Olands a lot of goodwill in the city of Saint John, which has shrunk from a population of about 90,000 in the 1970s to under 70,000 in accordance with the decline of major industries such as shipping and ship-building.

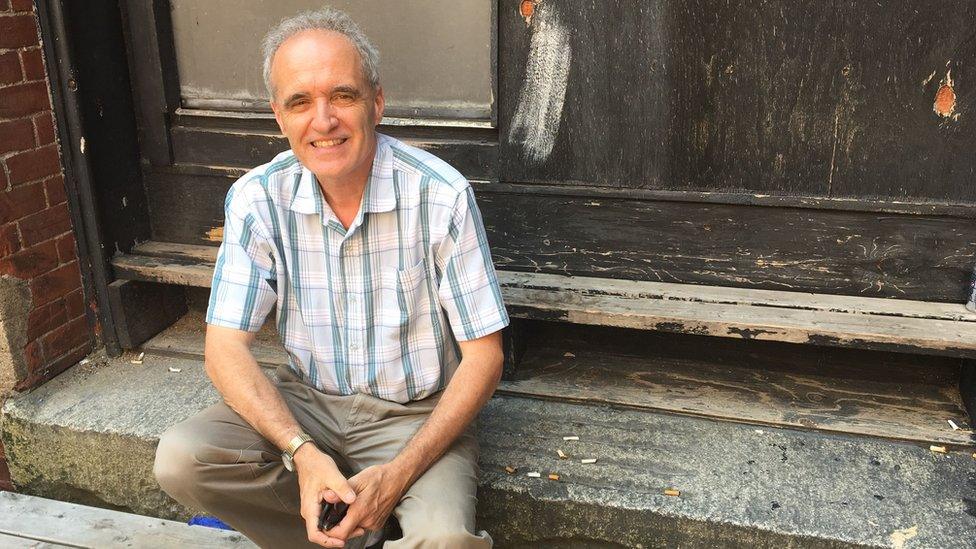

Greg Marquis grew up in Saint John and ended up writing two books on the murder of Richard Oland.

But the family's local profile has also made them an easy target for gossip, especially as the trial revealed details about the family's inner workings, its feuds and its finances.

"People felt 'oh here's that poor little rich guy'," says local history professor Greg Marquis. Growing up in Saint John, Marquis was an altar boy at the same church as the wealthy Olands, although he did not move in the same elite circles. He has since gone on to write two books about the case, and says Dennis's many trials have polarised the city along class lines.

When he was convicted during the first trial in 2015, Marquis says many of Dennis's defenders felt he was the victim of a kind of reverse-class bias. "Some people felt it was a blue-collar jury having their vengeance on an elite defendant," he says.

At the time of his death, Richard was worth an estimated C$37m ($28m, £22m) - and he didn't hide it. He raced yachts, was heavily involved in high-profile local philanthropic projects, and lived on a secluded estate not far from his son Dennis. But while the two were physically close, and indeed Dennis was named one of the executors to his will, they often clashed.

"He just barks and barks and barks," he said during an interview with police shortly after his father died. One Christmas in particular, he remembers his father screaming at him because he let the flame on a rum cake blow out before the dessert reached the table. "He could do things that could be hurtful."

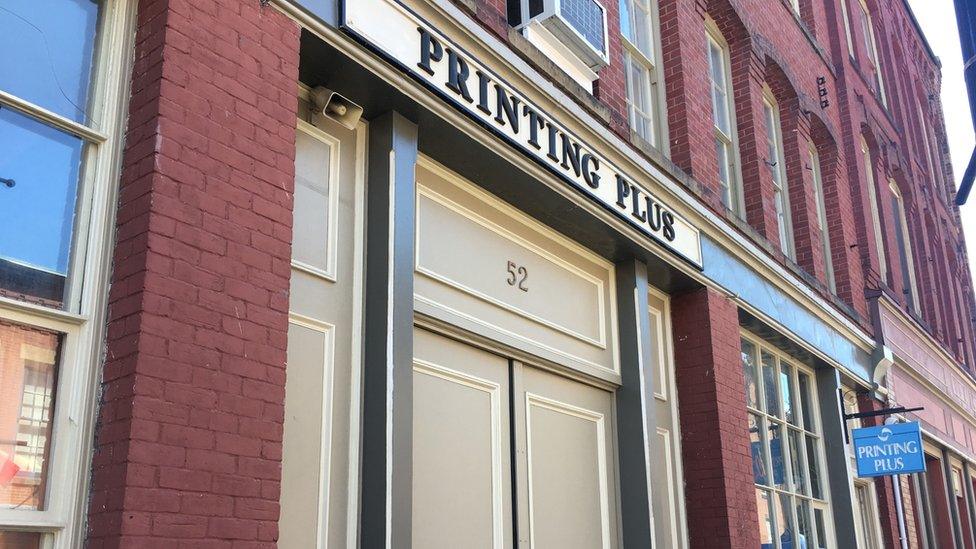

Richard Oland was found bludgeoned to death in his office, located above the Printing Plus

Strife between father and sons seemed to run in the Oland family. Richard's father Philip Oland, had been a strict disciplinarian who valued the family's legacy over its inner harmony.

When he chose Richard's older brother Derek to take over as president of the brewery in 1981, it left an irreparable rift between the two brothers. Richard spent most of the 1990s battling his brother in court for control of the company, and the two were on cool terms at the time of his death.

Despite his personal wealth, Richard could be stingy with those close to him - prosecutors say Connie was kept on a $2,000-a-month allowance, and expected to provide her husband with receipts of her purchases.

Meanwhile, he was having a new yacht built in Spain just a couple of years after he had purchased his "old" one.

He was willing to shell out cash to keep things in the family however. When Dennis nearly lost his house in his divorce, his father gave him a $538,000 loan. That loan became a key piece of evidence for the prosecution, who said in court that Dennis murdered his father over money.

The truth was Dennis, a financial adviser, was deep in debt. He had maxed out a $163,000 line of credit and a $27,000-limit credit card. The day before his father was killed, Dennis's monthly cheque to cover the interest on the loan bounced. But Dennis told the court money troubles didn't worry him. "It's stuff we always did and it was a continuation of that."

Lutz, a former vice chair of the Canadian Council of Criminal Defence Lawyers, estimates Dennis's legal defence is the most expensive murder defence in Canadian history.

Just days before Justice Terrence Morrison was due to deliver his sentence, the accused was calmly mowing the front lawn of his Rothesay estate. Wearing a T-shirt and shorts and riding a lawnmower, an observer might be forgiven for thinking Dennis was more concerned about the height of his grass than the impending decision.

Courthouse in Saint John, New Brunswick

On Friday, that decision was given. In a courtroom packed with friends and family, media and local onlookers, Justice Terrence Morrison pronounced Dennis Oland not guilty of murdering his father.

Though his decision exonerated Dennis, it did so with an asterisk. "There is much to implicate Dennis Oland in this crime," Justice Morrison said. "But more than suspicion is needed in order to convict someone of murder - probability is not enough."

The prosecution didn't have a murder weapon, a clear time of death or significant DNA evidence to tie Dennis to the crime. A few bloodstains matching Richard's DNA were found on Dennis's brown Hugo Boss sportcoat, but no blood was found in his car or on his shoes

His legal team says no other suspects were found because police had tunnel vision when they investigated him. He was the last person known to see his father alive. If the judge's not-guilty verdict was not a resounding endorsement of innocence, it will have to do. "In this case there are too many missing puzzle pieces," Justice Morrison says.

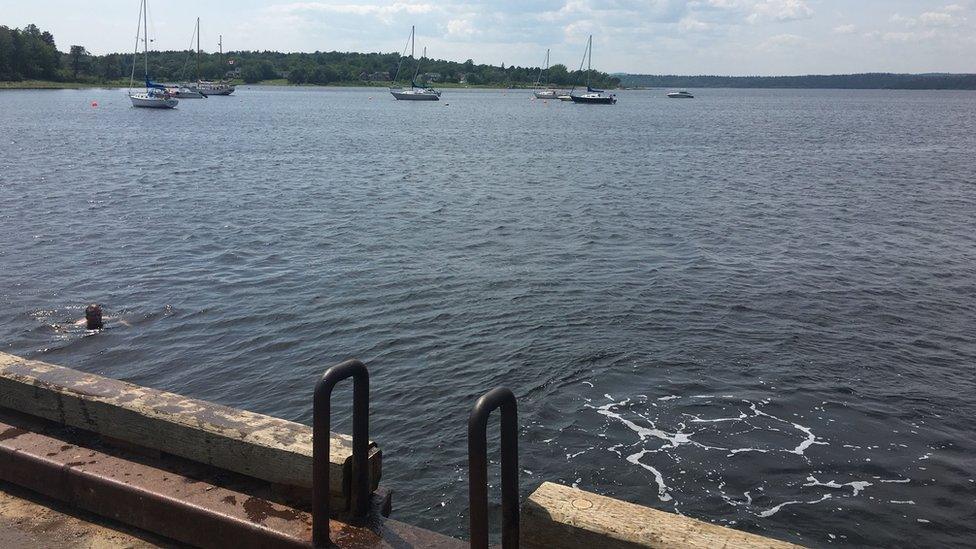

The view from the dock where Dennis Oland stopped the night Richard Oland was killed.

We know that on the night Richard died, Dennis stopped by his father's uptown Saint John office to talk about family history. Then Dennis got in his Volkswagen Golf and drove off towards his mansion located in the toney neighbourhood of Rothesay.

On the way, he made a stop at a nearby wharf. Sitting on the edge of the dock, he must have looked as if he was in a moment of philosophical introspection.

But what he thought about is still anyone's guess.