'Why I translate all of Trump's tweets into Chinese'

- Published

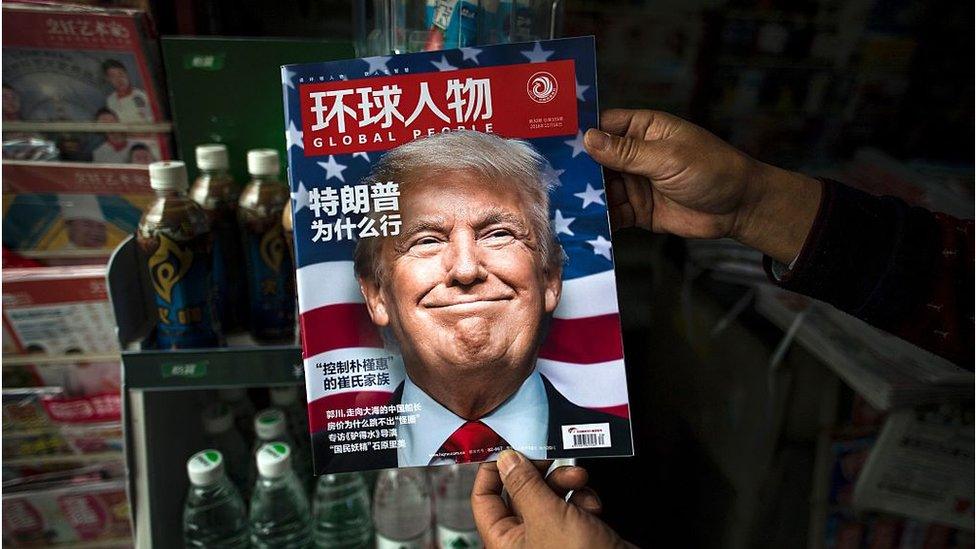

US President Donald Trump's trade war has enraged the Chinese government but it has also attracted some support among the Chinese people. A Twitter account run by Chinese immigrants in the US translates all his tweets for more than 100,000 followers - many of whom see Trump as a human rights advocate.

For at least four hours each day, Jeff Ding, 45, pays close attention to the Twitter account of @realDonaldTrump

With every new tweet, Ding rapidly translates the president's words into Chinese for @Trump_Chinese. The freelance engineering consultant in Los Angeles who hails from the same Central China province as Chairman Mao Zedong, is one of the three volunteers running @Trump_Chinese.

They are all Trump supporters that are critical of the Chinese government and hope to "spread Trump's messages in the Chinese-speaking world", says Ding. The account, which translates as "Trump's Chinese synchronous tweets" in English, notes its mission is to help followers "understand the theories of governance through Trump's tweets".

It launched in September 2018 and has more than 100,000 followers, although the only account it follows is, of course, @realDonaldTrump.

"We aim to service Chinese people around the globe, especially mainland Chinese who use VPNs to climb over the Great Firewall," says Ding. He translates the tweets into Simplified Chinese, which is used on the mainland. Traditional Chinese is used in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

China blocks selected foreign websites, including Twitter, and the invisible boundary between the domestic and global internet is commonly known as the Great Firewall. Some mainlanders use VPNs - virtual private networks which mask your computers location - to access Twitter, but it can be hard to estimate how many users exist.

Ding says his main motivation to maintain @Trump_Chinese is a strong belief that Trump is the most supportive president in American history for China's human rights.

He believes Trump's trade war applies pressure on China's economy, which will drag China into an economic recession. That downturn will challenge the Communist Chinese Party's (CCP) legitimacy and lead to its downfall.

When Ding encounters tweets that are tricky to translate, he consults Tang Baiqiao, a 51-year-old California-based Chinese political dissident who first came up with the idea of setting up @Trump_Chinese. Tang was a student activist during the 1989 Tiananmen Uprising and came to the US as a political asylum seeker in 1992.

In recent years, he has become one of the most fervent Trump supporters in the overseas Chinese dissident community. Additionally, Tang has a friend in the White House - he wrote the foreword to Death by China, a book written by trade adviser Peter Navarro, who is considered the main architect of Trump's China trade policy.

Trump's trade war on China brings "obvious" benefits to China's human rights, says Tang. The far-reaching economic sanctions aim to remove China's service trade barriers, like the country's bans on Gmail, Twitter and Facebook. In Tang's opinion, this also means no more internet censorship and publishing restrictions.

Tang has a personal relationship with Trump's China trade advisor Peter Navarro (far right)

Since the beginning of his campaign, Trump has used "China" as a trigger to rally supporters.

"We can't continue to allow China to rape our country, and that's what they're doing," Trump repeatedly said on the campaign trail, his words often met with raucous cheers of agreement. And as president, his trade war has shown little sign of stopping.

Trump's hawkish China trade policy has contributed to tensions between Washington and Beijing, while simultaneously attracting the support of people angry with the Chinese government.

@Trump_Chinese has become an outlet for the dissidents and dissatisfied. Every time Trump criticises China on Twitter, the account gets a particularly large number of comments and gains thousands of followers.

In May, Trump unleashed a series of tweets, announcing a plan to impose 25% tariffs on $325bn (£267bn) worth of Chinese goods. Chinese-speaking Twitter users passionately applauded his decision by commenting under @Trump_Chinese's related posts. "Excellent job! Please be more forceful!" "Wise and correct decision!"

One described his move as "a God-given opportunity" for overthrowing the Chinese government. Another wished Trump good health and re-election.

More on US-China relations

Chinese Americans 'Make America Dinner Again'

A month later, the trade talks took a turn for the better. Trump tweeted that he had "a very good talk" with President Xi Jinping and would not increase the tariffs. @Trump_Chinese was immediately filled with disappointment and outrage.

"I thought you were one of the greatest American presidents... It turns out that you may be just a businessman without moral principles," one commented. Some called him a "hypocrite".

Even though Trump is often fuming about China on trade, he has repeatedly praised Xi as "the most powerful [Chinese] leader in a hundred years" and his "good friend". Tang is not at all put off by these compliments, which he sees as Trump's diplomatic rhetoric and negotiation skills. "Slap you in the face, and then gently stroke it," he says.

The BBC visits the camps where China’s Muslims have their "thoughts transformed"

However, not all Chinese dissidents see Trump as a fighter for human rights.

"Trump started the trade war not aiming to promote freedom and democracy in China," says Teng Biao, a New York-based exiled human rights lawyer. "Objectively speaking, Trump's hawkish trade policy has given Beijing a hard time. However, fundamentally, he has no interests in improving China's human rights."

Before he fled to the US in 2014, the 46-year-old was once a lawyer and law professor in China. Teng is concerned that placing hope on the "morally-defected" president is a mistake, and that viewing the enemy's enemy as a friend will soon be proven to be "naïve."

Although senior officials in his administration have condemned China's human rights conditions, Trump himself rarely speaks specifically on the issues.

The group Chinese Americans For Trump holds a rally outside Trump Tower in June 2019

He has offered no words about the Muslim camps in the Chinese region of Xinjiang and has not taken a stand regarding the Hong Kong anti-extradition bill protests.

On 22 July, Trump said he was "not involved in it very much," and said the Chinese president had acted "very responsibly". On 1 August, he said it's up for China to deal with the Hong Kong "riots".

Fluent in both English and Chinese, Teng enjoys a large following on Twitter, but he thinks among outspoken Chinese dissidents, he and those who are anti-Trump are in a minority. But there's one thing that almost all of them agree on - when interpreting Trump's views on China, lines should be drawn between China the country, its people and the Communist government.

On @Trump_Chinese, "China" is often translated as "the Chinese Communist Party", especially in tweets where Trump is aggressively targeting Beijing. This reflects the dissidents' political thinking. "We're sons and daughters of China, not of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin," says Ding, calling it his guiding principle.

A ship carrying goods made in China arrives in Miami, Florida

Ironically, when translated into Chinese, Trump's tweets have striking similarities with the CCP's propaganda rhetoric.

"Change 'socialism or communism' to 'western capitalism', swap 'America' with 'China', then it's basically what you hear from Chinese propaganda," one commented on @Trump_Chinese, referring to Trump's tweets criticising communism and promoting American patriotism.

Trump often uses "great" to describe the country and people involved with the administration. So does the CCP.

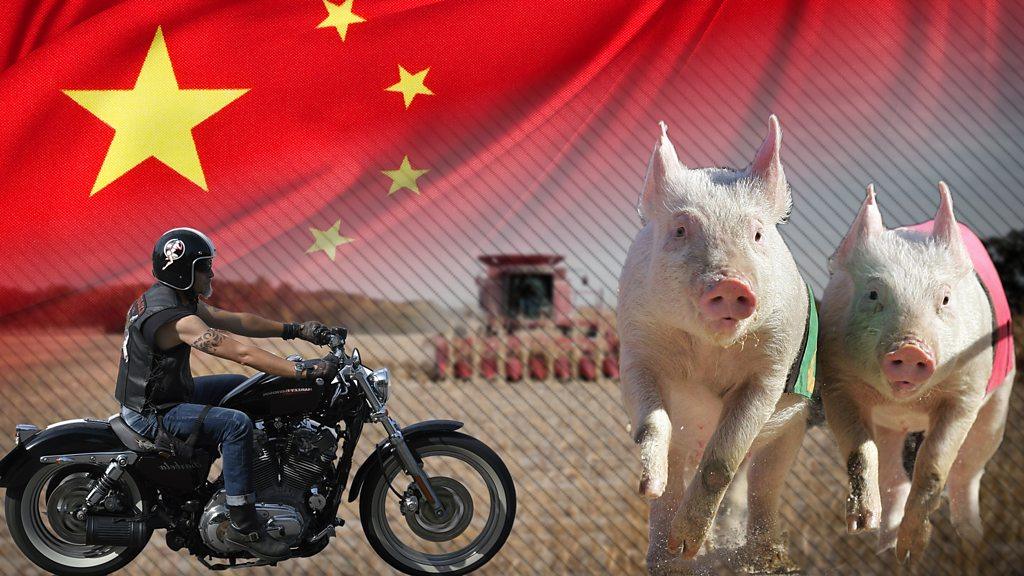

How hogs and Harleys became weapons in a looming trade war.

The Trump administration's distrust in China has left some worried that a new wave of "Red Scare" is approaching. Ding says he has not personally felt Sinophobia on the rise in the US. Even if there's growing anti-Chinese sentiment, "Beijing is to be blamed," he said, adding: "Trump is only taking countermeasures."

Ding is likely to become a naturalised American citizen soon. He says, if he can cast a vote in 2020, he has found a fighter for his cause.

- Published17 June 2019

- Published6 April 2018

- Published7 May 2019

- Published21 October 2015

- Published1 April 2019

- Published23 June 2019