The 'code of silence' killing US police officers

- Published

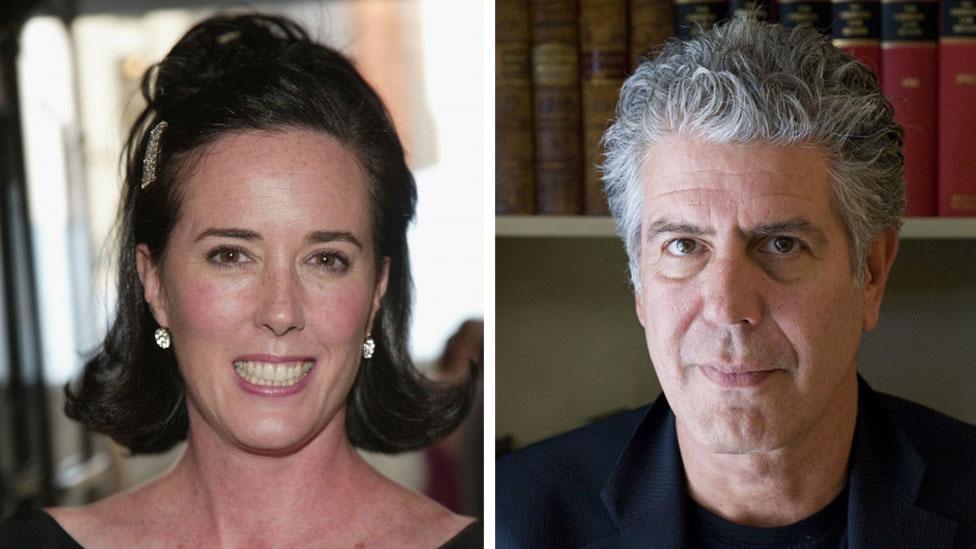

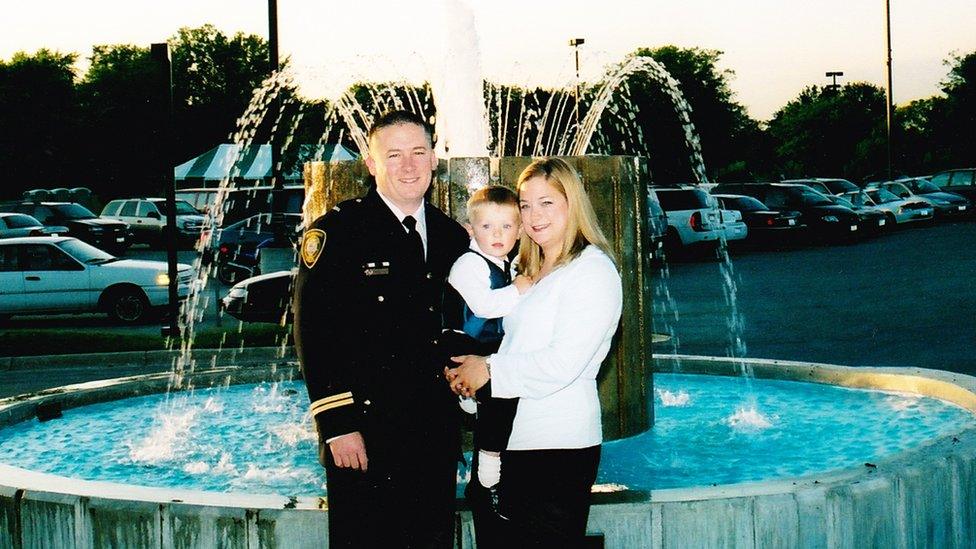

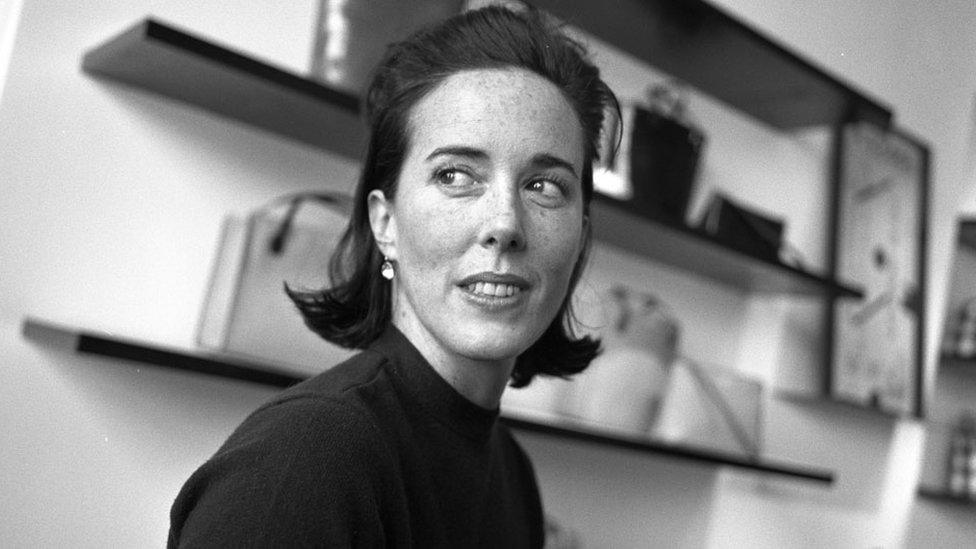

Dave Betz and his son David (left)

The death of nine New York police officers this year has left family members, law enforcement and politicians pointing fingers and placing blame. But suicide is a more profound problem, deeply entrenched in police culture. What's behind the epidemic?

Speeding down route 1 on a frigid, grey February morning, Dave Betz's heart was racing. As a hardnosed police officer of 32 years, he was used to car chases, but on this morning, he was a father searching for his son. Dave received a call earlier that morning at 09:21 that his 24-year-old son David, also a police officer, did not show up for his shift at work. Something didn't sound right.

After he hung up the phone, he opened the door to his son's room where he found a gun holster resting atop the bureau - its weapon missing.

"I'm calling my buddies, letting them know, 'listen this is not good. I don't have a good feeling about this at all.' You know, I had that pit in my stomach."

Charging across the empty car park of the Boston Sports Club, Dave noticed his son's Volkswagen, windows fogged, tucked in the distant corner behind the overbearing concrete gym building. As he walked around to the front of the car, his police training kicked in.

"That mindset of a cop - fight or flight - that kinda thing kicked in to react, like you're trained," he says.

"Death is not something that anybody likes to see. You just don't want to see it, you know. You do, but it's somebody else's family member.

"He was in his car, he was seated and he had his phone in his lap. And I knew, you know. I just didn't want to know," he says as his voice drops. He pauses.

Country music blared from the car radio as Dave, dressed in pyjama pants and a t-shirt, stood over his son and realised he was dead.

David Betz died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound without leaving any explanation of what led him to that moment, his father says. He's among hundreds of officers across the US who have taken their own lives and left behind a trail of questions.

"I always thought I was a good judge of character, being able to see things and see if somebody needs help or I should know when someone needs help," he says.

"I couldn't see it in my son, you know, so that bothers me."

Dave stands in the parking lot where he found his son while displaying a photo of them together

A 2018 nationwide study found more law enforcement officers died by suicide than in the line of duty. Researchers say that police officers are at a higher risk of suicide than in any other profession due to a combination of the intense stress, pressure to conceal emotional distress and easy access to deadly weapons.

In fact, 13 out of every 100,000 people die by suicide in the general population. But that number climbs to 17 out of 100,000 for police officers, according to the Ruderman Family Foundation.

Last year 167 police officers took their own lives while 130 have done so this year, with four months left on the calendar, according to Blue Help, a Massachusetts-based police suicide prevention group that tracks the national rate.

These numbers only reflect confirmed suicides. Some suicide prevention advocates say current estimates could be higher as some families choose not to report the cause of death or instead describe it as accidental.

An unspoken reality

New York City bears the brunt of most of the recent national attention. New York Police Department (NYPD) Commissioner James O'Neill declared a mental health crisis as the city grappled with the suicide deaths of nine police officers.

"We need to change the culture," he told reporters in June. "We need to make sure that our police officers have access to mental healthcare. So they can keep themselves well and do the job that they want to do."

But the crisis continued to cascade across the city.

Robert Echeverria, 56, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in August, just a day after 35-year-old Officer Johnny Rios took his own life.

His sister, Eileen Echeverria, told the BBC she contacted internal affairs about concerns for her brother's mental health numerous times, most recently in June before his death.

The department said it would investigate, but the 25-year police veteran's guns were returned to him within two days. She blames the top brass for his suicide.

New York City Police Commissioner James O'Neill

"The NYPD is broken on so many levels. It's not the same, officers used to be respected," she told the BBC before meeting the deputy commissioner of employee relations outside police headquarters in New York.

"Now they're spit on in the streets and then they come back to the chief and they're spit on by him. I couldn't go home and be normal after that. I couldn't do it. I'm not strong enough. God bless the ones who are."

The NYPD says Echeverria's death is under investigation.

"We need change," she says.

Cities and states across the country are rattled by a similar problem. California, Florida, New York and Texas each reported at least 10 police suicides last year, according to Blue Help.

Earlier this year, the Chicago Police Department, the nation's second largest force with 13,000 officers, was forced to confront its own spate of police suicides.

Tragedy sparked the launch of a mental health campaign, which included doubling the number of therapists available to officers as well as a video campaign showing senior officers - including Superintendent Eddie Johnson - admitting their own struggles with mental health.

President Donald Trump has authorised up to $7.5m (£6.1m) in grant funding a year for police suicide prevention, mental health screenings and training as departments across the country work to curb the numbers.

But the problem is hardly an American one. A similar trend is cropping up in other countries where officers are armed with a gun.

Last year France saw a 36% higher rate of suicide among police than the general population, and this year 64 officers have already taken their own lives.

For comparison, about 21 to 23 officers took their own lives in the UK between 2015-17, according to the UK's Office for National Statistics. Unlike France, most British police do not carry guns.

Nearly two-thirds of all gun deaths in the US are suicides, according to data compiled by Everytown, a gun safety group.

Though people are less likely to attempt suicide with a gun (6% of all attempts), the nature of the deadly weapons makes death more likely, with about half of all suicide deaths involving a firearm.

At least six of the nine deaths in the NYPD involved a gun, with many using their own service weapon.

Why is suicide so high among police?

John Violanti, a 23-year police veteran and professor at University at Buffalo who focuses on police stress and mental health, points to the nature of the job as part of the equation that leads to suicide.

"They see abused kids, they see dead bodies, they see horrible traffic accidents. And what that means is that the traumatic events and stressful events kind of build on one another."

"If you have to put a bulletproof vest on before you go to work, that's an indication you're already under the possibility of being shot or killed and your family is under the same probability. So all of these things weigh heavily on the psyche and over time, they hurt the officers."

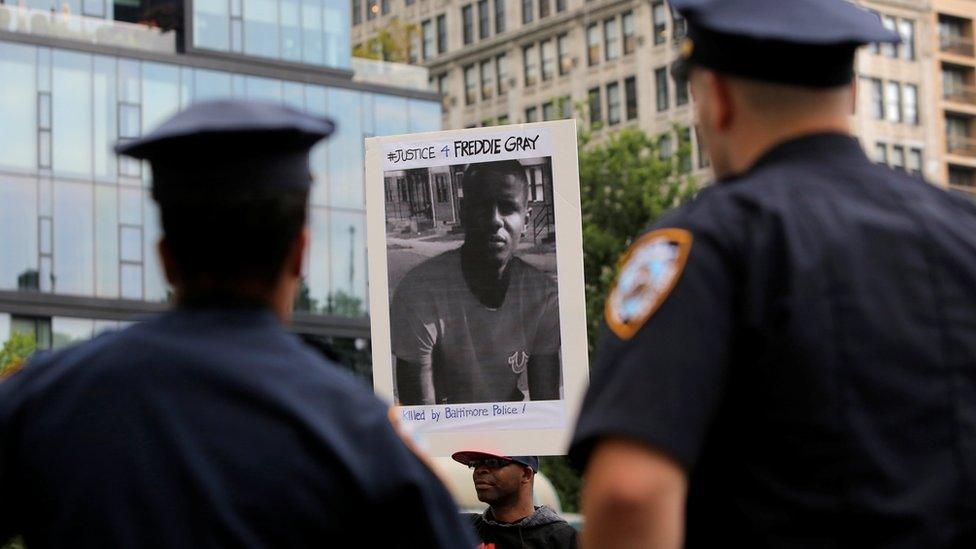

He also points to an increasing turmoil driving a wedge between law enforcement and the communities they protect.

"We have political conflict. We have societal conflict. We have groups at each other's throat all the time. And the cops get stuck in the middle of all of this stuff," he says. "So sometimes they're pulled in different directions and they really don't know what their role is."

More voices on these issues

Mark DiBona, a 33-year police veteran and spokesman for Blue Help, has firsthand experience of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on the job.

He volunteered for three weeks in New York four days after the 9/11 attacks and recalls his nightmares began shortly after. That trauma compounded with other encounters, including responding to a car fire with a passenger trapped inside, led to his depression.

"I wanted to die. I just did not want to go further because I felt like a failure," he says.

Sitting in the front seat of his cruiser, Mark wrote an angry letter to the police department and an apology letter to his mother and wife, before placing his gun in mouth.

In a fortuitous moment, another officer pulled up to his car to intervene before he pulled the trigger.

But he - along with many officers - believes one of the greatest barriers in seeking help is the stigma that comes with needing it.

"We carry a gun, we carry a Taser, we carry a baton, Mace, we wear a bulletproof vest. All that to protect ourselves physically," he says.

"We need that. But we have very little training when it comes to protecting us mentally."

Part of that stigma is perpetuating the machismo culture in police work, a notion that Janice McCarthy is working to change by training officers in suicide prevention and through her organisation Care of Police Suicide Survivors (Copss), which works with families affected by police suicides.

Janice's husband Paul killed himself in July 2006 after a 21-year career as a Massachusetts state police captain. He suffered PTSD that stemmed from three car accidents in the line of duty, she says.

Janice McCarthy has spent the last 13 years after her husband's death pushing for mental health training in law enforcement

"Hypervigilance" is part of the job when it comes to police work, Janice says. "It's that feeling you're jumping out of your skin, you're pacing back and forth.

"Cops run on the adrenaline…it becomes almost like a high," she recalls of her husband. "But the problem is you can't come home and shut it off and [Paul] could not shut it off. He didn't sleep. He couldn't really have a conversation," she recalls.

"They are caretakers. They are used to taking care of everyone else.

"He would change flat tyres, he saved premature newborn babies. He couldn't save himself because no one gave him the luxury to say, 'what's wrong? Are you OK?'"

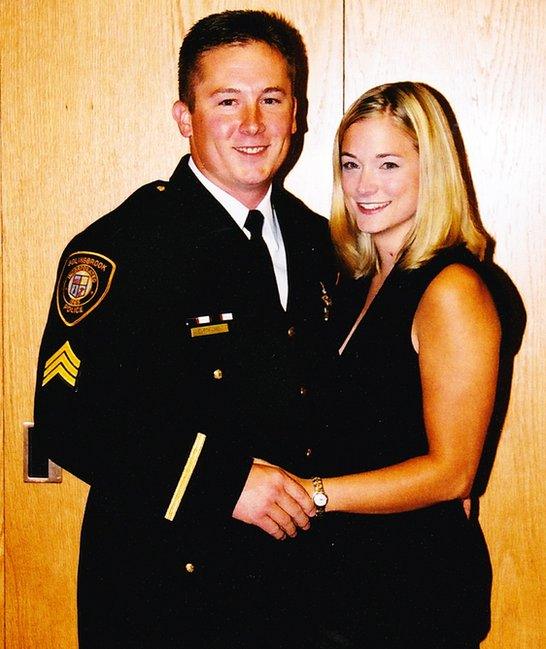

Paul McCarthy, Janice's husband, and their son Christopher

She helped lawmakers in Massachusetts craft a bill that would mandate mental health training for officers on the job. The bill, four years in the making, has yet to be taken up.

But former officers and suicide prevention advocates say adding therapists and training is only part of the battle.

The fear of losing your gun

The idea that an officer's identity is tied to their gun is a stigma advocates can't seem to crack.

"The one thing about law enforcement is the longer you're on the job, the more it consumes your identity," Mark says while describing the importance of an officer's badge and gun.

Chris Prochut was third in command in Bolingbrook, a south-west suburb outside of Chicago, when his police department received international attention about a high profile murder investigation within its ranks.

He was tasked with dealing with the drumbeat of reporters, clamouring for details about former Sgt Drew Peterson, who was accused of murdering his third and fourth wives, the latter of whom is still missing.

"I thought I can handle this because that's what cops do. I can fix this," the now mental health advocate and suicide prevention trainer recalls. "I figured I could change the public perception of our police department."

Under immense pressure and with little sleep, the case ate away at Chris' psyche, taking a toll as the year wore on.

Chris Prochut planned his own suicide before his wife and colleagues thwarted his plan

"I'd come home to my family and I didn't want to be around them," he recalls.

At the urging of his wife, Chris sought help, and eventually went on medication to help ease the anguish. But the pain didn't stop. He eventually decided to take his own life.

"In my mind there was no other option because I had tried therapy. I tried medication. They don't work for me, but I can get a hold of this."

He chose a wooded area where he wanted to take his life in a nearby town, a deliberate move so his colleagues wouldn't have to investigate the death of one of their own.

"The plan was set. I remember having an extra bounce in my step that week."

It was ultimately his wife who thwarted his plans, calling his colleagues to intervene in the middle of the night and escort him to hospital to seek psychiatric treatment.

After Chris was released from hospital, Illinois state law mandated that he lost his firearm privileges, and stuck in a legal loophole, he eventually lost his job.

Chris and his family left Illinois after losing their house, relocating to Hartford, Wisconsin, where he now works at Kohl's corporate headquarters as well as with the state police on suicide prevention.

The laws have since changed in Illinois, allowing gun owners a 60-day grace period to keep their Firearms Owners Identification Card while a renewal application is processed. Part of that aim is to encourage officers to seek mental health treatment without fear of losing their badge - a step Chris is hopeful could be emulated elsewhere.

But Chris also wants his story to show there is life after the force.

"It took me a couple of years to realise there is life after law enforcement but you gotta be here. You have to be here in order for it to get better," he says.

"I did get my gun taken and I did lose my job, but I'm here and I'm OK."

Life continues

Back at the cemetery on Boston's North Shore in Lynn, Dave's youngest son, Cameron, idles near David's grave, his voice cracking as he struggles to talk about his brother, his hero.

Cameron is adorned in symbols honouring his brother - suicide prevention bracelets and a tattooed semicolon on his left wrist - a symbol used to raise awareness about mental health struggles and suicide prevention - to show that life continues.

"Life for them goes on. Life for us goes on in a different kind of way," Dave says of other police officers.

Much of Dave's life is also a memorial to his son. His office is canvassed with images of his eldest son and the rest of his family, alongside relics and mementos featuring hidden symbols to keep David's memory alive.

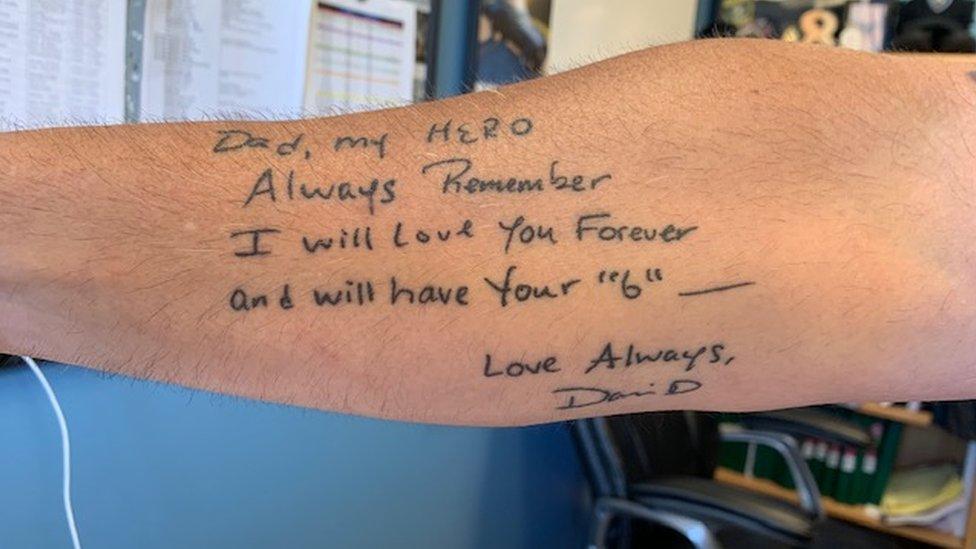

An image of clouds over his son's grave, formed in the shape of the number eight - David's lucky number - sits framed next to his son's police boots and uniform. His arms are tattooed with his son's favourite number and a message on his forearm, scrawled in David's handwriting, from a Father's Day card given to him in June, before he passed away.

Dave Betz displays his arm, revealing his tattoo of a Father's Day message written by his son

Death by suicide can erode validation for loved ones and family members, leaving unanswered questions of what could have gone differently to avoid tragedy.

"Being a suicide survivor - it's a group we belong to and we never wanted to be," Janice says.

"If someone dies by suicide, there are a whole lot of things that people read into that everyone wants to have their own idea of what went wrong. It's human nature to try to figure something out and put it in that nice little box and put a bow on it and put it away."

But for this group of survivors, speaking to officers is a way of filling that void left by those they lost to suicide.

For officers concealing their struggles, Janice has one message: "If you're not a cop tomorrow, who are you?

"Well, are you a husband? Are you a father? You need to be multidimensional and you need to take care of yourself emotionally," she declares.

"I would want them to know that they are more than a police officer and that their life means more than this job."

Where to get help

From Canada or US: If you're in an emergency, please call 911

You can contact the US National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 1-800-273-8255 or the Crisis Test Line by texting HOME to 741741

Young people in need of help can call Kids Help Phone on 1-800-668-6868

If you are in the UK, you can call the Samaritans on 116123

For support and more information on emotional distress, click here.

- Published5 August 2019

- Published18 July 2016

- Published11 July 2016

- Published7 June 2018

- Published11 June 2018