Maxime Bernier: Can populism become popular in Canada?

- Published

Maxime Bernier has quit the Conservative Party of Canada, months after losing its leadership race

A new political party in Canada hopes to capitalise on the global rise of populism during this autumn's election. But can the People's Party get people's attention?

Around the world, voters have chosen what political scientists call "populism" - a rejection of the established order and so-called "elites".

It happened in the US with Donald Trump, and in Brazil with Jair Bolsonaro. Some would argue that Brexit, and the triumph of Boris Johnson during the Conservative leadership race, would also fit the definition.

On the left, Bernie Sanders has been labelled populist for shaking up the old guard in the Democratic Party.

While the traditional political order has undergone an enormous upheaval around the globe, Canada has been something of a steady eddy since the election of Justin Trudeau in 2015.

But a new political party in Canada hopes to change that.

The People's Party of Canada was formed last summer, when MP Maxime Bernier quit the Conservative Party after a fallout over statements he made online about immigration and multiculturalism.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"I have come to realise over the past year that this party is too intellectually and morally corrupt to be reformed," Mr Bernier said at the time.

Who is Maxime Bernier?

Mr Bernier was elected to parliament in 2006 for the district of Beauce, Quebec - the same district once held by his father Gilles Bernier, a radio DJ-turned politician.

Back then, Mr Bernier made waves for himself as a "freethinker" not afraid to challenge some of the Conservative Party's sacred cows, like supply management in the dairy industry. The long-running scheme provides dairy farmers with a guaranteed price for milk, but runs counter to Mr Bernier's small-government ideals.

"It was clear he was not afraid to break rank with the Conservatives on occasion - he was a bit of a maverick," says Martin Croteau, a reporter for La Presse who covered Mr Bernier for several years.

It made him a hero in Canada's libertarian west.

But he also had his share of scandals, most notably involving his ex-girlfriend, who was once married to a member of a biker gang. In 2008, he was forced to resign from cabinet because she revealed in a television interview that he once left a secret government document at her house.

"It did not make him look like a professional," Mr Croteau says.

"Long time ago" - Canadians react to Trudeau brownface images

He bounced back, and by 2016 he was the frontrunner at the Conservative leadership convention.

But he lost the leadership by a hair to Andrew Scheer, who had support from the dairy lobby. He soon fell out with the party, and by the summer of 2018 and he was determined to strike out on his own.

Now just weeks before the People's Party heads to its first general election, polls suggest the party has a shot at winning some select ridings, external. The race is close enough in these ridings that Mr Bernier has been invited to participate in the leaders' debates on 7 and 10 October, which lends the party some credibility.

But Mr Bernier doesn't need to win a government - or even a seat - if he wants to hurt his one-time rival Mr Scheer. All he has to do is slice off enough of the right to prevent the Tories from winning their seats.

A populism contest?

The People's Party has been adept at grabbing headlines - such as when he called teen climate activist Greta Thunberg "mentally unstable", or when he spoke in support of billboards erected by a third-party organisation promoting the party, with the slogan "Say no to mass immigration".

This kind of anti-progressive, anti-immigrant rhetoric could be a page out of Donald Trump's playbook. But former Conservative MP Peter MacKay says he never thought of Mr Bernier as a "populist".

"My memories of him, and my observations, were more that he fit into the category of libertarian," he says. The two worked together in the cabinet of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, before Mr MacKay left politics in 2015.

"But these hot-button issues that I think can be characterised as populist, such as immigration and some social issues, I think there is an element of opportunism."

Concern about immigration is growing in Canada, in part due to an increase of refugees at the US-Canada border. A June Leger poll found that two-thirds of Canadians think that immigration should be limited.

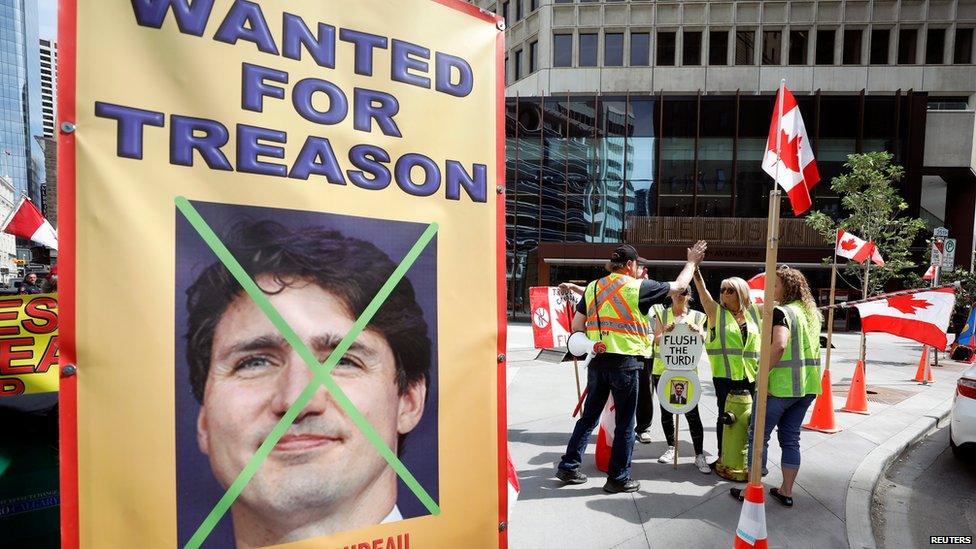

Yellow vest protesters demonstrate outside a Liberal Party fundraiser

This is quite the change for Canada, says Eric Kauffman, who teaches politics at Birkbeck University of London. "There's a stronger set of taboos and political correctness around issues like immigration," he says.

Mr Kauffman believes that Canada's multicultural identity has kept right-wing populism from gaining a foothold in most parts of the country.

But there are signs the mood is changing, he says, with voters in Quebec and Ontario electing populist-style premiers.

Quebec Premier François Legault, who leads the Coalition Avenir Québec, was elected on a platform that promised to limit immigration and ban religious symbols like Muslim headscarves and Jewish yarmulkes.

In Ontario, Conservative Premier Doug Ford railed against the "downtown elites" and opposed funding services for refugees who crossed the border. The anti-elite, anti-immigrant yellow vest movement, which began in France, has also found a home in Canada's oil patch, where many people are out of work.

But in order for right-wing populism to take off in Canada, voters would have to reject the Conservative Party. So far, they haven't.

Only 3% of Canadians would like to see Mr Bernier become prime minister, according to a Nanos Research poll of 1200 respondents (margin of error ±2.8 percentage points) on 23 September. About 34% would like to see Mr Scheer elected.

But experts used to say populism could not happen in the UK or Germany, Prof Kauffman says, and populist movements in the form of Brexit and the Alternative for Germany party have taken off.

"All of these exceptions have fallen one by one," he says.

- Published28 May 2017