Jody Wilson-Raybould: The woman who fought Justin Trudeau

- Published

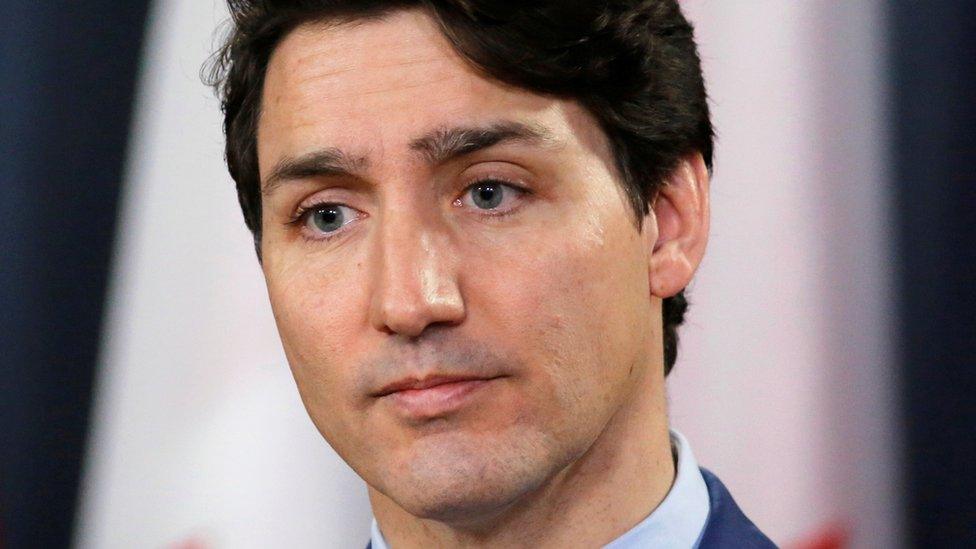

Wilson-Raybould has been a thorn in Trudeau's side

Canadian MP Jody Wilson-Raybould was booted from the Liberal Party by Justin Trudeau. Could she be the one to take him down?

If Jody Wilson-Raybould had her own walk-up song, like major league baseball athletes, then surely Destiny's Child's Independent Woman would play every time she went up to bat.

The 48-year-old MP is running as an independent in the upcoming election, having been kicked out of the Liberal Party by Mr Trudeau for going public with her complaints about how he tried to pressure her to cut a deal with Quebec company SNC Lavalin.

Although she was courted by several other parties, she says she ultimately decided to go it alone as an independent so that she could get away from the "hyper-partisan" politics of Parliament Hill.

"We need to, as much as we can, take off our partisan hats and have discussions about issues," she tells the BBC.

Looking back, Canada's first indigenous attorney general says she "never expected" to be in this position, but that she would not change her actions.

"I think it was an unfortunate decision on his part, but I'm embracing the reality of being an independent candidate," she says.

Explaining the Trudeau crisis to a Trump reporter

Now Ms Wilson-Raybould could play a deciding role in the Liberal Party's fate when Canadians head to the polls on 21 October. Since being booted from caucus, she has become a symbol for Mr Trudeau's perceived weaknesses - his ties to corporate interests, his superficiality when it comes to feminist and indigenous issues, and his heavy-handedness as a party leader.

Fallout from the SNC Lavalin affair, as well as the Liberal's environmental record, have chipped away at the party's support in the city of Vancouver, where her riding (district) of Vancouver-Granville is located.

She won her race handily in 2015 as a Liberal, beating the runner-up New Democratic Party (NDP) candidate - Canada's left-leaning party - by 17 points. If she wins again as an independent, that will be one less seat the Liberals take to parliament, and polls show they don't have many they can afford to lose if they want to hold onto power.

Although she doesn't have the Liberal's big election machine to back her up this time around, she says being independent has its advantages because it frees her from partisan showboating and allows her to work with whoever has the best proposal for Canadians.

"No party has a monopoly on the truth, and certainly no party has all of the solutions to the issues we're facing as a country," she says.

"Long time ago" - Canadians react to Trudeau brownface images

Leaving the Liberal Party has also allowed her to comment freely on Mr Trudeau's other scandal, the release of photos showing him wearing blackface before he was elected to parliament.

"I do not believe there's any place for people who are entrusted with the public trust, or in positions of power and authority to engage in activity like that," she says.

Born to a political family, her father Bill Wilson was a hereditary chief and an important campaigner for indigenous rights in Canada.

In 1983, he told Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau - Justin Trudeau's father - that he had two daughters who both wanted to be lawyers and one day prime minister.

His statement would prove prophetic. She studied law at her father's alma mater, the University of British Columbia. She worked as a Crown prosecutor, then became involved in indigenous politics, and was elected regional chief of the BC Assembly of First Nations in 2009.

In 2015, the Liberal Party tapped her to run in the federal election for the riding of Vancouver-Granville. She won her seat and was appointed by Mr Trudeau to become Canada's first indigenous justice minister and attorney general (one person has both roles in Canada, unlike in the UK).

As attorney general, she helped usher in landmark legislation, including legalising cannabis and assisted dying. She was often pointed to in the press as an example of Mr Trudeau's modern, feminist approach to politics.

During the height of the SNC scandal, she was under siege from the press

But Ms Wilson-Raybould found herself under a different kind of spotlight last February, when the Globe and Mail newspaper reported on a falling out between her and Mr Trudeau over her decision to prosecute SNC Lavalin.

The Quebec firm was accused of bribing officials in Libya to win contracts under Muammar Gaddafi's regime. It had been lobbying the government for a deal that would avoid prosecution.

Ms Wilson-Raybould says she was subjected to mounting pressure from the government to cut the deal, which would have gone against the advice of her legal staff. Mr Trudeau says he was concerned that if SNC Lavalin went to court, they'd pull out of Quebec and it would cost thousands of jobs.

In January, amid a cabinet shuffle, she was moved out of the justice ministry and given the job of minister of veteran's affairs, a role she and many others viewed as a demotion. Mr Trudeau denied it was retaliation.

Soon after, she resigned from cabinet, as did her friend MP Jane Philpott, who said "there can be a cost to acting on one's principles, but there is a bigger cost to abandoning them". In response, Mr Trudeau ejected them both from the Liberal caucus, accusing them of not being team players.

Jane Philpott (left) quit cabinet along with Wilson-Raybould (right), now both independents

Ms Wilson-Raybould says she was vindicated in August, when the ethics commissioner found that Mr Trudeau "used his position of authority over Ms Wilson‑Raybould to seek to influence, both directly and indirectly, her decision", which violated ethics rules.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police have said they are reviewing the SNC Lavalin affair to see if further criminal proceedings are required.

Although widespread coverage of the scandal initially hurt Mr Trudeau in the polls, he has since rebounded.

Asked as to how her own personal opinion of the prime minister has changed, Ms Wilson-Raybould prefers to demur.

She says she may talk about it publicly one day, but for now, she just has the election on her mind.

"I'm in the place where I need to be. And the prime minister is running for his riding, and will have to ensure that he can look himself in the mirror at the end of the day, which we all have to do."

- Published14 August 2019

- Published3 April 2019

- Published6 November 2015

- Published19 September 2019