Trump impeachment: White House aides can be made to testify

- Published

Don McGahn must testify in the impeachment inquiry, a judge has ruled

A federal judge has ruled that White House staff can be made to testify before Congress, rejecting the Trump administration's claims of immunity.

The ruling specifically compels former White House counsel Don McGahn to testify to an inquiry into Russian interference in the 2016 US election.

But it also has major implications for the Democrat-led impeachment inquiry against President Donald Trump.

The justice department says it will appeal against the ruling.

The impeachment inquiry is trying to establish whether Mr Trump pressured Ukraine's president to investigate his political rival Joe Biden. The Trump administration has refused to co-operate with the impeachment inquiry and other Democrat-led investigations, directing current and former White House officials to defy subpoenas for testimony and documents.

Mr McGahn, who left his post in October 2018, was called to appear before the House Judiciary Committee in May to answer questions about the president's alleged attempts to impede the now-concluded Mueller investigation into Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election.

But in her ruling, US District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson said that "no one is above the law".

What does it take to impeach a president?

"Executive branch officials are not absolutely immune from compulsory congressional process - no matter how many times the executive branch has asserted as much over the years - even if the president expressly directs such officials' noncompliance," she wrote.

Judge Jackson also explicitly said the president "does not have the power" to stop his aides from responding to subpoenas from Congress - adding that "presidents are not kings".

"No one, not even the head of the Executive branch, is above the law," Judge Jackson said.

But she did say that Mr McGahn could invoke executive privilege "where appropriate", to protect potentially sensitive information.

Judiciary Committee chairman Jerrold Nadler said that he expects Mr McGahn to "follow his legal obligations and promptly appear before the Committee".

What are the legal implications?

By Jonathan Turley, law professor at George Washington University

"Presidents are not kings." Those words from a 120-page decision by US District Court Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson are likely to be repeated like a mantra by Democrats in Congress. With members seeking to impeach President Trump for obstructing their impeachment inquiry by blocking witnesses and discovery, the timing and language of the opinion could not have been better.

Ms Jackson at times allowed the rhetoric to outpace the analysis in declaring, for example, that "presidents are not kings" and "this means that they do not have subjects, bound by loyalty or blood, whose destiny they are entitled to control. Rather, in this land of liberty, it is indisputable that current and former employees of the White House work for the people of the United States..."

I am not sure that seeking review on a claim of immunity is the same as a president declaring oneself king or former presidential aides effective vassals.

However, while Republicans are attacking Jackson as a liberal Obama appointee, the ultimate holding is clearly correct. I have written previously that the White House was wrong in claiming that it can block even the appearance of such witnesses - as opposed to allowing an appearance while instructing the witness not to answer certain questions on privileged matter. It is the difference between immunity and privilege.

Nevertheless, I fail to see the good-faith basis for the extreme position stated by the White House - a criticism that I have had with a number of current cases moving through the courts. These cases seem crafted with a greater interest in the ultimate delay rather than the decision in the litigation. That strategy however continues to pile up losses for the White House - precedent that will bind future presidents.

Jonathan Turley is a legal analyst for the BBC. He testified as a constitutional expert during the Clinton impeachment.

Why is Congress investigating Trump?

Monday's ruling could have an effect on who testifies during the current impeachment hearings in Congress.

Democrats may use it to summon figures such as former National Security Adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

The impeachment case centres on whether President Trump used the threat of withholding US military aid to pressure Ukraine into investigating a domestic political rival.

At the heart of the impeachment inquiry is a phone call on 25 July this year between Mr Trump and Ukraine's newly elected president, Volodymyr Zelensky.

A phone call between Presidents Trump and Zelensky is at the centre of the impeachment inquiry

During the call, Mr Trump urged his counterpart to look into unsubstantiated corruption claims against Democratic White House contender Joe Biden.

Mr Trump's critics say this alleged political pressure on a vulnerable US ally amounted to abuse of power.

The president has denied any wrongdoing and has called the inquiry a "witch hunt".

What next with the impeachment inquiry?

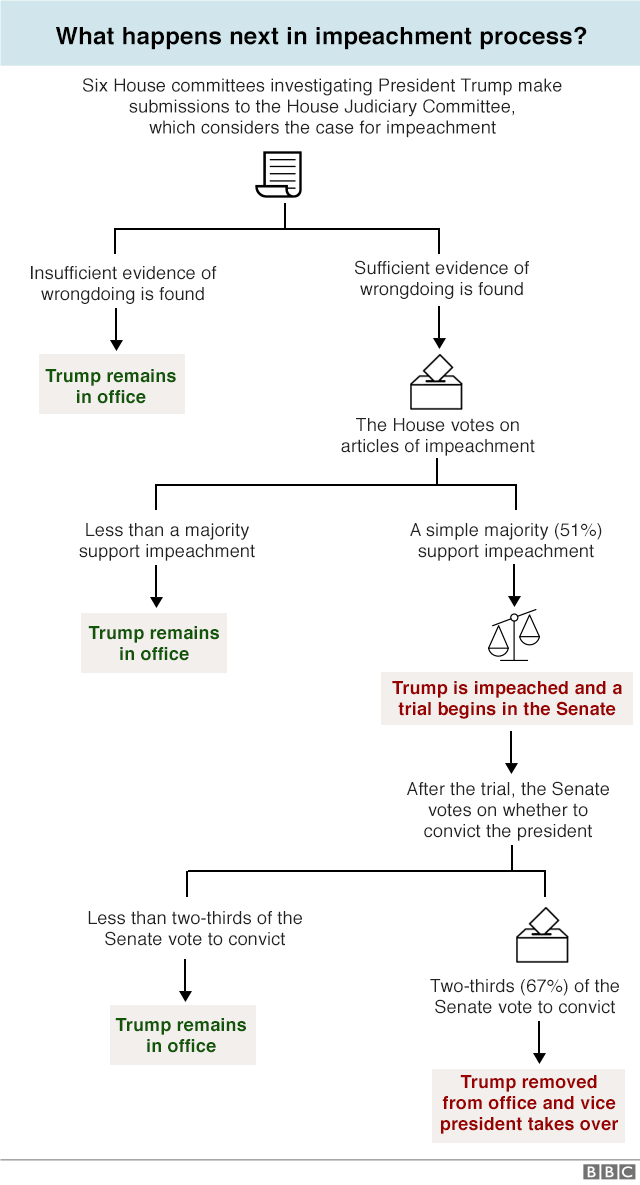

The Judiciary Committee is expected to begin drafting articles of impeachment - which are the charges of wrongdoing against the president - in early December.

After a vote in the Democratic-controlled House, a trial would be held in the Republican-run Senate.

If Mr Trump was convicted by a two-thirds majority - an outcome deemed highly unlikely - he would become the first US president to be removed from office through impeachment.

The White House and some Republicans want the trial to be limited to two weeks.

Learn more about the impeachment inquiry

GO DEEPER: Here's a 100, 300 and 800-word summary of the story

WHAT'S IMPEACHMENT? A political process to remove a president

VIEW FROM TRUMP COUNTRY: Hear from residents of a West Virginia town

ON THE DOORSTEP: A Democrat sells impeachment to voters

- Published19 December 2019

- Published5 February 2020

- Published21 May 2019