Trump impeachment trial: What you might have missed

- Published

Schiff: 'The facts are damning'

The impeachment trial of President Donald Trump is hurtling towards its conclusion as senators prepare to cast their final vote on Wednesday, with acquittal almost certain.

Democratic hopes were dealt a blow last Friday when senators voted against introducing new witnesses to the trial.

As prosecutors in the trial, Democrats had laid out meticulous evidence over three days that they said proved Mr Trump had abused his power and obstructed Congress.

They alleged that he pressured Ukraine to dig up political dirt on Joe Biden, a domestic rival, and that he sought to hide the evidence from Congress, another impeachable offence.

The White House lawyers, on the other hand, argued Mr Trump had done "nothing wrong" and that the president has not committed offences that would warrant his removal.

President Trump and senior Republicans claim Mr Biden and his son Hunter were involved in a corrupt business scheme in Ukraine.

Here's a look back at what happened over the course of two weeks.

The closing arguments

Democratic House managers:

said senators had a duty to remove President Trump from office

"He has betrayed our national security, and he will do so again," said Adam Schiff

"Truth matters to you. Right matters to you. You are decent. He is not who you are."

White House lawyers:

argued that it should be up the voters to decide the president's future, not Congress

said this was the most "partisan" impeachment in history

"They have cheapened the awesome power of impeachment," said Jay Sekulow.

How the prosecution case unfolded

Proceedings began on 21 January with a tussle between Democrats and Republicans over the rules of the trial.

Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell proposed a tight two-day limit for opening arguments by both sides, before extending it to three after protests from Democrats.

Mr McConnell delayed debate over motions from Democrats to allow new witnesses to be called and fresh evidence submitted.

Democratic congressman Adam Schiff, the head of seven impeachment managers who serve as prosecutors, opened oral arguments to a packed Senate chamber on 22 January.

Mr Schiff said the president's actions were exactly what the Founding Fathers feared when they came up with impeachment - "a remedy as powerful as the evil it was meant to combat", Mr Schiff said.

A beginner's guide to impeachment and Trump

The impeachment managers walked the senators through testimony gathered during depositions and committee hearings last year that they say points to a scheme by Mr Trump and his advisers to lean on Ukraine to investigate the Bidens.

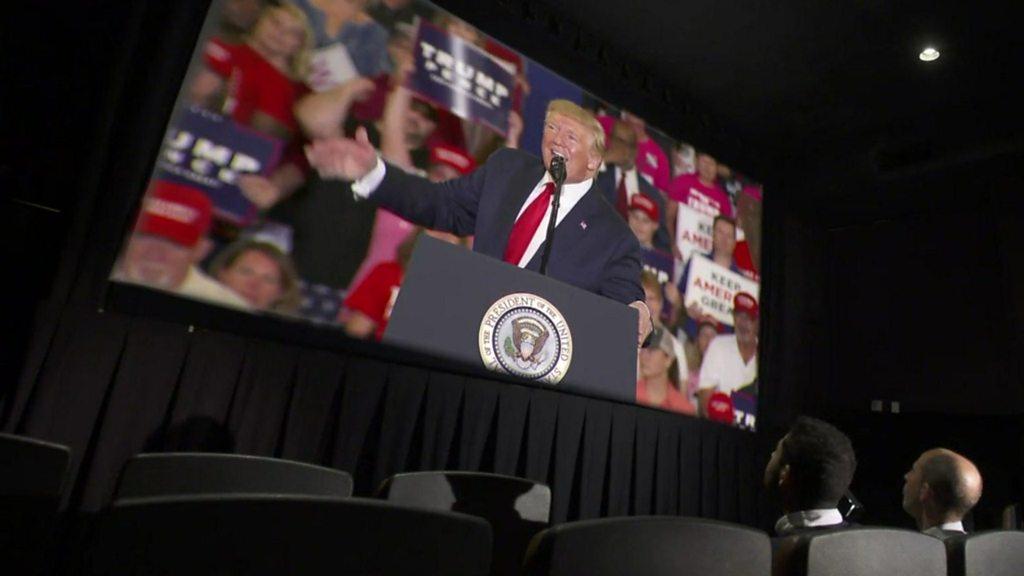

The managers interspersed their oral arguments with audio and video tape, using the president's own words - including a now-infamous call with the president of Ukraine - in their effort to portray him as guilty.

They directly addressed the claims against the Bidens - a purposeful attempt to get on the front foot ahead of the president's defence.

The managers then tackled the obstruction of Congress charge.

The managers argued that Mr Trump's refusal to allow certain members of his administration to answer questions from the House of Representatives was akin to hiding information from a grand jury investigation.

How the defence unfolded

During opening arguments, Mr Trump's team took barely two hours to argue that the president had done nothing wrong.

His team insisted that Mr Trump had acted in the national interests in his phone call with the Ukrainian president, with Deputy White House Counsel Mike Purpura pinpointing a line from the transcript in which Mr Trump asked Volodymyr Zelensky to "do us a favour", rather than "me".

Mr Purpura also insisted there was no quid pro quo, saying Mr Zelensky "says he felt no pressure".

The defence accused the Democrats of trying to remove Mr Trump from the ballot this year, and said the American electorate should be allowed to decide for themselves.

Resuming arguments on 27 January, attorney Kenneth Starr warned senators that impeachment could become "normalised" and used as a weapon against future administrations.

Mr Starr came to prominence in 1998, when he led an investigation into Democratic President Bill Clinton that laid the foundation for his impeachment.

"Like war, impeachment is hell," Mr Starr said on Monday. "It's filled with acrimony and divides the country like nothing else. Those of us who lived through the Clinton impeachment understand that in a deep and personal way."

Following Mr Starr, Trump defence lawyer Jane Raskin addressed Rudy Giuliani - Mr Trump's personal attorney and a central character in the impeachment case.

"Mr Giuliani was not on a political errand," she said, referring to his investigations in Ukraine.

Sondland was involved in a "domestic political errand" for Trump

"Rudy Giuliani is the House managers' colourful distraction," Ms Raskin said - a way for the Democratic impeachment managers, who act as prosecutors, to divert attention from weaknesses in their case.

What happened during questioning?

On 29 January, senators began a period of questioning after opening arguments concluded.

Over two days and 16 hours on the floor, they submitted over 100 queries written on cards to Chief Justice John Roberts, who read them to the House managers and defence.

The justice was firm about keeping time, limiting answers to five minutes.

Questions alternated between Republicans and Democrats as lawmakers had their first chance to push back against claims made by both sides. A few queries were bipartisan.

Senators were not, however, allowed to address each other in their questioning.

The queries came amid a contentious debate over whether or not witnesses should be allowed in the trial - a matter that comes to a vote on Friday.

One submission was blocked by the Chief Justice: Republican Rand Paul's question that included the name of a person believed to be the whistleblower that sparked the entire impeachment inquiry was rejected.

Other questions, including when the president ordered the aid hold on Ukraine and whether Mr Trump ever mentioned the Bidens prior to Joe Biden entering the 2020 race, were not fully answered.

On Friday, the trial moves into four hours of debate over whether new witnesses and documents should be permitted.

- Published23 January 2020

- Published22 January 2020

- Published1 February 2020

- Published21 January 2020

- Published22 January 2020