Viewpoint: In this impeachment, people only heard what they wanted to

- Published

Mitch McConnell blocked witnesses at the trial and Nancy Pelosi said it wasn't a real acquittal

Another rancorous presidential impeachment trial has ended in acquittal. What are the key things we learnt, asks Jonathan Turley, a professor of law at George Washington University.

The predictable conclusion to the Trump impeachment leaves the trial as the perfect embodiment of our times - reason found little space in a Senate chamber filled with rage.

Trials often reflect societies and times - captured by jurors selected from the surrounding community. It is not surprising therefore that a jury composed of political representatives should perfectly mirror our politics.

What we saw was hardly flattering for either side. One of the most striking aspects is that it really did not matter what people actually said whether it was witnesses or the accused or even the Framers (the people who drafted the US Constitution).

It was the first entirely dubbed trial where advocates simply supplied the words that fit with their case rather than reality.

I personally watched this phenomenon firsthand as my own views were presented in highly tailored fashion by both sides. It included on videotape played by the House managers showing my rejection of the theory, advanced by one of the White House lawyers, Professor Alan Dershowitz, that crimes are needed for impeachments.

The edited tape cut off just before I said that, while you can impeach for just abuse of power, it is exceedingly difficult. It did not matter.

Constitutional expert Jonathan Turley testifies in the House impeachment probe in December

It also did not matter what President Donald Trump himself may have said.

The Republican majority in the Senate was not interested in hearing from National Security Adviser John Bolton, who reportedly was prepared to say that the president lied in denying that he connected the Ukrainian aid to an investigation of Bidens.

Indeed, while news reports recounted what Bolton said in his book, the White House said that it was merely hearsay since he did not say it directly. It then opposed any effort for him to say it directly as a witness.

In the end, however, it did not matter what any witness might say on that or other subjects. Their testimony was presumed and many senators declared that, even if they said something against the president, it would not matter.

That is the real takeaway. It really did not matter what anyone had to say.

Trump weathered the storm of impeachment and is job approval numbers are at an all-time high

It did not even matter what the Framers said, even when they were being cited for what they said.

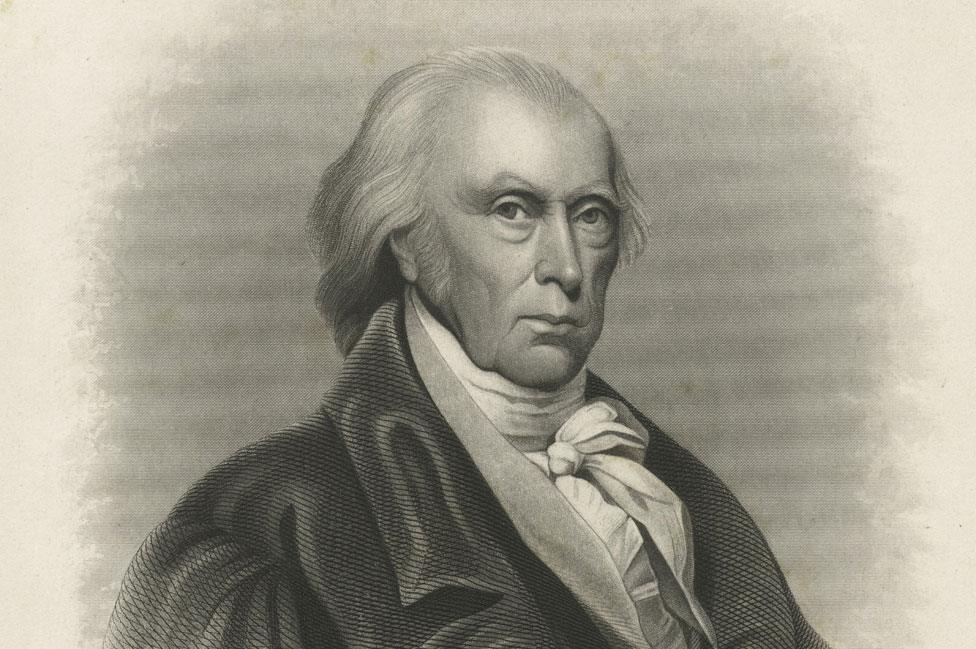

As a Madisonian scholar, I was particularly aggrieved to see Founding Father James Madison used like a marionette to either vilify or vindicate the president.

The most maddening were the references by Dershowitz, who argued that Madison clearly indicated that a non-criminal act could not be an impeachable offence.

It did not matter that Madison said the opposite. He not only referred to such non-criminal allegations as "the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief Magistrate", but the "loss of capacity or corruption" that "might be fatal to the Republic".

Moreover, in a letter in June 1833, he wrote to Senator Henry Clay over the withholding of a land act as a type of pocket veto. Madison assured him "an abuse on the part of the President, with a view sufficiently manifest, in a case of sufficient magnitude, to deprive Congress of the opportunity of overruling objections to their bills, might doubtless be a ground for impeachment".

That is precisely the type of non-criminal conflict that Dershowitz claimed could not be impeachable. But it did not matter. Those were Madison's view of Madison, not ours.

James Madison mentioned abuse of power as grounds for impeachment

I wrote once that Senate trials are always about the senators, not the accused. By extension, they are also about us. This country remains divided right down the middle on Donald Trump.

The trial was like watching a movie where the audience heard only the lines that they came to hear. Indeed, studies indicate that this may be hardwired with people subconsciously tailoring facts to fit their preferences.

Researchers at Ohio State University have found that people tend to misremember numbers to match their own beliefs. They think that they are basing their views on hard data when they are actually subconsciously tailoring that data to fit their biases. In other words, people selectively hear only one side even when being given opposing evidence.

People today receive their news in news silos, cable programming that reassuringly offers only one side of the news. This "echo-journalism" is based on offering a single narrative without the distraction of contradiction.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell accused Democrats of overturning the election result

Recently, MSNBC host Lawrence O'Donnell declared that his show will not allow Trump supporters on as guests because all Trump supporters are "liars". Likewise, Trump recently denounced Fox for even interviewing Democratic senators. When that is the state of our news, why should trials be any different?

In our hardened political silos, even Framers are bit players in a crushingly formulaic play. Witnesses are as immaterial as facts when the public demands the same predictability from politicians that they do from cable hosts.

We are all to blame. Politicians achieve their offices by saying what voters want to hear and today voters have little tolerance for hearing anything that contradicts their preset views of Trump.

As a result, the trial was pre-packed by popular demand. Speaker Nancy Pelosi even declared that Trump would "not be acquitted" even if he was acquitted. When the actual vote doesn't matter, why should the actual testimony?

Just as voters get the government that they deserve, they also get the impeachment trials that they demand. Watching on their favourite biased cable networks, voters raged at the bias of the opposing side in the impeachment as refusing to see the truth.

The Senate has voted in favour of acquitting President Trump on the impeachment charges

Viewers thrilled as their side denounced their opponents and hissed when those opponents returned the criticism. The question and answer period even took on a crossfire format as senators followed up one side's answer with a request for the other side to respond. It was precisely the "fight, fight" tempo that has made cable news a goldmine.

As the trial ends, perhaps justice has been done. The largely partisan vote showed that the trial could have had the sound turned off for the purposes of most viewers.

We are left with our rage undiluted by reason. It really did not matter what anyone had to say because we were only hearing half of the trial anyway.

It provided the perfect verdict on our times.

Jonathan Turley is legal analyst for the BBC and the Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University. He testified at both the Clinton and Trump impeachment hearings before the House Judiciary Committee

- Published21 January 2020

- Published5 February 2020

- Published5 February 2020

- Published5 February 2020