Why Texas is saying 'no' to all new refugees

- Published

Migrants entering Texas through the US-Mexico border

Texas wants to halt admission of all new refugees, saying the needs of Texans must be prioritised over others. But aid workers in Texas say there is sufficient help for the state's growing homeless population as well as newly arriving refugees, writes journalist James Jeffrey.

A photograph of a young Marsh Arab girl in a papyrus boat hangs on a wall of the Pita Shack diner in the northern suburbs of Austin, Texas. The one-year-old business belongs to husband and wife Ayman Attar Bashi and Raya Thanoon, who came from Iraq in 2010 as refugees after a 12-year application process.

"I would love it if there was an open door for refugees, but I understand politicians have to think about the country's safety," Thanoon says. "You see the homeless here and then see refugees getting benefits, so I understand why some people think that's not fair."

Texas Republican Governor Greg Abbott announced in January that the state would not accept any refugees in 2020. His decision came in the wake of an executive order issued from President Trump last year granting states and municipalities the right to veto the placement of refugees.

"Texas has carried more than its share in assisting the refugee resettlement process," Abbott said in a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, noting that Texas has received more refugees than any state since 2010, totalling about 10% of all refugees resettled in the US.

He also noted that Texas has faced the brunt of migration issues at the southern border due to a "broken federal immigration system".

Attar Bashi making Turkish-style coffee at Pita Shack in Austin, Texas

More than 40 other governors - both Democrat and Republican - have signalled their willingness to continue accepting refugees, leaving Texas as the only nay-saying state.

Widespread criticism of the governor's decision only intensified after he argued that Texans in need - especially the homeless -should be prioritised over refugees.

"I am putting my citizens first," Abbott said earlier this month. "We have challenges in the state of Texas that must be addressed by these very same non-profit organisations," he said, specifically referring to the state's growing homeless population.

"I would agree with the governor - that we don't want the homeless problem here to grow to the same scale - but not on the tactics," says Greg McCormack, programme director at Front Steps, which runs various homeless programmes in Austin, the Texas state capitol.

Homeless people on the streets of Austin

The Austin Resource Center for the Homeless (ARCH) is run by Front Steps and provides help and lodging

"Homelessness is the biggest challenge for Austin, but it's not a question of either or," McCormack says. "Supporting refugee resettlement programmes was in no way detracting from tackling homelessness."

McCormack says that often when politics gets involved in issues like homelessness, it ends up making things more difficult. That can lead, he says, to an overly heavy-handed response, especially when there is a city like Austin that is perceived as liberal-leaning.

"We want to both solve homelessness, and not have refugees contribute to the issue," McCormack says. "I believe both can happen."

For the time being, Abbott's decision remains moot after an injunction from a federal judge halted Trump's executive order from coming into effect.

A homeless person settles in at a centre run by First Steps

But an appeal is expected, added to which for some Texas refugee organisations the damage is already done due to growing political hostility at state and national levels toward the country's long-time commitment to take in people fleeing persecution in their home countries. The US president has said the country is "full" and threatened to send buses of immigrants to Democratic cities and towns that have decried his immigration policies.

"When the president first discussed cutting back refugees, I thought he would dial it back, I had no idea of how serious he was. Then I woke up," says Jo Kathryn Quinn, president and CEO of Caritas of Austin, a charity that in 2018 had to end its 40-year-long refugee resettlement programme.

Quinn explains how the charity's refugee programme began experiencing difficulties at the end of 2016, after Abbott declared the state would stop administering federal funding for refugee resettlement. This meant organisations like Caritas had to scramble to find alternative assistance to continue its work.

But it has been the substantial decline in refugee numbers admitted to the US during Donald Trump's presidency that proved the death knell for Caritas's resettlement programme. Its funding was linked to the number of refugees it assists. Faced with a shortfall of $3m (£2.3m), Caritas couldn't afford to continue the programme, and had to let 27 workers go.

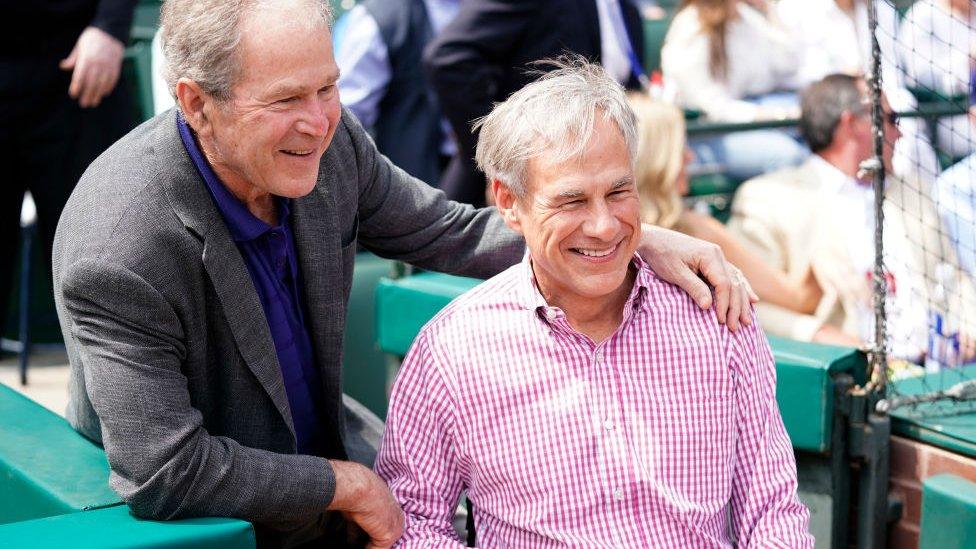

Governor Abbott (right) at a baseball game in 2019 with former president George W Bush

Every autumn, the president sets a refugee ceiling - the maximum number of refugees who may enter the country in a fiscal year. In the last year of his presidency, Democratic former President Barack Obama set the cap at 110,000.

In fiscal year 2017 - 1 Oct 2016, to 30 Sept 2017 - about 53,700 refugees resettled in the US, a drop from 85,000 the previous year, which reflects a temporary freeze on refugee admissions that Trump ordered shortly after taking office.

The following year, the president set the nation's refugee ceiling at 45,000, a new low at the time. The US ultimately admitted about 22,500 refugees. Trump then set the refugee ceiling at 30,000 for the fiscal year that ended 30 Sept 2019, a cap that was reached.

"The politicians have their reasons for the limits, and politics is about the result - you need to wait and see," Pita Shack co-owner Attar Bashi tells BBC News, adding that he includes the president in that assessment.

"I like the guy, he's a businessman who's helping the economy make money."

Pita Shack worker and Iraqi refugee Adil, 31, is in the process of enlisting in the US Army

This year's cap of 18,000 refugees would be the lowest number of refugees resettled by the US in a single year since 1980, when Congress created the nation's refugee resettlement programme.

"Capacity around the country has been lost, either through agencies shutting their doors or going out of business," says Russell Smith, director of Refugee Services of Texas, the state's largest refugee agency. "Even without the executive order, national policies and road-blocks across the country have reduced resettlement drastically."

He explains his agency has stayed afloat by diversifying to assist other displaced populations, focusing in particular on survivors of forced labour and sex trafficking.

"To the governor's credit, he's made it a priority to provide services to those who are trafficked," Smith says. "The governor's got it right when he said there are a lot of needs out there."

Crossing the border to go to school in the US

Caritas' Jo Kathryn Quinn believes that "the notion of having to pick and choose is ludicrous".

"There's plenty of resources, especially in one of the wealthiest states in the richest country in the world," she adds.

The governor's office noted that no one seeking refugee status in the US would be denied because of the Texas decision, nor would refugees be prevented from moving to Texas after initially settling in another state.

To which some counter - "Then why refuse refugees resettling in the first place, unless it is political posturing?"

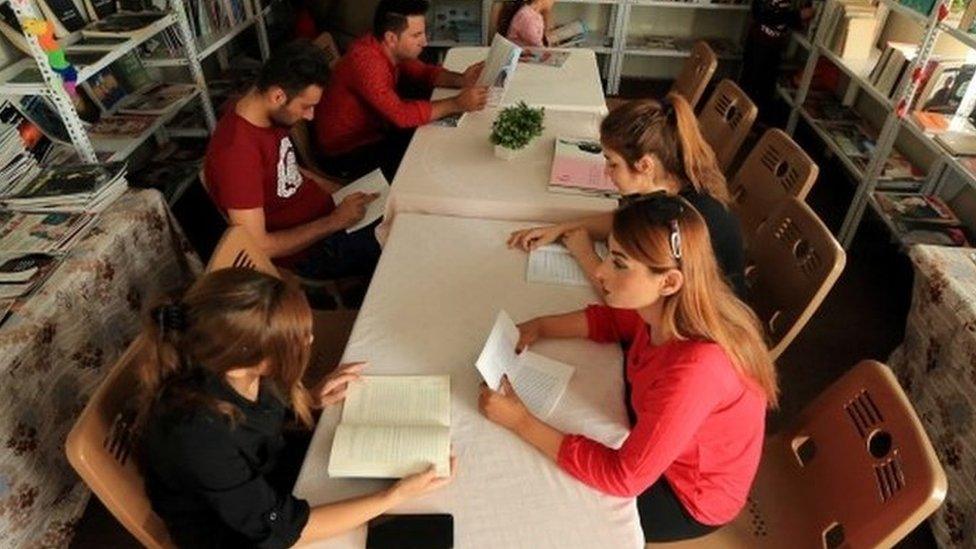

The Refugee Services of Texas holds meet-and-greets for the newly-arrived

Hence there are those who view the governor's declaration as indicative of long-term policy, and hence they view the current federal injunction as an uncertain defence.

"If he gets his way on this, I think it will become Texas policy for as long as he is governor," Quinn says.

For Quinn, an irony of the governor's position prioritising the homeless over refugees is the fact that refugees are similarly homeless. That's one of the reasons, she says, why both issues often struggle to generate as much interest and support - especially donor funding - from local populations compared to issues such as child support and animal shelters.

"People don't want to engage with homelessness, it makes them think it could happen to them, so they don't want to go there," Quinn says. "When you feel empathy, that feels uncomfortable, and most people don't want that either, so they stop themselves feeling it."

Many also see Abbott's decision as part of a larger nationwide pushback which lumps together all the different categories of displaced people - refugees, migrants and asylum seekers - as potential threats and economic drains, while ignoring the many complexities involved.

A baby shower for refugees in Houston organised by the Refugee Services of Texas

Smith notes how among the different displaced person categories, refugees endure the most thorough vetting process. It often takes years while waiting in a distant and squalid refugee camp. Meanwhile, he notes that the often-held view of refugees as a drain on the social safety net is misplaced, as illustrated by the little-known fact of how all refugees have to eventually pay back the costs of flights to the US.

"It helps them build up a credit rating for once they are living here," Smith says. "Refugees quickly become self-sufficient and civically engaged citizens, as well as tax-paying citizens - they are some of the most entrepreneurial-minded people."

"I came to Texas because Iraqi friends here told me the economy was good for work," says a 38-year-old Iraqi man who arrived in 2012 after five years interpreting for the US military in northern Iraq (he wants to remain anonymous as his family in Iraq who could be targeted for reprisals).

Since arriving in Texas, he has worked in manufacturing, security and interpretation services. "I was used to working, so I didn't want assistance, I wanted to be self-reliant."

The Africans risking death in the jungle trying to reach the US

A 2015 study by the New American Economy, a New York-based immigration research and advocacy organisation, found that refugees in Texas had combined spending powers of $4.6bn (£3.5bn) and paid a total of $1.6bn in taxes.

"This is a nation of immigrants, but refugees are part of that experience too," says Smith, who notes that his great-great grandmother had to flee Russia after helping victims of the anti-Jewish violent pogroms.

"My hope is that the governor heeds the calls that have come from across the spectrum to reverse his position before it gets to a place where it becomes a final decision."

- Published17 February 2020

- Published19 June 2019

- Published11 January 2020

- Published27 September 2019