Oklahoma City bombing: The day domestic terror shook America

- Published

On 19 April 1995, a US army veteran parked a rental truck packed full of explosives outside a federal office building in Oklahoma City and fled the scene, detonating his bomb just as the work day was starting.

The attack, motivated by anti-government extremist beliefs, killed 168 people and left hundreds more injured. At the time, it was the deadliest terror attack the US had ever seen. It remains the worst committed by an American on US soil.

This is the story of the bombing, told through five people whose lives it forever changed.

You may find some of the details in this story upsetting

It was a beautiful spring morning in America's heartland.

Kevin McCullough, an Oklahoma police officer and medical technician, was on his way to spend his day off speaking to a group of children at a local church. Robin Marsh, a local television reporter, was in a planning meeting for the day ahead.

Firefighter Chris Fields and his colleagues were going to spend their Wednesday catching up on maintenance jobs around the station. They'd just relieved another group from a 24-hour shift and were about to get themselves some breakfast.

Aren Almon didn't work in the Alfred P Murrah building herself, but lived nearby. The office block, made up of nine floors of reinforced concrete, was a hub of government offices. On any given day more than 500 workers would be inside.

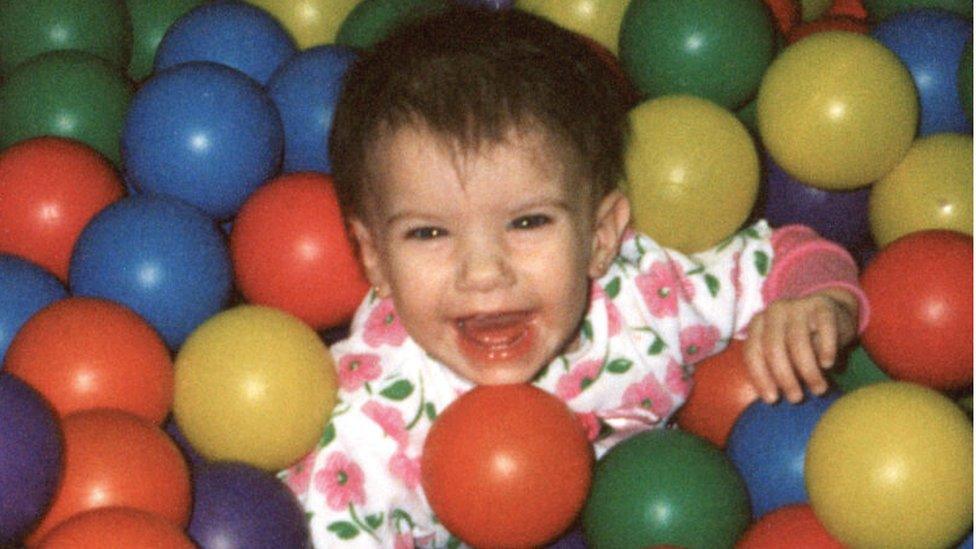

The building also had a day-care centre, America's Kids, on its second floor. On the morning of 19 April 1995 Aren dropped off her daughter there before heading to her new job six miles away. Baylee had celebrated her first birthday the day before.

Aren dropped her daughter Baylee at the Murrah building at about 07:30 that morning

For Ruth Schwab, the school run had gone smoother than normal. The mother of five got to her job at the Department for Housing and Urban Development earlier than normal that day, just before 09:00. She had just sat down at her desk and was reaching to turn on her computer when the bomb exploded.

It was the loudest noise she had heard in her life. Thousands of pounds of fertiliser and fuel had ignited, causing a massive explosion to rip through the building's nine levels.

The blast was so strong that it completely tore away the building's north side. Floors within the crater became a tangled concrete heap. Cars parked nearby were engulfed in flames, sending thick black smoke into the city's air.

The last thing Ruth remembers is feeling like she was tumbling down and down into a black hole.

For miles around, Oklahomans felt their floors tremble. The fire station's windows rattled. Kevin McCullough's ambulance shook.

It was 09:02 on a Wednesday morning and Oklahoma City would never be the same again.

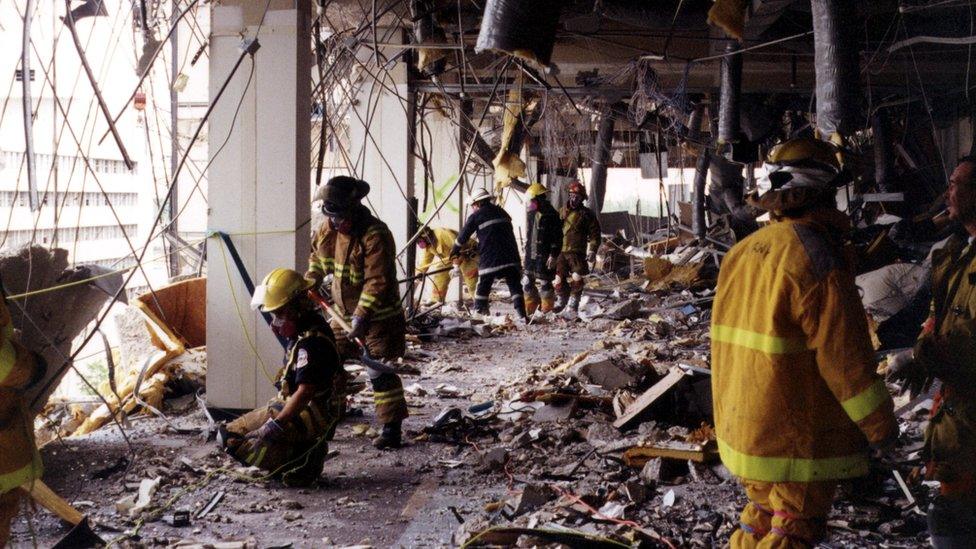

Chris Fields and the rest of Station 5 ran outside when they heard the blast. Seeing the smoke so close, they knew they'd be asked to help. They jumped in their engines and sped downtown, stopping along the way to help people injured by flying glass and debris.

"I probably didn't stand there long, but I felt like I was watching everything in slow motion," Chris says of his memories of arriving at the scene. "The debris was still falling down from the sky and seeing that building in the shape it was - even to this day - it's a daunting image."

Urgent calls went in to all first responders. Kevin McCullough turned his ambulance around and raced the few miles to the Murrah building. After parking up, he was confronted with the overwhelming and unmistakable smell of nitrates in the air. The bomb had made downtown Oklahoma City smell like a gun range.

The giant truck bomb threw dust and debris across the local area

The attack was carried out on the second anniversary of a deadly FBI raid on the Branch Davidians sect in Waco, Texas

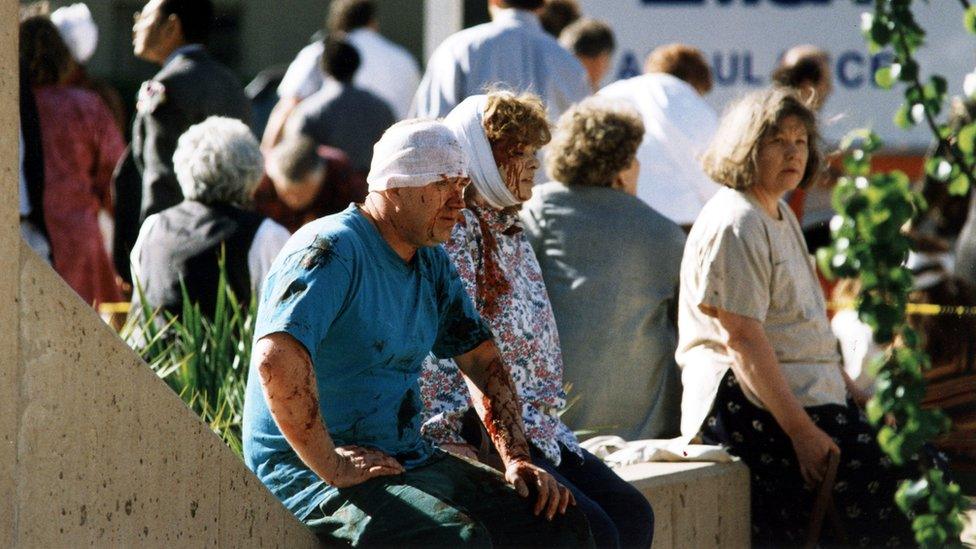

"It was a chaotic site. People were panicked," Kevin says. Some were standing dumbstruck - unable to comprehend what had just happened. Others had made their own way out of the destruction, covered in blood and dust.

When Ruth Schwab woke up, she was on her office floor. She'd been facing the direction where the bomb went off and her face had taken the brunt of her injuries. "I could smell smoke and I was hearing faint cries and moans," she remembers. "When you're blinded and can't see anything, you don't know how to help anybody."

She called out to ask if anyone was there. A friend answered back and warned her not to move. Ruth couldn't see but she was surrounded by debris and was only feet from where the eighth floor had collapsed beneath them.

Her friend helped her up, sat her down and in a kind gesture, gave her a handkerchief. "It was so sweet because that's the kind of gentleman he was," she says. "But I had to have 200 stitches in my face so the handkerchief really, really didn't do any good."

It took just minutes for local news to start covering the attack.

KWTV News 9, the CBS affiliate where Robin Marsh worked, was the first.

The network's staff had felt their building shake 10 miles away so they quickly re-routed a news helicopter that had been on the way to another story. The footage it captured, as it slowly circled the building, sent shockwaves. A giant horse-shoe shaped hole had been gouged out of the Murrah building.

The network immediately dispatched all available reporters to the scene.

The blast ripped away the building's north side, exposing the floors of offices left inside

Like others around the city, Aren had felt the blast miles away. It seemed like thunder, but the Oklahoma City sky was bright blue. Could it have been a demolition? There was always building work going on downtown.

When colleagues said it was an explosion, Aren went to find a television in the break room and saw the helicopter footage. The building where she'd left her daughter was in ruins.

Aren called her parents and a colleague drove her as close as they could get. When they reached the building, Aren and her family found a scene of chaos.

Downtown Oklahoma City looked like a war zone. Scores of buildings had been damaged by the blast.

"I remember walking to the front of the building and seeing everybody walk around with blood everywhere," Aren says. "I was surprised anybody came out of there alive."

No-one had the answers they needed. So they headed to local hospitals to try and find Baylee there.

Hundreds of people were injured in the bomb attack, with some taking years and multiple surgeries to recover

About an hour and a half after the explosion, a message came over Chris Fields's radio to evacuate. They thought they'd found another bomb.

"I think that's when everyone looked at each other like: 'What do you mean another explosive device?'" he recalls. "We didn't know it was an explosive device to begin with."

Most had assumed this was a natural gas leak or an accident. No one dared to imagine this could have been done intentionally. This wasn't New York or Washington DC - this was Oklahoma City, a Bible-belt city of only 450,000 people.

The news of the bomb scare sent people running from the scene. Among them was reporter Robin Marsh, who was broadcasting live when an official ran toward her telling her to evacuate. "You're trying to stay composed but I'm thinking, 'I need to pitch back to my anchors and get out of here. We've got to move further away'," she remembers.

As the chaos unfolded, local news stations became a vital source of information. They told people who to call and where to go for help. But in a place like Oklahoma City, the tragedy hit close to home. Some of those reporting, including Robin, knew and lost people inside that day.

By 10:30, Ruth Schwab had arrived at the hospital. She had tried walking out the building at first, but with the stairs thick with debris she was eventually passed to a rescuer and carried out. Ruth was still blinded and doctors knew they were in a race to save her eyes.

It wasn't until the second scare that Kevin McCullouch moved around the building and saw where all the injured people had been pouring from. He'd been on murder calls and traffic accidents before but had never seen devastation like this.

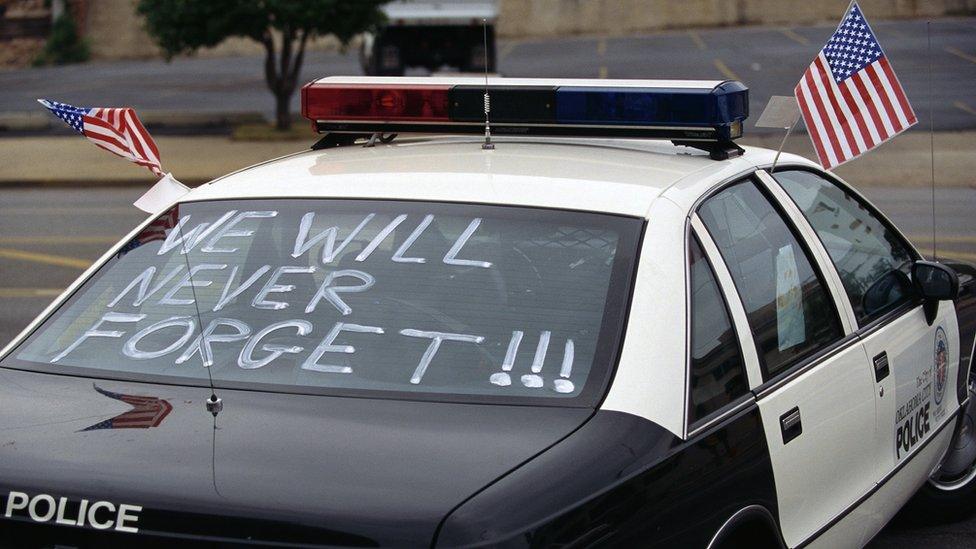

People across the local area, then the country, rushed to help at the scene

More than 250 buildings had some form of damage from the massive explosion

The main job for firefighters was search and rescue. "You try and be prepared for everything but at that point we weren't prepared for something of this magnitude," Chris Fields says. At one point, as he walked around the building, a police officer appeared in front of him with a critical infant in his arms.

Trained in first aid, Chris offered to take her. He cleared her throat, which was blocked with concrete or insulation dust debris, to try and open her airway. But with what appeared to be a skull fracture too, there was no sign of life.

Chris carried the baby's tiny frame to an ambulance. The paramedic looked at Chris: his vehicle was already full. There were already people on its floor and lying on the ground outside waiting to be transported. "And I remember him telling me: 'Let me get a blanket because we're not going to put that baby on the ground'," Chris recalls.

The firefighter held and looked down at her as he waited. Chris had a son close to her age and his thoughts immediately went to her family: "I was just looking at her thinking: 'Somebody's world is getting ready to be turned upside down today'."

He would not realise it for hours, but two photographers had captured that exact moment. The image of an Oklahoma City firefighter cradling a lifeless baby, covered in dust and blood, became the most famous of the day. The image, which we have chosen not to reprint, conveyed both the cruelty of the day and the city's loss of innocence.

But for Aren Almon, the loss was more than symbolic. Chris had been holding her daughter.

Throughout the morning, she and her parents had bounced between hospitals trying to get information. It was only when Baylee's paediatrician came around the corner with a priest that Aren's worst fears were realised. As a single mother, her life had revolved around her daughter. "I was 22, I still had my grandparents. Nobody in my family had ever died," she says.

Nineteen of those who died were children, most of whom had been in the building's daycare centre

Reports spread throughout Wednesday that the bomb could have been linked to international terrorism. But for Aren, details on who was responsible didn't matter at that point. "I was just consumed with the fact that I woke up in the morning with a child and was going to bed without one," she says.

As the day wore on, journalist Robin Marsh had ended up in a church with families still searching for loved ones. She got home at about 02:00 after a gruelling 18-hour day covering events. "I remember I just got into that shower and I just cried my eyes out," she recalls.

While Kevin McCullough continued to work at the bomb site throughout the day, trying to help victims, he had no idea that his wife had been taken to hospital in labour. His fourth and youngest child, Jordan, was born early in the afternoon.

"Typically when a new parent is spending time with their baby, you know all the joys that come with that. But I was down at the bombing site helping others deal with the loss," he says, his voice breaking. "That made it, I think, even more difficult in interaction with the people, with the parents, that has lost children down there that day."

Kevin (pictured) says his son's birth ultimately "really has helped" him cope with the pain of what happened

By Wednesday evening the death toll had climbed into the dozens, with hundreds more injured and missing. The last person to survive was a 15-year-old girl pulled from the rubble that night. In the days after, the number confirmed dead only grew.

As news of the attack spread, the images of Baylee and Chris spread around the world. "I remember going home that day, thinking that the worst thing that could ever happen has happened," Aren says. "But then I woke up the next day and looked for a newspaper."

The image of her dead daughter became inescapable. "Every time I went to the store, it was on the front of magazines," she recalls. "I would go to the doctor's office and there it was. On every television show, every news station, on the front of T-shirts, on coffee mugs. It was everywhere and it was devastating."

One of the photographers, whose version was distributed by the Associated Press news agency, received a Pulitzer prize for the shot. Aren says she continues to feel ostracised from other families, who she says felt their loved ones were forgotten amid the notoriety around Baylee. "It broke my heart that she had to be seen that way," Aren says. "I have no rights to that picture at all. I can't say how it's used… when you die your rights are abolished."

Since 2010, it has been compulsory for children in the state of Oklahoma to be taught about the bombing in school

Aren (pictured in 2001) has made sure Baylee remained a part of her other children's lives growing up

Every year Aren marks what would have been Baylee's birthday with a big family dinner.

Over the years, the firefighter who tried to save her daughter has become a close friend. "Guilt isn't always rational," Chris Fields says. "I felt a lot of guilt for Aren - she wasn't really allowed to grieve privately because of the photo. I took on a little responsibility for that."

Chris and other fire officials spent the first day searching for survivors. But after a couple of days, it was clear the operation had turned to recovery in order to help families get closure. It took years for him to process what he went through.

Eight or nine years after the bombing, everything came to a head. He had been helping someone build a pool, when it started raining. The smell of wet concrete took him back to 19 April 1995.

As evening fell on Oklahoma City that day, the bright spring morning turned to rain. "I remember someone remarking that God is crying right now about what has happened to our city," reporter Robin Marsh says.

Some emergency responders spent weeks at the site, combing the wreckage for remains

Some responders came from other states to help with the rescue and recovery effort

Over the next few months, after the pool incident, Chris felt like he was losing control.

Eventually he sought help and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He retired from the Oklahoma Fire Department in 2017, after 31 years of service, and now travels around the US speaking to first responders about mental health.

In the weeks after the bombing, the community counted its loss. On top of those who died, many had life-altering or critical injuries. A doctor had to amputate one woman's leg with a pocket knife to free her from the rubble.

Ruth was among those whose recovery took years. About a week after the bombing doctors had to remove her right eye. She had dozens of stitches in her face and her jaw had to be wired shut. "Because of my own condition, I wasn't able to go to the funerals," Ruth recalls. "I had one friend tell me it's not normal to go to four or five funerals in one day."

Her family kept the television on mute at first and tip-toed around her questions over who had been found. "My very best friend was one of the last bodies to be recovered," Ruth says.

It took more than a month for the final victims to be recovered. Some bodies were discovered only after the unstable remains of the Murrah building were demolished on 23 May.

Some 2,000 spectators were said to have gathered to see the building's implosion

Those who watched the demolition, just over a month on from the blast, including family members of victims

Those who lost loved ones then had to wait years before justice was finalised. Suspicion had initially fallen on Middle Eastern terrorists, given the World Trade Centre bombing two years before. But after finding part of a van, investigators were eventually able to trace its rental back to Timothy McVeigh.

They were then surprised to find out he had been in custody all along, having been pulled over for unrelated charges while fleeing the city. He and Terry Nichols, a former army colleague who shared his anti-government views, were indicted in August 1995 on murder and conspiracy charges. A third man worked with federal authorities for a lesser charge. But even today, conspiracy theories about a wider plot by the right-wing persist.

McVeigh was executed three months to the day before the attacks of 11 September 2001, which eclipsed the Oklahoma bombing as the deadliest terror attack on US soil.

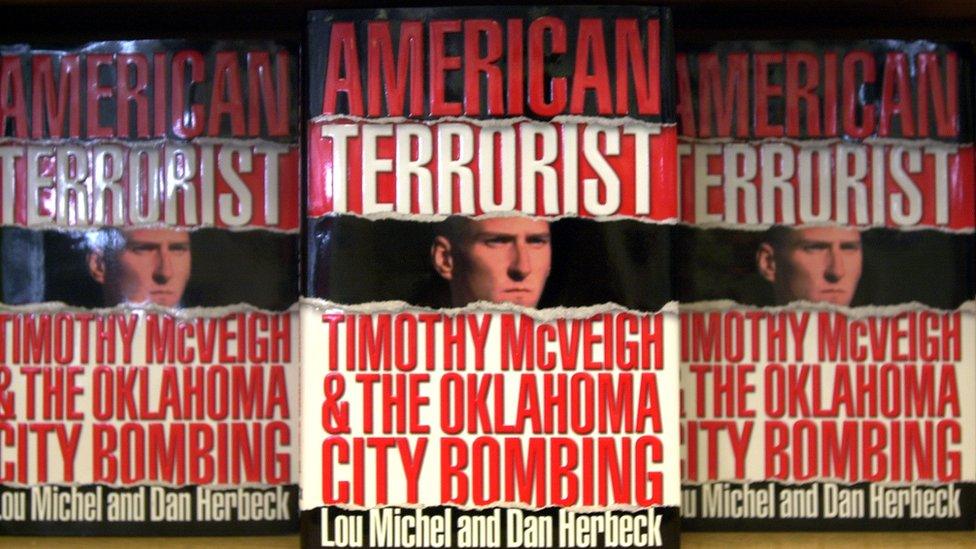

A lot of what we know about McVeigh's actions came from the government investigation, but also from a book released shortly before he was put to death. Two Buffalo News reporters, local to where McVeigh grew up, had secretly spent more than 75 hours interviewing him about his actions.

The book faced criticism from some families and supermarket giant Walmart refused to stock it

"There was a lot of backlash," Lou Michel says about its reception. "But we understood as journalists that we were doing a public service. This was history."

Dan Herbeck agrees. "I would say that if I had an opportunity to interview Adolf Hitler and get inside his mind and find out what drove him to murder millions of innocent people, I would have done that story as well.

"I think people should know as much as possible what makes these monsters tick. The only way we can prevent future acts like this is to understand as much as possible."

There is now a large memorial and museum where the Murrah building once stood.

Local children, like Ruth's grandkids, grow up learning about the bombing and visit the site on school trips. It has become a place for Oklahomans to gather and pledge to never forget.

Ruth (far left) has a big family and shares with them her experience and memories of those she lost

A memorial ceremony is held on every anniversary - this year, given the pandemic, it was streamed online

It includes a field of empty chairs for each victim and two gateways, labelled 09:01 and 09:03, to reflect the city's loss of innocence and the moment when its healing began.

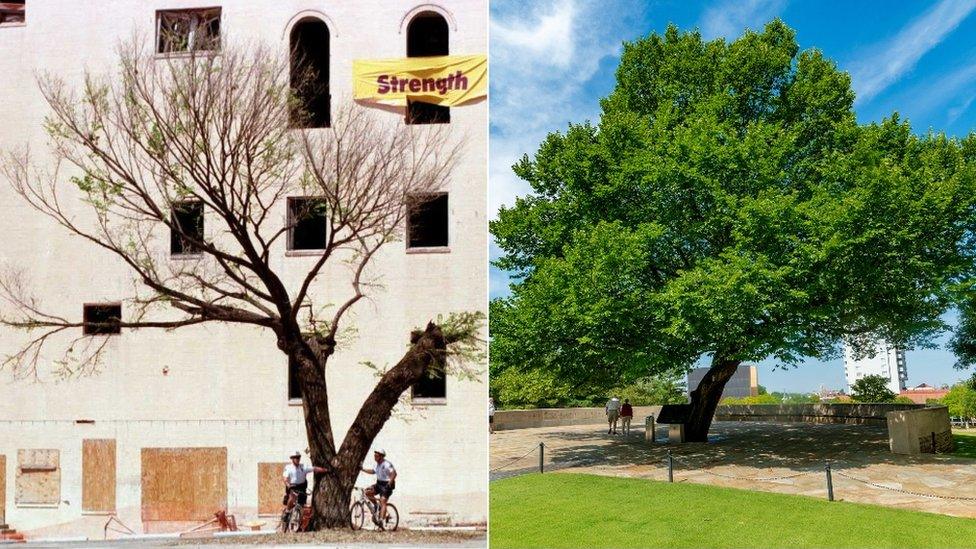

The memorial also features a giant American elm known as the Survivor Tree. Even before the bombing the tree was well-known, having stood curiously alone in the middle of a downtown concrete car park for decades.

Standing just across the street from the Murrah building, it was damaged in the blast. Investigators at one point apparently wanted to cut it down to harvest evidence.

But today, it thrives. Every year officials harvest and distribute its seeds, hoping the tree and its message can live on throughout the world. "We always say it witnessed and withstood what happened in our community," Robin, who is still a local news reporter, says.

For Oklahomans the tree has come to symbolise the city's resilience and strength: it is a reminder to keep going, even when all seems lost.

An inscription around it reads: 'The spirit of this city and this nation will not be defeated; our deeply rooted faith sustains us'

All images copyright