Coronavirus: A problem unlike anything else Trump has faced

- Published

"Every one of these doctors said: 'How do you know so much about this?'"

There are two numbers that Donald Trump has consistently cared about and watched like a hawk. And, in his mind, they are inextricably linked.

The first is his approval ratings. Nothing unusual in that. Ever since the end of World War Two and Gallup introducing its regular polling on this, every president from Harry Truman onwards has kept a wary eye on how they are being seen by the great American public - that is normal.

The second figure is the stock market. While other presidents have seen that as a barometer to keep a watch on, no-one has obsessed about Wall Street like Donald Trump. Or if they have, they haven't provided a running commentary in quite the same way that he has.

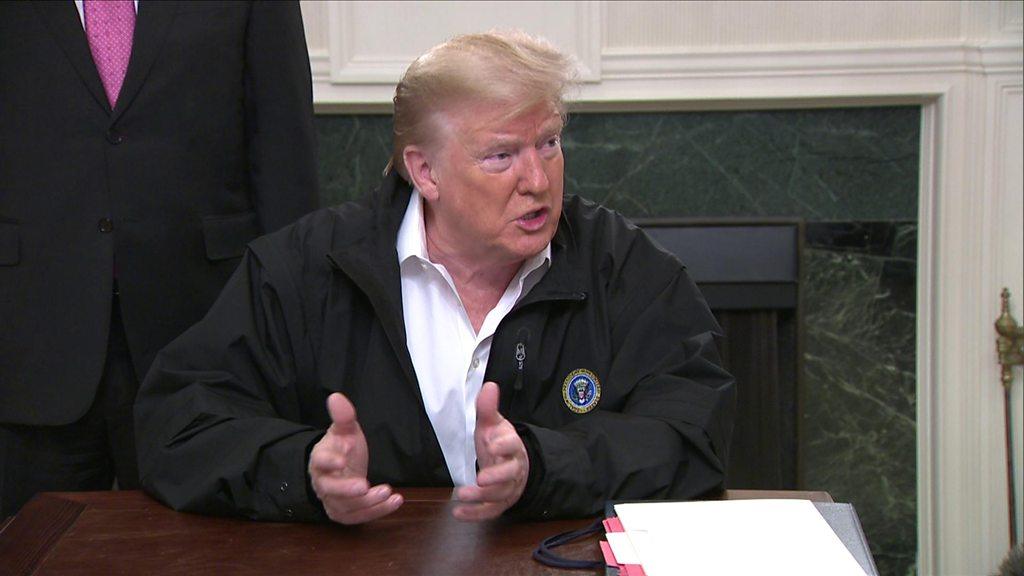

The coronavirus is continuing to spread across the US, and Trump continues to urge calm

His calculation is that if the stock market is soaring, then his approval ratings will go up and QED - he will be re-elected in November this year. So even when the stock market has the wind in its sails, the president will inhale deeply and blow forcefully in the hope of pushing the Dow Jones industrial average even higher. And every time the Dow or the S&P 500 hits a new high, he tweets to celebrate it - 280 times to be exact. In other words, roughly once every four days of his presidency he has exalted the markets.

But with the arrival of the coronavirus, the markets have taken fright - and have been plunging vertiginously over the past couple of weeks. On Monday, the steepness of the decline was such that it set off a circuit-breaker alarm on Wall Street. Markets fell by more than 7%, and so trading was suspended for 15 minutes to give traders a breath to take stock. They took a breath. They took stock. And after 15 minutes the markets continued their plunge.

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

IMMUNITY: Are women and children less affected?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

There were complicating factors that are way above my pay grade to explain - all to do with Russia and Saudi Arabia and Opec [the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries] failing to agree on cuts in production in light of the collapse in demand for oil as a result of everyone cancelling their flights because of the coronavirus. But the fright on the markets is real. And what they have heard from this administration has not been reassuring to them.

Punch and counter-punch

President Trump is used to fighting from his bunker when a crisis arrives - and let's face it, the past three and a bit years haven't lacked drama. But the coronavirus is quantitatively and qualitatively different from anything he has faced. With the Robert Mueller investigation (remember that?), there were names. People: lyin' Jim Comey, Bob Mueller, little Jeff Sessions, Michael Cohen, Andrew McCabe etc. And during the impeachment trial there was a whole host of people that Donald Trump could swing a haymaking left hook at: shifty Schiff, nervous Nancy, cryin' Chuck Schumer. As Donald Trump will tell you, he's a great counter-puncher.

But how do you hit a virus? Who's to blame? Who's the guilty party? Who do you tweet at? Covid-19 doesn't have a Twitter account.

And in the midst of a health emergency, what is sacrosanct for anxious citizens - and frankly investors on Wall Street - is reliable information, a consistency of message from the government about the risks and how they can be mitigated, and that information flow will be based on the best available scientific evidence. No other factors should intrude.

In the US, as the administration has scrambled to mount an effective response, the messages have been mixed. Not for the first time, the president has been contradicting his own advisers and medical experts. That has been a consistent feature of this presidency. Going back to the long-forgotten Mueller investigation, if the president hadn't totally contradicted his own press teams over the reasons for firing FBI director James Comey, would there have even been a need to appoint Special Counsel Robert Mueller?

From the outset of the coronavirus outbreak, Donald Trump has sought to play down its seriousness and overestimate America's preparedness. He said the spread was under control. It isn't. He's said that the number of cases may soon go down to zero. They haven't, and it was not the advice he'd been given. He suggested that people with symptoms should go to work if they felt well enough. They shouldn't.

The Grand Princess cruise ship has docked after five days stuck off shore

He has also argued that he didn't want the benighted cruise liner, the Grand Princess, because it would add to the total of coronavirus cases in the US - when it's not his fault they were on a cruise liner. "I like the numbers being where they are. I don't need to have the numbers double because of one ship that wasn't our fault," Trump told Fox News. His concern from this seems not to be preserving the safety of American citizens (the thing he swears an oath to do at his inauguration), but keeping a lid on the numbers by keeping those with the virus - literally - at sea.

Last Friday, he went to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - the epicentre of the fight against the coronavirus - wearing a Keep America Great campaign hat, and said that there were tests available for every American who needed one. There aren't. So far, only around 1,500 Americans have been tested - compared to over 20,000 in the UK with a fifth of the population. Medical experts in the US believe that the real incidence of the coronavirus is far far higher than official figures reveal. But there seemed something jarring about the president, in the midst of a medical emergency, pitching up at the CDC with a campaign hat on. Was he there as a candidate for November 2020, or the Commander-in-Chief at a time of great uncertainty?

The critique is that the reason Mr Trump is contradicting Vice-President Mike Pence (who has been put in charge of the nationwide response) and the public health professionals reporting to him, is that the president needs the markets to remain buoyant - they are vital to his re-election strategy. The kinder explanation is that he doesn't want to engender panic, leading to the ludicrous scenes that we saw from the UK at the weekend with people filling their baskets with toilet rolls (how long are people planning to self-quarantine for?)

Mixed-message impact?

Take Mr Trump's tweet on Monday morning as Wall Street was in freefall. "So last year 37,000 Americans died from the common Flu. It averages between 27,000 and 70,000 per year. Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of coronavirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that!"

But while common influenza is most certainly a killer, experts estimate that the coronavirus is markedly deadlier. So at the same time as the president is tweeting this, officials are on the airwaves saying the crisis is real, that Americans need to respond, and it is going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

For all that Donald Trump may want Americans to carry on as though nothing has happened, behaviour is being affected. Airports are quieter, planes are emptier, hotels are easy to get cheap bookings at. If you're in the hand sanitiser business or you're Netflix (I have allowed myself the momentary fantasy of trying to calculate how many box sets I could get through if I self-quarantine), things have rarely looked rosier. For much of the rest of the economy, it's looking pretty grim.

It is perfectly possible that the mixed messages will do the president no harm. How many times have commentators stroked their chins (something health advice tells us we should avoid) and come to the conclusion that this time the president will be deeply damaged, only for whatever perceived transgression to pass without so much as a dent to the bodywork? Frequently, is the answer.

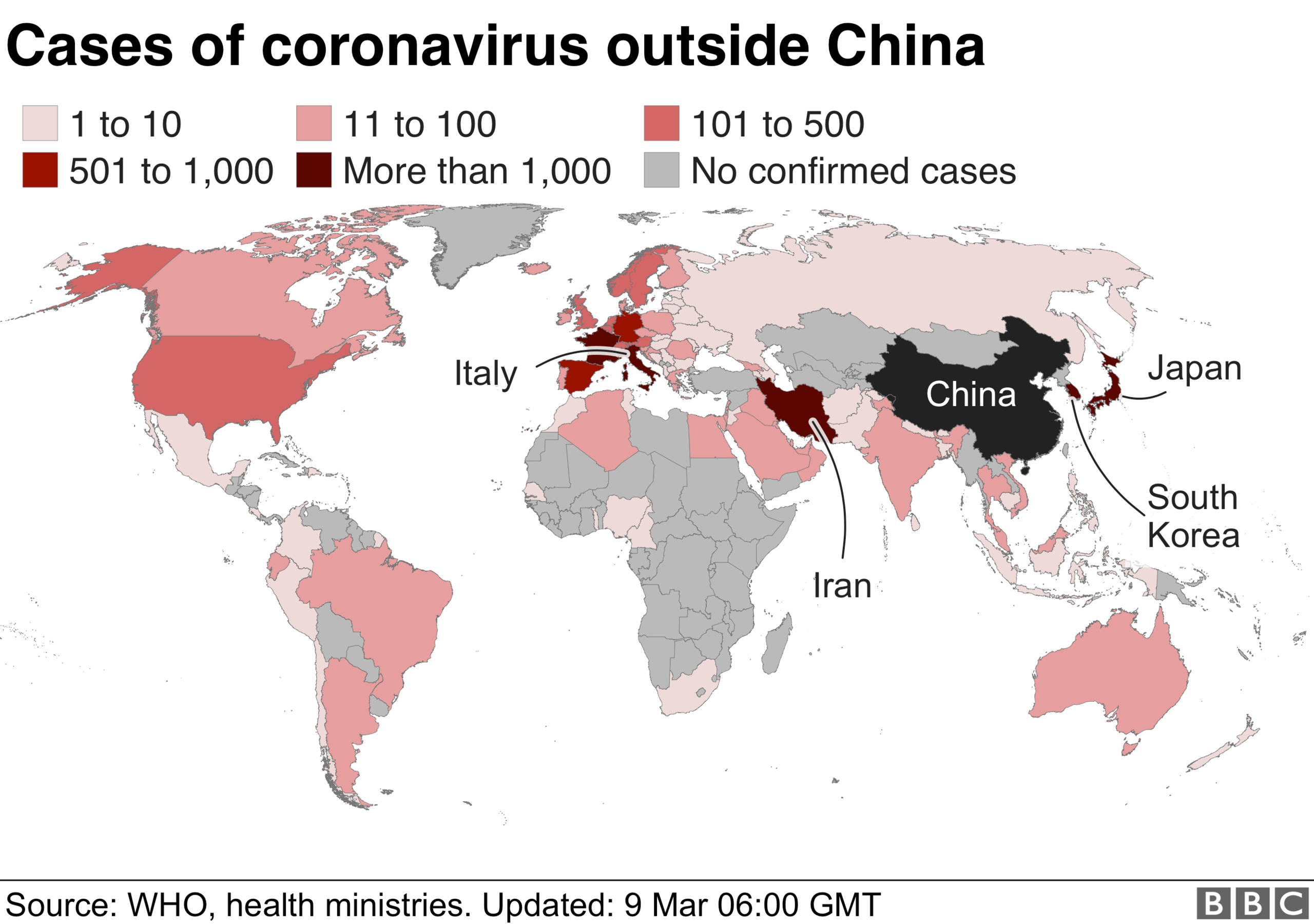

The president hasn't before had to deal with anything like this - a health crisis whose trajectory is uncertain - though if northern Italy and South Korea are anything to go by, it could get very serious indeed in the US.

But there is something else that needs to be addressed about America and its preparedness for dealing with something like this - and this has nothing (well, more or less nothing) to do with Donald Trump and his administration. Yes, his gutting of the entire global-health-security unit of the National Security Council might now seem rash. Ditto, eliminating the US government's $30m (£23m) Complex Crises Fund.

US is different and worried

A lot of this goes to the foundation of what the US is and is not.

America does not really have a welfare state. The safety net it offers its citizens is threadbare, to say the least. Yes, there are a range of highly innovative social policy programmes that were left over from the New Deal in the 1930s or the War on Poverty in the 1960s. Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act has resulted in many more millions having health insurance - but it is a long way short of what Europeans understand as a welfare state.

Just consider testing. A friend of mine who lives in DC had been travelling abroad. He comes back to the US and develops first a really sore throat, then a cough, and quickly afterwards a temperature. He is concerned. He rings his GP, who tells him they have no testing kits. He rings the local hospital - they tell him they haven't got the capacity to deal with it. This is not weeks ago. This is last weekend (he seems much better now, I should add).

But let's say the health system is perfectly geared to meet his concerns - and the clinic or hospital says sure, come in, let's get you tested. But now imagine my friend doesn't have great health insurance (or any insurance for that matter). Although the administration has decreed that the test is an essential health benefit, a lot of individuals will still be left with huge bills. Just like when you insure a car in the UK, you will have an excess - so you will have to pay, say, the first $500 of any claim - so in the US there are "deductibles". With your health insurance, there will be a sizable deductible that will fall to the citizen to pay.

Steps the NHS says you should take to protect yourself from Covid-19

There is also the co-pay. That is the element of the cost of a prescription you will have to pay. I have often stood behind people at my local pharmacy who've not taken the drugs they were prescribed by the doctor because the co-pay is so high. The Financial Times estimates the cost of the coronavirus testing to be borne by individuals could cost thousands. If you're barely subsisting and living "pay cheque to pay cheque", where do you find the money for that?

Or what if you are simply feeling unwell, or you may have been exposed to someone who has contracted the virus? The current advice is that you should self-quarantine for two weeks. Two weeks? That is two weeks without pay. Two weeks where you are sitting at home and you may develop nothing. It might be two weeks that will need to be repeated at a later date.

Currently, there is no federal sick pay in the US. Eleven states, as well as Washington DC, offer sick pay. That means there are 39 states which don't. It means that the US has fewer work days lost to illness than virtually anywhere else on the planet.

But what if you want the employee to stay at home? The impetus if you are sick is that you will continue to go to work, increasing massively the risks that the coronavirus spreads like wildfire. Anthony Fauci, the head of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases - and the doctor who has been a clear voice at all the White House briefings on the coronavirus - said at the weekend that he was concerned by the growing incidence of "community spread" - in other words, where the source of the virus is unknown.

I heard from a friend at the weekend who is a health professional in the UK National Health Service (NHS). She told me that they had repeatedly "war-gamed" disaster scenarios - not exactly the same, but the sort of emergency that would put enormous strain on the system: of what they would do, of how they would make beds available. She described a command-and-control structure that would cascade down from central government to regional health bodies, and which in turn would pass on advice to the hospitals, GPs' surgeries and clinics that will deal with patients.

And just as on major policing events, like mass demonstrations or riots, there would be a gold command and silver command. She thought there would be serious strains, and on a "reasonable worst case planning scenario" - the phrase being used to deal with the gloomiest end of projections - the system might be overloaded.

No buttons to press

But at least there is a system - not perfect by any means. Those working in the gig economy in Europe will also not want to self-quarantine and lose their money. The NHS is bureaucratic and cumbersome, but there are levers the UK prime minister can press in London that will result in things happening around the country.

The US president has a button which, if he presses, can lead to nuclear Armageddon, and another one on the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office that will lead to one of the White House stewards bringing him another Diet Coke.

But perhaps on health and social welfare provision in a time of emergency, this is one occasion when the man in the French presidential palace at the Elysée, and the bloke in Downing Street and German Chancellor Angela Merkel in Berlin and poor Signor Conte, the Italian prime minister, in Rome - and that's not forgetting all those tax-heavy social democracies in Scandinavia - have more power to make a difference than the guy in the White House.

US capitalism is fantastic when markets are booming and the state lets you get on and lead your life without interference. Maybe not so good when the chips are down.

- Published6 March 2020