How the Cornish pasty came to prosper in Virginia

- Published

You don't expect to find a British pasty in a small corner of Virginia. So how did the Cornish delicacy wind up thousands of miles away across the ocean, asks Jonathan Turley.

The famous Greek physician Hippocrates once said "let food be thy medicine." In a pandemic, that means comfort foods that transcend feelings of isolation and desolation.

For Anglophiles living near Washington, DC, there is an island of normalcy amidst the uncertainty of life under lockdown. A refuge where one can indulge in such quintessentially English delights as Cadbury's eggs, McVities digestive biscuits and, of course, the eponymous pasty.

Most Americans are unfamiliar with that Cornish delight. Indeed, you have to be careful to pronounce your love for "PAST-eez" rather than "PAY-stees" or your neighbours will think that you frequent strip joints.

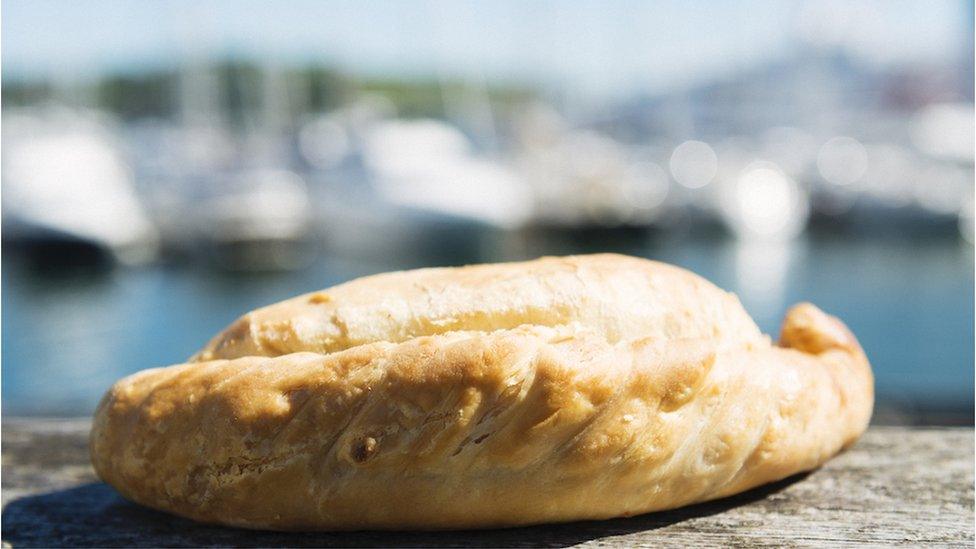

But the flaky handheld meat pie is a staple of British cuisine, earning mentions in Shakespeare. The version we eat today was popularised in the 19th Century in Cornwall, in the southwest of England, amongst labourers who appreciated the portability of this filling lunchtime treat.

So how did the Pure Pasty shop make its way to Vienna, Virginia?

Founder Mike Burgess, 58, says he suffered something like a midlife crisis when he quit his job in IT in his 40s. But while most middle-aged men buy a sports car or take up surfing, Burgess took every dime he had and decided to open a pasty shop across the sea.

Born in Nantwich, Chester, Burgess had heard from his mates that they could not find a pasty in the States to save their soul. Seeing a demand without a supply, he set out to learn how to make the perfect pasty with the same focus as someone venturing on a spiritual journey.

Rather than going to an ashram, Burgess went to Cornwall to learn the essence of the pasty. He continued to work on his technique, even using a local pub in Kent as a laboratory for his culinary creations.

The Cornish pasty was given protected status by the European Commission in 2011

He moved to the United States in 2009 and a year later opened his own shop, with the help of another ex-pat, Nicola Willis-Jones. From Yorkshire, Willis-Jones had once cooked for the Queen as a member of the Air Force but had relocated to the US and was longing for English cuisine.

Shortly before he opened, she rang him and offered her services. She was hired on the spot and he credits her for helping him developing the recipes and for perfecting the crust.

Since then, ex-pats and displaced Brits have flocked to the little shop in Vienna to get their fix of pasties and other English groceries, from British back bacon to Balson's bangers to Branston's pickles.

But Burgess would not truly earn the title of "perfect pasty" until he returned to Cornwall to compete in the World Pasty Championship - the Olympics of pasties. In 2018, he shocked the pasty world by winning the top prize - the first for an American pasty shop.

How the pasty conquered the world

The Oxford English Dictionary suggests that the pasty was identified in Cornwall in around 1300

But it was much later with the advent of tin mining that it took hold in the county, says Les Merton of The Official Encyclopaedia of the Cornish Pasty

Miners could easily carry it underground, and the crust could be held onto with dirty hands and then thrown away, along with any arsenic poisoning that may have rubbed off on it

The emigration of miners in the 19th and 20th Centuries meant the savoury snack went global

His win, in the open savoury category for his barbeque chicken pasty, caused an uproar over his unconventional use of the ingredient pineapple.

Many denounced the notion as wholly non-traditional, if not heretical. Making matters worse, a local shop had jokingly entered a pastry in the shape of a pineapple. In the ensuring hoopla over the "Hawaiian Pasty," people assumed that the pineapple pastry was his winning pasty. He received tongue-in-check messages of possible riots and even a threat by one pasty aficionado to secede from Cornwall.

Pineapples aside, Burgess won again in 2019 again in the open savoury category. In 2020, it grabbed the silver medal with a near perfect score of 97 out of 100 points.

These days, Burgess worries about his family and friends back in England. He wants his fellow Brits to hold firm and to know that they will come through this together on both sides of the ocean.

In the meantime, he is committed to keeping the pasties flowing as his way to remaining unbowed to this virus.

With the chronic shortage of toilet paper and sanitisers due to panic buying, Burgess will not allow hoarding of pasties. He limits purchases to just eight per customer for curbside pickup.

Locked in a home with one's children for a couple months, a supply of pasties is essential. Indeed, it should be listed under the Defense Production Act for pandemic necessities.

After all, pasties have long been featured in history's most trying times. When Falstaff seeks to comfort weary travellers in The Merry Wives of Windsor, what does he offer with the ale "to drink down all unkindness"? Venison pasties, of course.

In our own unkind times, pasties serve the same Falstaffian function for all wanting a taste of normalcy.

Covid-19 has forced Burgess to close his shop to the public, and put a limit on the number of sales

As an American who fell in love with pasties and digestives when visiting England, The Pure Pasty converted my family faster than Beckham could bend it.

Returning with our precious load, the kids eagerly grabbed their favourite pasties from Leslie's Moroccan Lamb to Madie's Chicken Masala to Aidan's Chicken Cordon Bleu to Jack's Traditional Beef. We sat in reverential silence; each alone with his or her pasty panacea.

After all, there are some things that simply transcend words.

As Parolles stated in Shakespeare's All's Well That Ends Well, "if ye pinch me like a pasty, I can say no more".

Jonathan Turley is a legal analyst for the BBC and the Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University