Appalachian Trail: Covid postpones the great American adventure

- Published

As America grows restless after months of Covid lockdown, there is a yearning for the beauty of the great outdoors - and there is no communion with nature like hiking the Appalachian Trail.

Nestled between trees of a thick wood and the cascading waterfalls on the side of a Georgia mountain, there is an iconic stone archway that marks the entrance to an adventure.

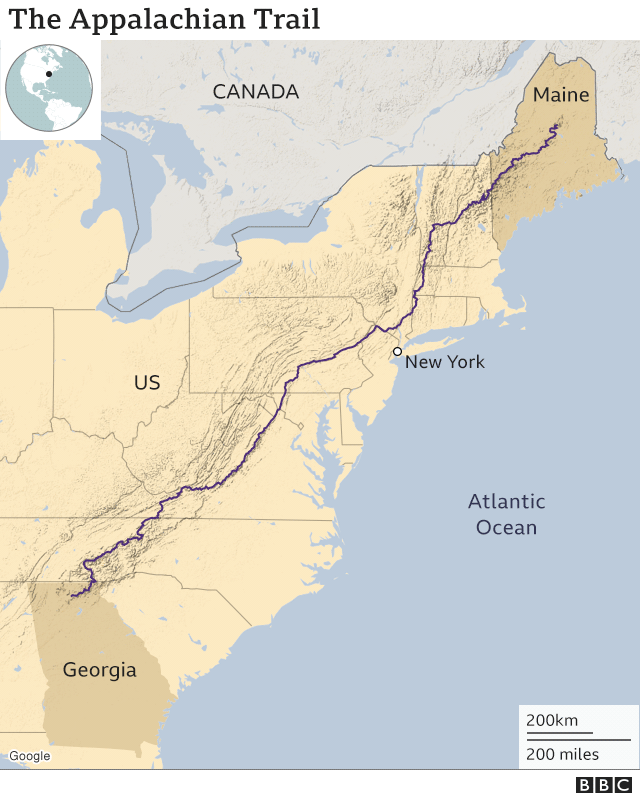

The southern head of the Appalachian Trail, the world's longest continuous footpath, begins there, on Springer Mountain, and cuts its way nearly 2,200 miles (3,540 km) across 14 eastern US states, ending at another summit - the rocky, bare top of Mount Katahdin in Maine.

When travelling along the way, there is loneliness, hardship, fear and sometimes even death to face - yet each year, some 3,000 people attempt to hike the full length of the trail, beginning the trek in spring.

Two-thirds of would-be trail conquerors, the "thru-hikers", take this north-bound route, making it to New England before the late autumnal northern chill ends the hiking season.

But like so much else that has been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, this season the best-laid plans (which can take as much as three years to prepare) to tackle this stretch of American wilderness have been scuppered by the disease.

With the country under lockdown, there are those dreaming of the day when they can come back to the great outdoors, says Larry Luxenberg of the Appalachian Trail Museum, which was forced to postpone plans to induct members to its 2020 Hall of Fame this month. The great trek lies waiting, a symbol for the exploration to come.

Treks through woods, mountain, fields and towns are part of the trail's appeal

It may well be that there is no time to wish to shrug off cares more than after a calamity. The idea for the Appalachian Trail originated in 1921 after a tragedy.

Benton MacKaye, an American conservationist, conceived of a "sanctuary and a refuge from the scramble of everyday worldly commercial life" that would run through the Eastern US as he was grieving the death of his wife.

The first person to complete the journey, Earl Shaffer, did it in 1948, after serving in World War Two. He wanted to "walk the army out of [his] system", he said.

In the decades since, the trail has been expanded, maintained and kept up by affiliations of local outing clubs that look after bits of the trail, loosely overseen by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) charity. Volunteers help hikers along the way, look after shelters and clean up the paths that cut through wood, mountain, field and road.

Today, hiking the trail has become "the quintessential American adventure", says Mr Luxenberg. Bill Bryson, the travel writer, rediscovered his lost America and wrote a book; Mark Sanford, a former Republican governor, only pretended to - though he claimed to have gone on the hike in 2009, he was on an adventure of a rather different sort.

People are drawn to the "A.T." for much the same reason as before - because they want a challenge, an adventure, to have a break from modern life, especially in times, as now, of trial.

"You see this during the pandemic. There's this real hankering to reconnect with nature," says Mr Luxenberg.

However, hundreds have been forced to abandon their journeys of a lifetime since 31 March, when the ATC urged all hikers to go home.

The Doyle Hotel, a favourite stop for hikers, was forced to close this season due to coronavirus

Lodges and food stops along the route are shuttered, volunteers have cut back and locals in "trail towns" along the route, on whom hikers must rely for inevitable help, have gone indoors. The ATC has said it will not recognise hikers who undertake trips during the outbreak.

Coronavirus has "pretty much just killed our northbound season", Vickey Kelley, whose hotel, the Doyle, in Duncannon, Pennsylvania, is a famed spot for hikers, told The Inquirer newspaper. She was forced to close as the hotel was due to celebrate its 115th year.

In Franklin, North Carolina - another "trail town" - dozens of hikers were left stranded in April when orders came to go home and the local hiking festival was cancelled.

Warren Doyle, a trail educator (who is not affiliated with the Doyle hotel), was to have been one of the four honorees inducted to the Appalachian Trail Hall of Fame this month.

He has walked the full length of the trail 18 times since 1973 - the record for the most "thru-hikes" along the "A.T."

Ironically, even when there wasn't a global pandemic, "I've never encouraged anyone to do the trail- people might find that surprising," Mr Doyle says, "[but it's] because I don't want to be responsible for their pain and suffering,"

However, he will advise anyone who asks him, he says, because the journey is the closest thing in modern day America to the great explorations of the past - like Lewis and Clark, perhaps.

The first time he set off in 1973, he had been in the midst of completing a programme at the Highlander Folk School, an alternative education institution in Tennessee that taught social justice and trained leaders of the American civil rights movement, including Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr.

"My first hike was a pilgrimage," he says, "I was going to go do something that no-one was telling me to do, had no extrinsic reward- no trophies, no cheerleaders. It was going to have to be done alone, and it was going to have to be difficult. It was to see not how much I could take, but how much I could give up. It was quite the journey."

The Lotus Eaters and Lord Tennyson were on his mind when he went, thinking of ancient wandering philosophies, from the Homeric journey to the Aborigine walkabout.

There were many days when he cried from sheer loneliness, he says. It was the only time he undertook the trip alone - for the next 17, with others, including he leading groups on ten of the expeditions.

He reckons he has led over a hundred people to complete the trek. Those who sign up to go on the expeditions with him must pledge to finish. They begin the trip forming a circle atop Springer Mountain to mark its start, and months later, all re-form it again when they reach its end.

People tell him when they finish that the most poignant feeling is that of experiencing "more than they could have ever expected - more discomfort, more beauty, more adventure, more challenge... just more."

He added: "I would say to the hundreds of people who gave up their A.T. dreams this spring: 'the freedom and simplicity of the trail itself will never be closed'."

- Published26 May 2016

- Published3 May 2020