US recession: What can the 2008 recession teach us about this one?

- Published

Layoffs, stock market crashes and bailouts - America has been through this before. Can we learn from the Great Recession of 2008, or are we doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past?

Then: Wall Street blew up the economy

The Great Recession was not caused by a deus ex machina or a stroke of bad luck - it was caused by some fundamentally poor choices made by Wall Street.

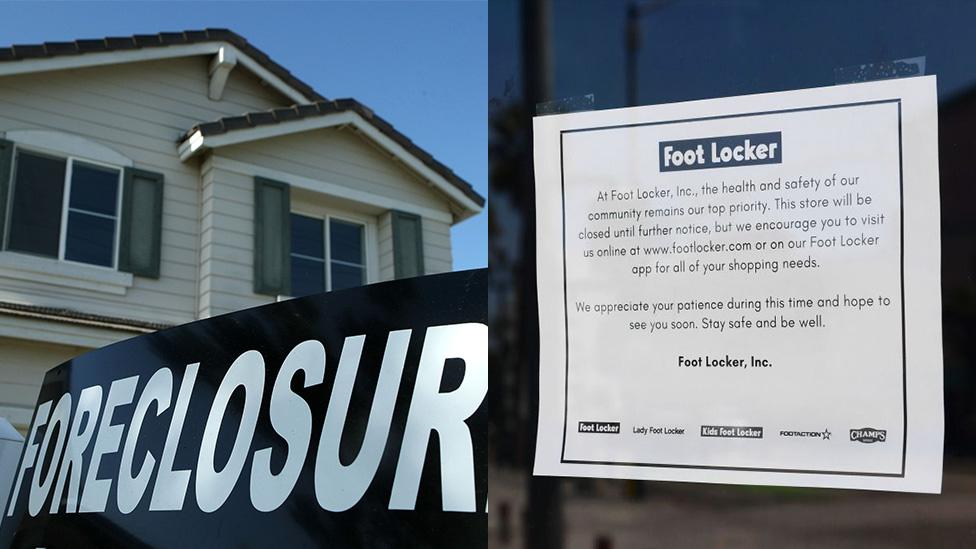

During the housing boom, bankers had given mortgages to people with credit and income challenges.

Many banks then sold these mortgages off as investments called mortgage securities to other banks, who bundled the debt with other similar loans. The idea was that these bundles would make the bank more money when the loans were paid off, but when foreclosures rose, many banks began to fail.

In order to fix the problem, the government passed reforms - like the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010 - and created the Troubled Asset Relief Program (Tarp), a $700bn programme to let the government bail out failing banks.

At the time, bailing out big banks and failing industries like the auto sector was highly controversial - many felt it was rewarding companies for making bad decisions.

But ultimately, increased oversight, coupled with financial support from the government, has been credited with keeping the financial system from completely collapsing.

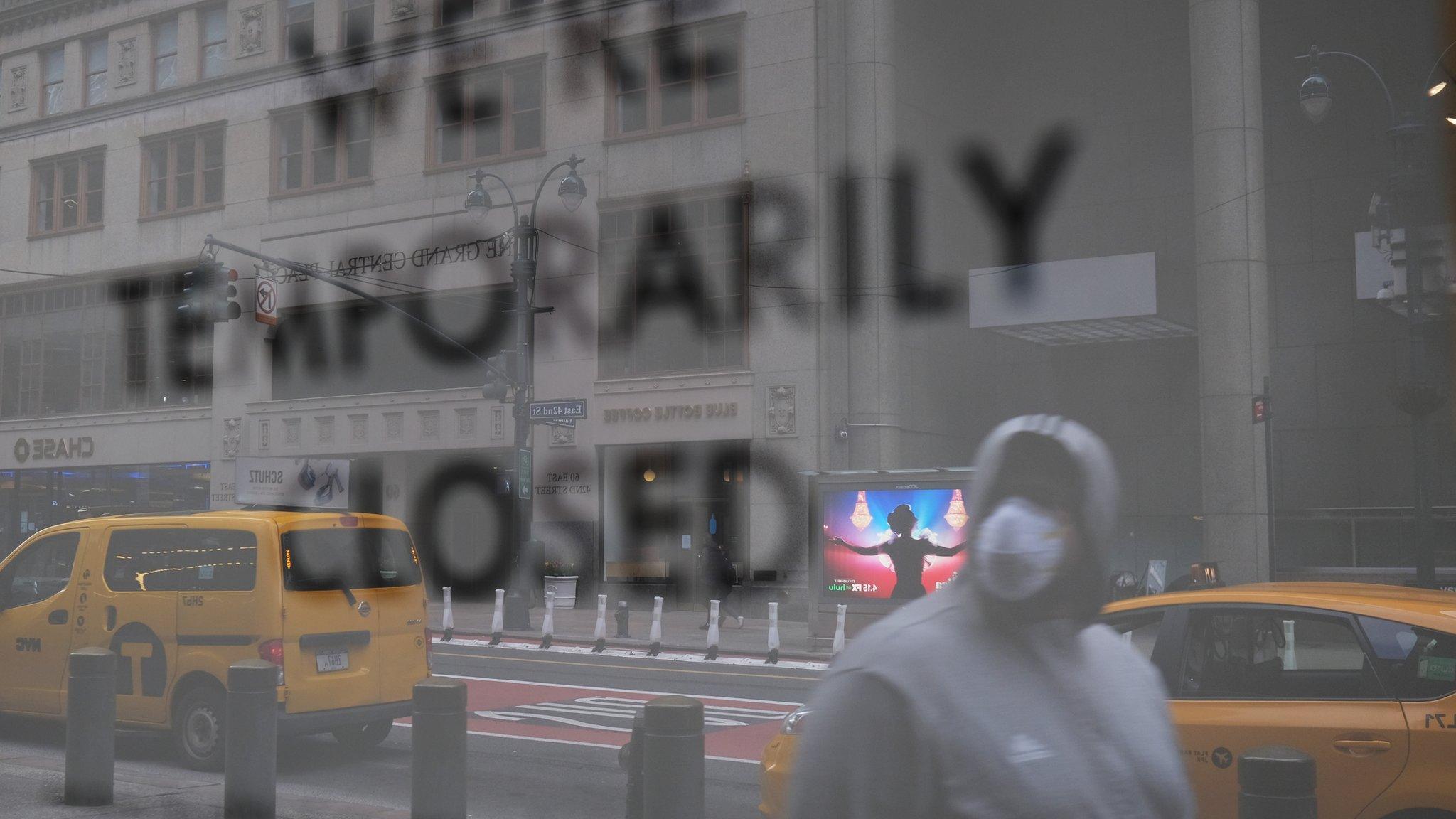

Now: Main Street has collapsed

The current recession is not caused by a broken link within the system, but from an external threat, a worldwide pandemic. In order to keep the disease from spreading, many governments forced non-essential businesses to close and brought in lockdown orders, bringing many industries to a grinding halt.

But luckily, the overall financial system is in much better shape this time around - in part because of some of the policy changes made in response to the 2008 the recession.

Markets have already partially recovered, and the Dodd-Frank act has helped make banks much healthier and able to withstand the market downturn, says Todd Knoop, an economist who researches the history of recessions at Cornell College.

"Policy makers have developed a script - while details of that script has changed over time, they have a much better idea of what to do during a crisis than they did during the Great Depression, or even in 2008," he says.

But helping businesses has proven trickier, says Duke University economist Campbell Harvey.

"I don't even call it a bailout. A bailout to me means you're bailing out somebody that's done a bad job. Whereas this is more like aid," he says.

The scale and the complexity of delivering this aid has proved a challenge as well. In the US, about 40% of the population is employed by over 30m small businesses.

"In the Great Recession, the policy makers could summon the CEOs of the top 25 financial institutions into a room and literally hand out their bailout cheques," he says.

"Whereas this recession, it's not really the financial institutions that are being hit, but (millions of) small and medium-sized businesses."

Then: The system broke down

Prior to 2008, the prevailing attitude amongst economists and regulators was that markets would take care of themselves. It seemed to be working - just months before the economy began to shrink, the stock market had reached an all-time high.

But the palace was built on quicksand. When foreclosures began to rise, banks that had heavily invested in mortgage-backed securities, which are investments tied to other people's home mortgages, began to fail. People lost their retirement savings, and companies completely unrelated to either banking or real estate lost investments they needed to keep their businesses afloat.

It took many by surprise.

"I think the reason why most economists didn't understand how bad this was, is most economists couldn't wrap their mind around how stupid some of the players were being," Mr Knoop says.

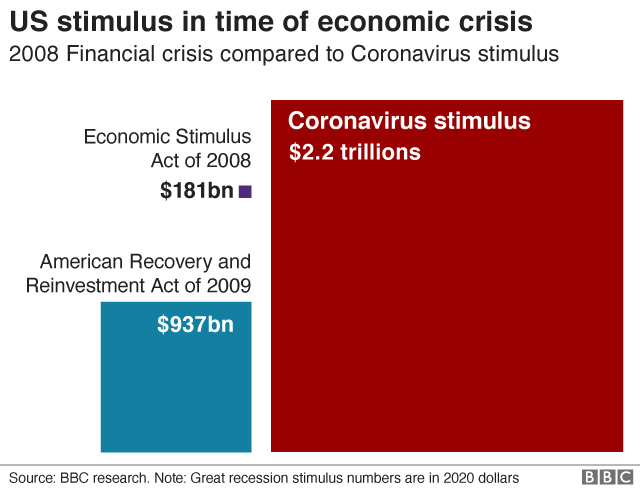

To fix the problem, the US officials unveiled a number of programmes and policies aimed at getting the country back on its feet, including passing two separate stimulus packages worth approximately $1 trillion (£800bn) between 2008-2009.

The Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero and launched a quantitative easing programme, which is when the Fed buys investments to increase cash flow.

Now: The system has transformed

It's still early days, but politicians seem to have learned some of the lessons of 2008.

"Now we expect the government to take a very active role," Mr Knoop says.

It took over six months from the collapse of the 85-year-old investment bank Bear Sterns - one of the earlier bank busts in the recession - for the Fed to drop the interest rate to zero in 2008.

This time around, the Fed slashed interest rates to zero within days of President Trump declaring coronavirus a national emergency and spent $700bn on a new quantitative easing programme.

Just two weeks later, Congress passed a $2.2 trillion stimulus package to help the millions of Americans out of work, and a second stimulus may be on its way.

But how we go about our day-to-day lives, from taking public transport to working from an office, has completely transformed and the "new normal" could be here to stay for a while. Some companies like Canadian tech giant Shopify may get rid of offices altogether, while others may look into automating certain jobs.

"This is really destroying people and it's destroying human systems, in the way we share ideas and technology and interacting with each other," Mr Knoop says.

Then: It was like a slow-moving panic

One of the defining aspects of the Great Recession was its length.

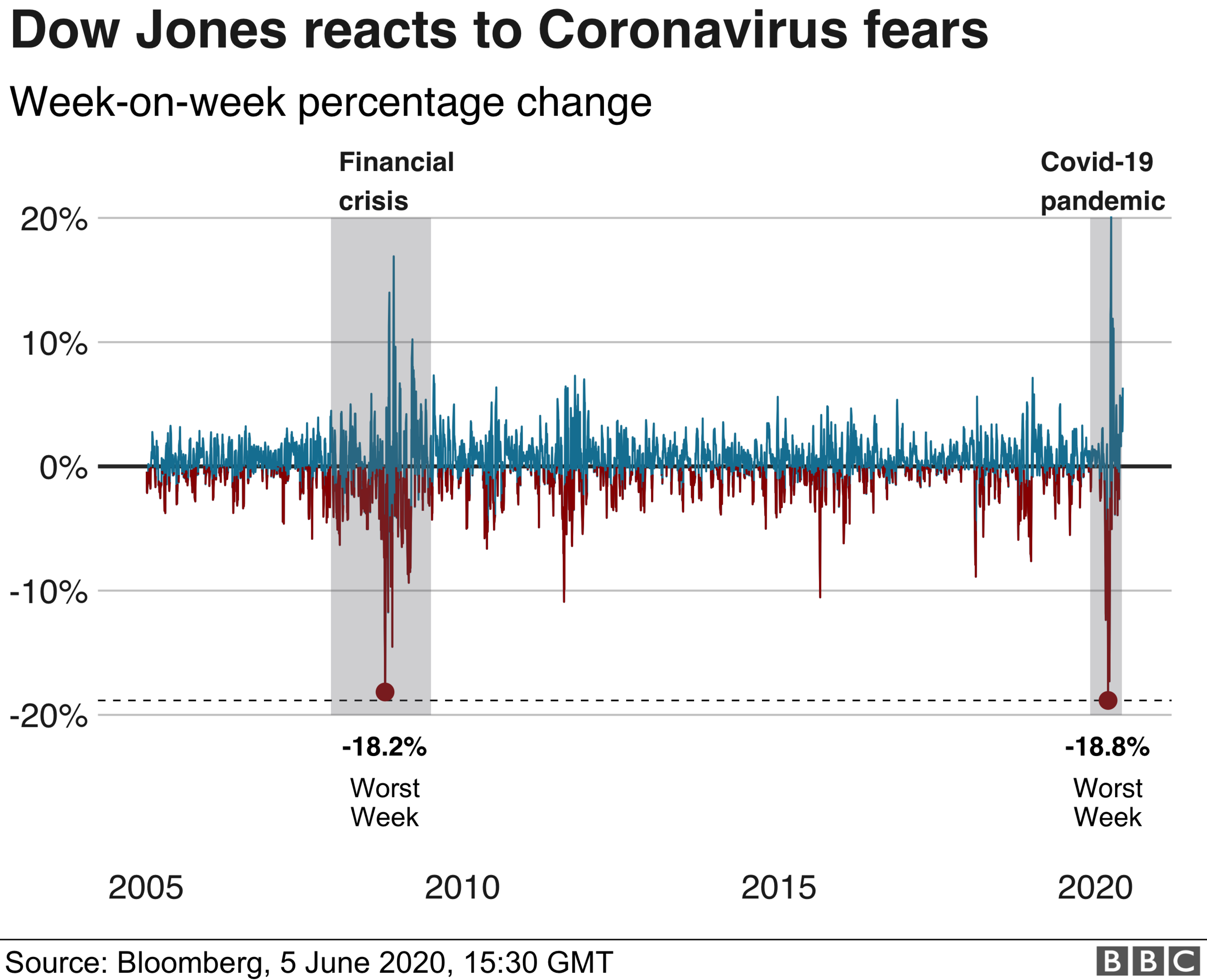

The National Bureau of Economic Research retroactively noted that the economy first began shrinking in December 2007. Bear Sterns investment bank collapsed in February 2008, but it wasn't until September that the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 777.68 - its largest point crash in history, until 2020.

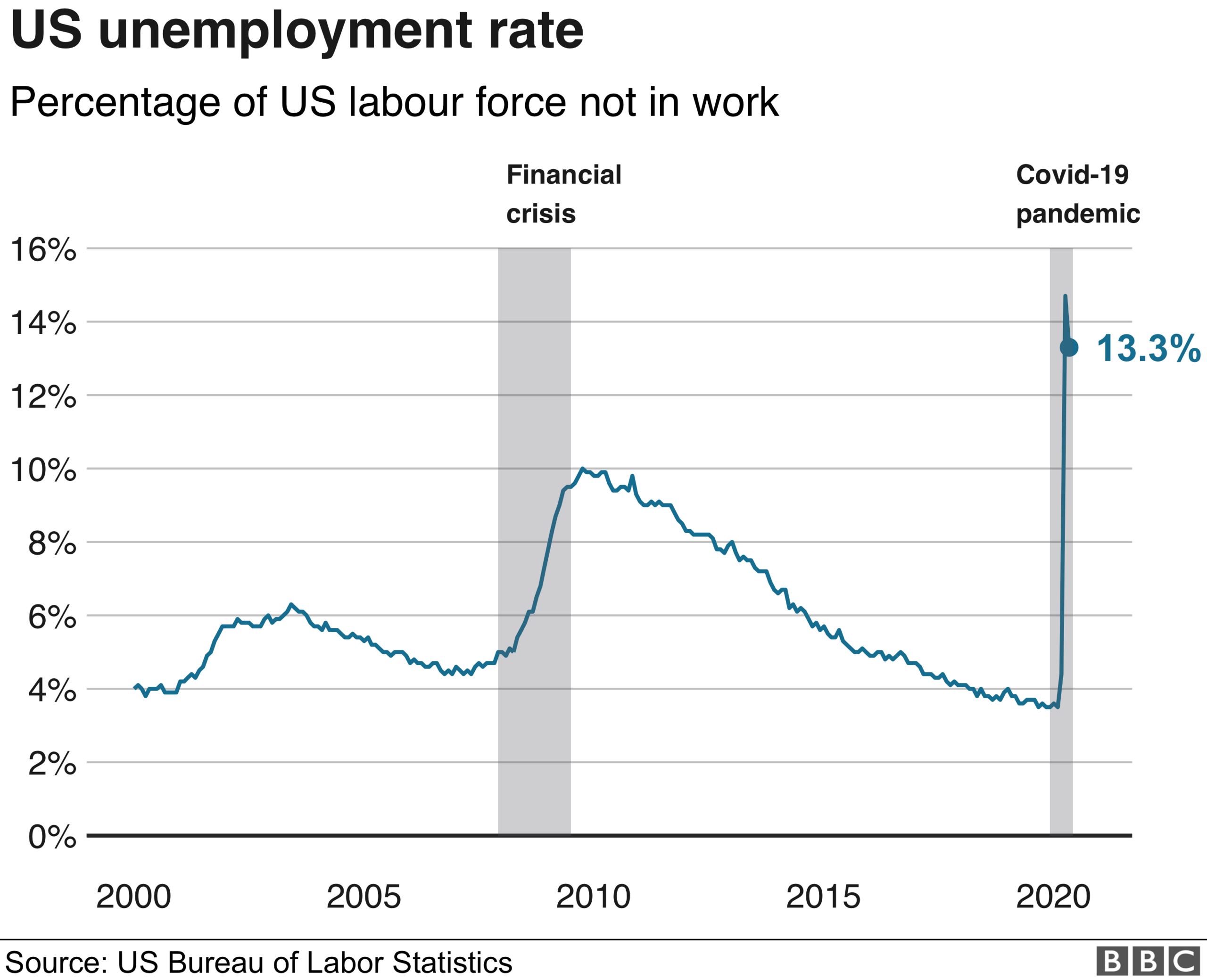

Meanwhile, jobs began to slowly disappear. By October 2010, the unemployment rate had peaked at 10%.

Recessions are fuelled by uncertainty - uncertainty that the financial system can really recover, uncertainty that one's job is safe.

"If there's a lot of uncertainty, companies don't make capital investments and consumers don't spend," Mr Harvey says.

During the Great Recession, this uncertainty dragged on. Even after the stock market recovered, and production increased, employment lagged, and it wasn't until 2017 that it returned to its pre-recession lows.

Now: It's like a hurricane

If the Great Recession was a long-term degenerative illness, then the coronavirus economic downturn is like a natural disaster that takes out everything at once, says Mr Harvey.

"You just can't pull out the playbook of 2008 and apply it to 2020," he says.

"With a pandemic, there's no place to really hide - everyone is affected around the world."

Between March and April, the unemployment rate jumped 10 points to over 14%. GDP - the value of goods and services made in the US - dropped by nearly 5%.

But there is a silver lining, Mr Harvey says.

The uncertainty of this recession is mostly biological - in the beginning, we didn't know how deadly the disease was, what its side effects were, or what kinds of treatments might be effective. But as time goes on, science advances.

As soon as a vaccine is developed, companies will be able to reopen without fear, which means they can rehire people, Mr Harvey says. Whereas in 2008, it wasn't clear when it was going to end.

There are signs the economy is already starting to recover - data from May released on Friday shows that the unemployment rate has gone down to 13%, a slight decline from April's high of 14.7%.

Everyone won't make it, Mr Harvey says - some will close their doors permanently.

"The key thing for policy makers is to minimise the collateral damage," he says.

That means ensuring that stimulus packages are hearty enough to keep good businesses on life support until they can reopen their doors.

But some are sceptical everything will start right back up again.

"When the economy starts up, when social distancing comes to an end, when we have a vaccine, will employment go right back up to where it was the day before the pandemic hit?" asks Mr Knoop.

"Who knows, maybe, but I think it's kind of unlikely."

- Published24 January 2021

- Published9 April 2020

- Published2 June 2020

- Published8 June 2020