George Floyd death: Why has a US city gone up in flames?

- Published

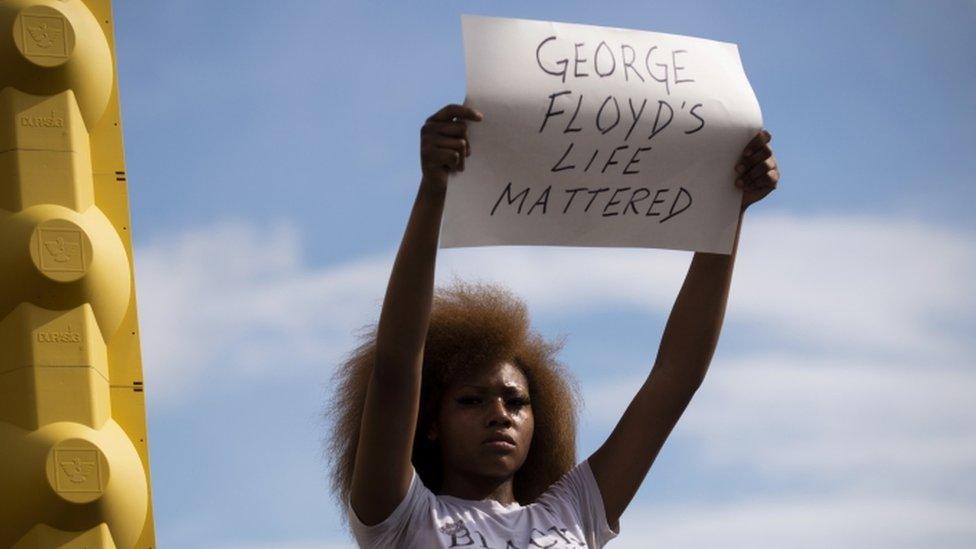

Tensions between Minneapolis' black community and the police did not start with the death of George Floyd. They have been years in the making.

On a hot Thursday morning in the Longfellow neighbourhood of Minneapolis, a 28-year-old father named Nuwman stood outside the Minneapolis Police Department's Third Precinct drinking a large coffee as smoke wafted past from the smouldering ruins of nearby buildings.

It was day three of protests over the death of 46-year-old George Floyd, after a white police officer named Derek Chauvin kneeled on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds. Floyd begged for his life before falling unconscious and dying in the street, in full view of witnesses and a rolling mobile phone camera. Four officers, including Chauvin, were fired from the department for their involvement.

The previous night, tensions ignited, and for the first time the city saw looting, arson and violence. At least one man died in a shooting at a pawn shop.

"This is everyday. Everyday that these police officers have enforced their protocol has led up to this," said Nuwman, his voice rising with emotion over the din of protesters and sirens. "This is not just a singular moment. This is a cataclysm. A combination of all the things that happened before."

That night, protesters stormed the precinct as police cruisers flew out of the rear parking lot, abandoning it to demonstrators who quickly moved from room to room lighting blazes.

The following afternoon, a Friday, saw the arrest of Chauvin by Minnesota's Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. Chauvin has been charged with murder.

This is not the first instance of a controversial, police-involved killing in the region. In 2016, Philando Castile was shot and killed by a police officer in a neighbourhood just 15 minutes away from the current epicentre of protest.

In 2017, a Minneapolis officer was charged with the shooting death of Justine Damond after she called to report a possible sexual assault. In 2015, protests erupted over the shooting death of Jamar Clark, a 24-year-old man who was being pursued by Minneapolis officers.

All three deaths sparked protest movements and yielded mixed results in terms of prosecution. Yanez was tried and acquitted. Mohamed Noor, Damond's shooter, was sentenced to 12.5 years. No charges were brought in Clark's case.

Racism in the US: Is there a single step that can bring equality?

For some, Floyd's death was the continuation of those stories.

"WE SHOULD HAVE BURNT THE CITY DOWN FOR PHILANDO CASTILE," one person posted on social media.

But in some ways, the pictures beamed around the world this week tell a story that's unique.

Demonstrations are occurring in the midst of a historic, global pandemic. The sheer amount of property damage and arson has been staggering. The swiftness with which officers were fired, and the speed in which Chauvin was arrested and charged surprised many.

But Minneapolis - while a prosperous city that celebrates liberal policies and politicians - has struggled for years with socioeconomic inequality and segregation. It's a phenomenon that's been dubbed the "Minnesota paradox".

The Twin Cities, as Minneapolis and St Paul are known, are still overwhelmingly white - about one-quarter of the population is non-white - and its neighbourhoods are still highly segregated. Most people of colour live on the cities' north sides.

They were shaped by racist red-lining policies dating to the early 20th Century, when black families were not allowed to buy homes in certain neighbourhoods. In the 1960s, the state built a major highway that cut through and destroyed a thriving black community known as Rondo in St Paul.

'Why we want Americans to talk more openly about race'

According to a 2018 study, external, the rate of black homeownership in the Twin Cities is among the lowest in the nation.

Even before the pandemic caused massive layoffs, 10% of black residents were unemployed compared to 4% of whites. That disparity ranks as one of the nation's worst.

In 2016, the average white household in the Twin Cities made about $76,000 a year, while the average black household earned just $32,000. Thirty-two percent of black Twin Citians fell below the poverty line, while only 6.5% of whites did.

Racial disparities persist in the way the community is policed.

After Philando Castile was killed, data released about police traffic stops in the area showed that 44% of stops were black drivers, though the population was only 7% black.

Protests spread to other cities including New York City

According to the Minneapolis police department's own data, in 2018 55% of drivers stopped for "equipment violations" were black.

As Covid-19 ravages the area, these disparities are sure to worsen, as thousands lose their jobs, and their homes to evictions and foreclosures.

On Friday afternoon, residents of both St Paul and Minneapolis headed into the streets carrying brooms and pails, and slowly began to literally pick up the pieces of the town.

Following the announcement that former officer Chauvin had been jailed and charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter, protesters at Minneapolis City Hall let up a cheer.

But it was quickly replaced by a new demand: "One down, three to go."

- Published29 May 2020

- Published29 May 2020

- Published28 May 2020