Does Trump have the right to send in federal forces?

- Published

The National Guard is an army reserve force

US President Donald Trump has said he would deploy the National Guard - part of the US armed forces - to quell violence that has broken out in some US cities.

Mr Trump has repeatedly attacked Democrat governors and mayors for their response to clashes in cities they run.

Following the death of George Floyd in May, President Trump threatened to send the US military into states which saw protests and sometimes violence.

But the mayors of some cities and state governors have questioned the president's right to do so against their wishes.

Who can deploy the National Guard?

Each US state has its own contingent of National Guard forces, which can be deployed by the state, or sometimes be asked to work for the federal government.

President Trump has said: "My administration coordinated with the state and local authorities to very, very swiftly deploy the National Guard surge federal law enforcement to Kenosha and stop the violence."

When protests broke out in Kenosha, Wisconsin after the shooting of Jacob Blake, it was the state governor who requested help from the National Guard the next day.

The governor also asked other states to help with additional forces, including Arizona, Michigan and Alabama, external.

But if the local authorities don't deploy the National Guard, is there any legal basis for the president to do so?

There is a law called the Insurrection Act, dating back to the 19th Century, which allows the president to deploy federal troops against the will of local authorities in certain circumstances.

What is the Insurrection Act?

The US law lays out circumstances when the government in Washington DC can intervene without state authorisation.

The Insurrection Act says the approval of state governors isn't required when the president determines the situation in a state makes it impossible to enforce US laws, or when citizens' rights are threatened.

The law was passed in 1807 to allow the president to call out a militia to protect against "hostile incursions of the Indians" - and it was subsequently extended to allow for the use of the US military in domestic disturbances and to protect civil rights.

"The key point", says Robert Chesney, a University of Texas law professor, "is that it is the president's determination to make; the governors do not have to request his help."

Has the law been used before?

According to the Congressional Research Service, external, the Insurrection Act has been used dozens of times in the past, although not for almost three decades.

It was last invoked in 1992 by then US President George Bush Sr during riots in Los Angeles, after the governor of California requested federal help.

The law was used throughout the 1950s and 60s during the civil rights era by three different presidents, including when there were objections from state governors.

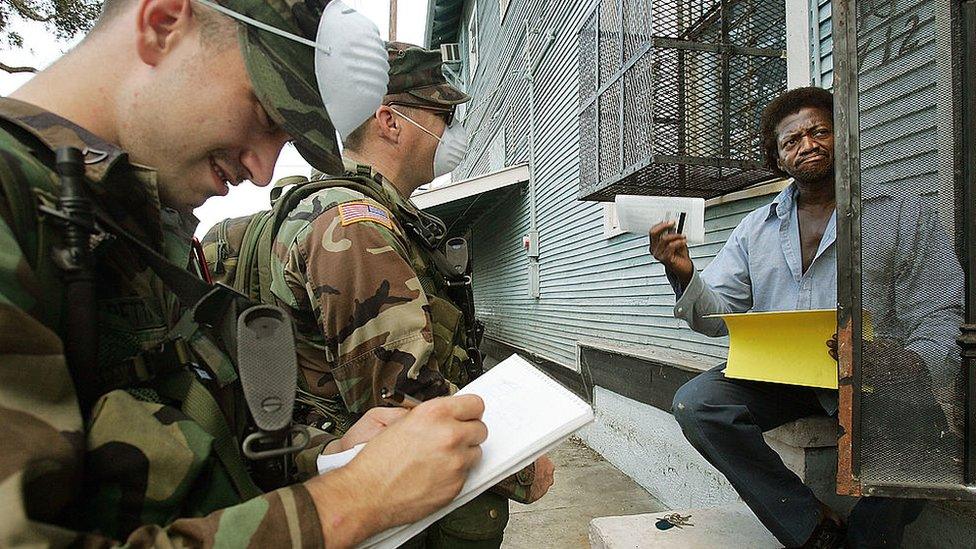

The National Guard were deployed to Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina

President Dwight Eisenhower faced objections when he used the law in 1957 to send US troops to Arkansas to control a protest at a school, where black and white children were being taught together.

Since the end of the 1960s, the use of the law has been rare. Congress amended it in 2006 following Hurricane Katrina in an attempt to make military assistance more effective, but the amendment was repealed after state governors objected to it.

Can President Trump send in federal agents?

Mr Trump has also ordered hundreds of law enforcement agents into cities, which he says are seeing rising rates of violent crime.

Police powers in the US are left in the hands of state and local officials rather than the federal government as set out in the 10th amendment of the US constitution, external.

It is not unusual for the federal government to send agents into cities to help with specific law enforcement and investigations.

But the potential scope of the latest operations without requests from local authorities has raised eyebrows.

The head of the US Department of Homeland Security has said: "I don't need invitations by the state, state mayors, or state governors to do our job. We're going to do that, whether they like us there or not."

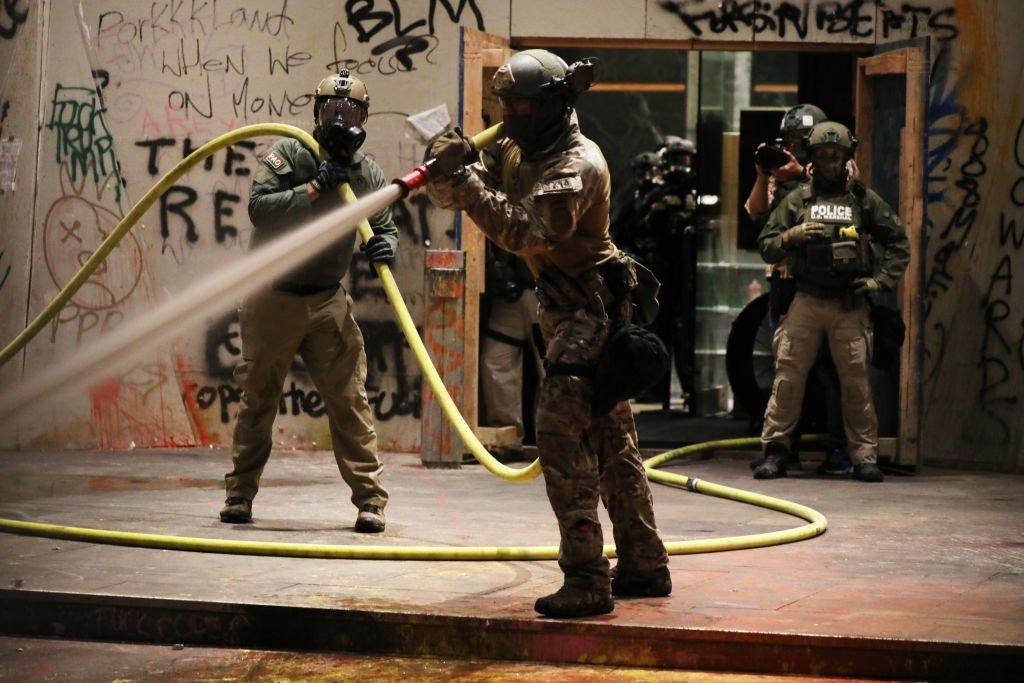

Federal forces in Portland, Oregon say they are protecting a federal courthouse.

The federal government has a right to protect federal property - and a 2002 law details that federal officers can be deployed for "the protection of property owned or occupied by the federal government"., external

This was the rationale given for sending federal agents into the city of Portland recently to stop alleged vandalism.

But the Trump administration has launched a separate operation focused on policing violent crime, rather than protecting federal property.

The US government has the right to enforce federal laws, investigate crimes and make arrests.

In the US constitution, an arrest is legal if supported by "probable cause" - that there's evidence to show that the person arrested has committed an offence.

But some experts have suggested the agents could be stretching the legal limits of federal law enforcement, as general policing is within the jurisdiction of local authorities.

Elie Honig, a US legal analyst, says: "The federal government certainly can target hard-hit areas to investigate crime, but what is problematic here is the potential of deploying federal agents to patrol the streets."

However, as Mr Honig notes, it's not clear if the agents will conduct patrols, and even if they did it would not be illegal as they don't require permission from local law enforcement.