George Floyd killing: Why I decided not to watch the video

- Published

Since the video depicting a white Minneapolis police officer kneeling on George Floyd's neck went viral, it has been near impossible to escape it.

But I, a black woman, made the decision that this time I wasn't going to watch the video.

It is mentally and physically draining for me to watch yet another unarmed black man dying under arrest at the hands of another white police officer.

I know there will be plenty of people telling me I should be glad the video went viral because it unveiled the truth - a deep social and systemic problem that has been ongoing for centuries in the US. As a journalist, what could be more important to me than getting to the truth?

But over the years I have found there is a fine line between exposing these horrific acts and safeguarding my mental health, especially when the story is so deeply rooted in my own experience.

George Floyd was heard crying out 'I can't breathe' before he died

I think anyone watching these videos will find them distressing, but it resonates on a completely different level for a black person like me; these images can act as traumatic triggers.

'Just too much'

When I spoke to Nia Dumas, a 20-year-old African-American woman living in the US, she told me she could not stop crying after watching George Floyd's last moments.

"I have found myself crying sometimes four times a day since watching it," she said. "It has been very traumatic."

Nia lives in Cleveland, Ohio, where she has seen a lot of violence. Growing up, images of black people being killed were almost constant in her life.

"If it's not George Floyd, then it's someone else. It's just too much," she said.

"For me, seeing his video triggered memories of when Trayvon Martin was killed. I was around 11 years old then and it's crazy how I've been seeing stuff like this for years. I'm tired of it."

University student Nia lives in the US state of Ohio

Trayvon Martin was an unarmed black 17-year-old, shot dead by a Florida neighbourhood watchman, who was cleared of any wrongdoing in 2012 on the grounds of self-defence.

It was Trayvon's killing that brought about the first use of the Black Lives Matter hashtag.

'I just felt broken'

Since then, that hashtag has been used many times over, as Toni Adepegba, a 27-year-old black British man, told me when we spoke about racism and its impact on mental health.

"It's been a heavy month," he said, "only weeks since the video of Ahmaud Arbery's video surfaced. I had barely recovered from seeing the images of Ahmaud's killing and then I saw it happening again."

Ahmaud Arbery, 25, was jogging when he was shot dead during a confrontation with a father and son in the US state of Georgia.

For Toni, watching George Floyd's final moments was almost too much to take in.

"I don't have the words to describe that feeling. I just felt broken. I just felt tired because these men could have been me."

Earlier the same day, he had watched another viral video of a white New York woman in Central Park, who was calling the police for help after a black man, a bird watcher, asked her to put her dog on a leash, in line with the park's rules.

UK-based camera operator Toni Adepegba: 'These men could have been me'

"This was triggering for me," Toni said, "because it exposed the dynamics at play; she was aware of the privilege that she had as a white woman over a black man.

"She knew that she could get this man arrested or even killed with one phone call."

Toni could not watch the full video of George Floyd.

"My first thought when I saw it was, 'Why are people just standing there?' But maybe they understood that they could easily be where he was."

More on George Floyd's death

The USA's history of racial inequality has paved the way for modern day police brutality

VIEWPOINT: Tipping point for racially-divided nation

TIMELINE: Recent black deaths at hands of police

CRIME AND JUSTICE: How are African-Americans treated?

HOW IT HAPPENED: The last moments of his life

In recent weeks, I have had numerous conversations about whether there is any benefit in sharing these images on social media.

Paris-born Laëtitia Kandolo is a 28-year-old black woman whose family comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

She struggled to watch the George Floyd video at first.

'This is our reality'

"There were so many emotions to process. But a couple of hours later when it was just blowing up, I went back to watching. He was completely helpless, and I identified with that helplessness."

Laëtitia Kandolo, a creative director, works between France and the DRC

"We have to find a way to hold racists to account," says Laëtitia. "If these videos, make those who are privileged because of their skin colour to stop and think, then so be it."

But she added, "It's important to remember that [white people] are watching the video, whereas we are living it - this is our reality."

For many black people, seeing this video shared by non-black people brings up the question of authenticity.

'What do you contribute to the conversation?'

Nia, from the US, is sceptical about the support she sees online, if deeper issues such as white privilege and institutional racism are not addressed.

"I have seen a lot of predominantly white celebrities sharing ready-made posts, which I think is kind of artificial," she said.

She has seen people who genuinely want to be supportive, which she appreciates. But she is not going to "applaud a fish for swimming".

"I want to know how you feel, what you think as an individual, or what you contribute to the conversation, We've normalised the thinking that sharing a post, video or retweeting is showing support... We are beyond that now."

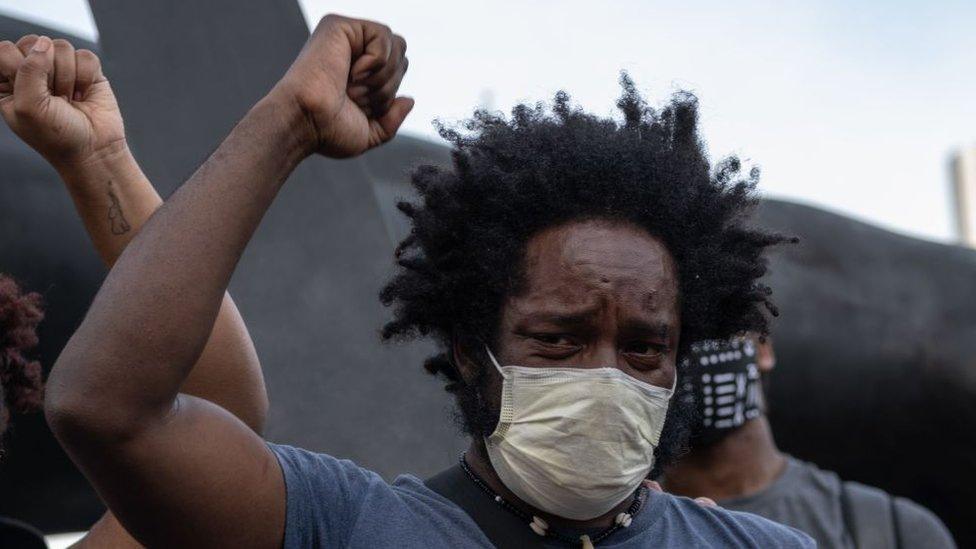

George Floyd's death prompted huge protests in the US

'It still plays on my mind'

When black people come across such videos, they inevitably see themselves, or their families and their ancestors, behind a hashtag.

"I was doing a lot of running at night when Ahmaud's video came out," Toni said.

"It dawned on me the high likelihood that someone could see me running and just call the police with the assumption that I'm running away from a crime scene. It still plays on my mind that if I was in America, I could have been him."

"Every black person has a moment", Laëtitia said, "when they realise they are black and what that means to the world at large."

For her, it was a conversation she had with her father when she was 18 and wanted to go to fashion school.

"He told me, 'You're black and as a black person in an artistic sphere you will struggle, you will have to worker harder than everyone one else to be seen.' I felt crushed. I cried."

'His story is also my story'

Black people from around the world know too well that the experience of racism ranges from the extremes to the daily micro-aggressions, all rooted in the same history.

In my case, growing up as an African in multicultural east London, I felt somewhat cushioned from blatant racism at first, but once I left for university to study journalism, I also had to deal with the "real world".

My afro became a topic of conversation. It went from "sassy hair" to "a mane" to being told that I had "moppish hair" - which could hinder my career.

The trauma that racist videos and images trigger in black people is linked to many such memories, either personal ones, or collectively shared.

A protest organiser cries during a demonstration over George Floyds's death

"I think we are realising more than ever that George Floyd's story is also my story. We are connected and are part of a broader story," said Laëtitia.

"These images have historical significance and weight for black people; from the images of lynching to the mutilation of hands in Belgian Congo, these pictures are traumatic. They've been trying to kill us, but we're still here fighting to live."

But these images can become exhausting for a black person, to the point that it may be damaging their mental health.

I've felt the overwhelming pressure to continuously read, share, post and actively engage with everything on my social media feed about the latest hashtag on a racist killing, until George Floyd's video came up, when I made a conscious effort to protect myself.

'Your mental health is your priority'

Toni said he also had to find a balance between engaging with the conversations about racism and protecting his mental health.

"There is a need to ensure that George Floyd is not forgotten." he said.

"But I've been saying this to other black people, that they shouldn't feel pressured to see these images or share them. Your mental health is your priority.

"It's not a black versus white thing, it's a humanity thing. I believe change can only happen when it stops being 'their' problem, and becomes 'our' problem."