The lengths countries go to for a seat at UN top table

- Published

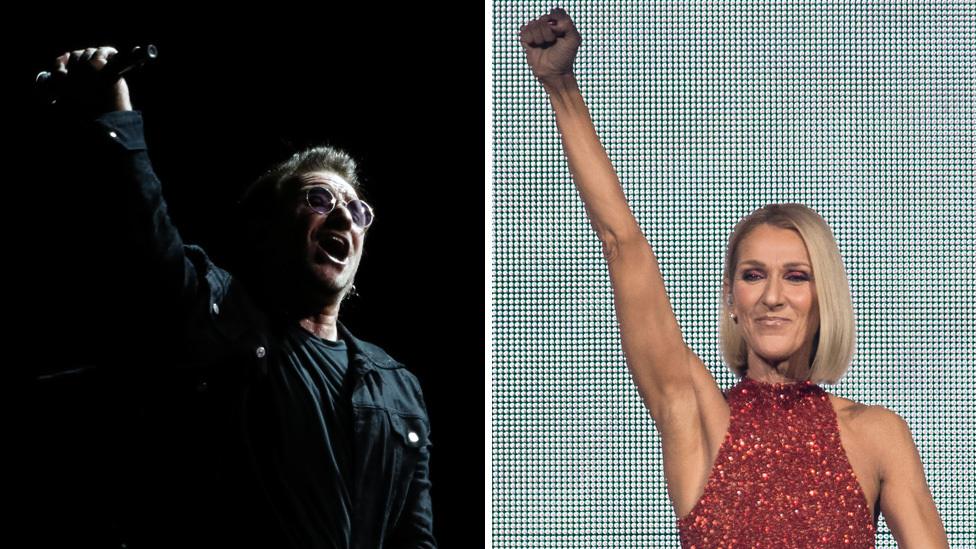

UN diplomats were treated to tickets to U2 and Celine Dion concerts

Glad-handing, parties and concerts by U2 and Celine Dion - how countries campaign for a seat on the United Nations Security Council.

It likely won't come down to the gift bags or the parties but that doesn't mean Canada, Norway and Ireland are leaving it to chance.

From Norway, General Assembly delegations will get a badge covered with fabric from the tapestry used to decorate the council chamber's walls.

Canada is offering greeting cards, chocolates, and Canada-branded facemasks.

The small tokens for delegations ahead of the 17 June vote come after lengthy campaigns by the three nations for one of two coveted non-permanent seats up for grabs on the security council, which is tasked with ensuring global peace and security,

The seats they are campaigning for are set aside for the "Western Europe and Others" [WEOG] regional grouping on the council.

The winners will serve a two-year term on the 15-member body.

*There is some strong language at the end of this article*

The UN General Assembly chamber in New York City

Campaign season for the contested seats means "a lot of parties, a lot of events" at the UN's headquarters in New York, says Stephanie Fillion, a journalist who covers the global body for news site PassBlue.

Campaigns can be elaborate affairs with slick promotional materials and plenty of wining and dining, and countries announce they will run years in advance.

In 2018, Ireland invited diplomats to a New York concert by Irish rockers U2, and Canada did something similar for a concert by Canadian songstress Celine Dion this year.

Canada says it's shelled out roughly $1.74m (£1.37m) and has 13 full-time staff working on the campaign. And as of late last year, Ireland spent a reported $800,000 and Norway $2.8m.

Why do countries want a seat on the council?

Member states get three things in return for a seat, says Adam Chapnick, a professor of defence studies at the Royal Military College of Canada.

Those are access, relevance and influence.

"For two years, day in and day out, a country that is not a great power will have direct access to the five permanent members in addition to whomever else might be on the council at that time," he says.

He adds: "With that access comes relevance."

Campaign events are held at the UN headquarters in New York City

"All of a sudden you're really popular around the world because if somebody else can't reach the Chinese or the Americans or the French, they know you can."

The council has significant responsibilities. It can authorise peacekeeping operations, impose international sanctions, and determine how the UN should respond to conflicts around the world.

But the council isn't always in the mood to collaborate, says Mr Chapnick.

"There are times when you can actually change the international rules of the game and there are other times where you absolutely can't. And that's entirely unpredictable."

Why Canada's bid is being closely watched

In 2010, Canada suffered its first ever defeat for a seat on the council. Portugal, a small European nation in economic turmoil at the time, pulled off an upset victory, and Germany won the other open seat.

In Canada, that defeat became a political debate, with opposition parties blaming the then governing Conservatives for what they saw as an embarrassing failure.

"In some ways the Portuguese won, in other ways Canada lost," says Mr Chapnick.

Portugal not only ran a strong campaign but actively campaigned against Canada, recruiting allies against its bid.

Canada's bid did have flaws, he says, including getting serious about the campaign late in the game. It also faced scepticism from African delegations after closing some embassies on the continent.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spent time in Senegal in February

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's Liberals later vowed the party would rectify that unsuccessful bid, announcing Canada was "back" on the world stage.

So how is this campaign shaping up?

Good campaigns usually have a few things in common, says Mr Chapnick.

Contenders will have a well-regarded representative at UN headquarters in New York, one with a close relationship with his or her home capital.

The campaigns are well-funded and often have an engaged head of government or state, or senior cabinet members, involved in the pitch.

Mr Trudeau has spent part of this year on the campaign trail, trying to secure votes from Caribbean and Africa countries during February overseas trips. He recently co-hosted a UN panel on the coronavirus pandemic. Mr Chapnick says it's positively viewed when competing nations show a commitment increasing their international engagement.

Norway, Ireland and Canada are all pitching their commitment to matters like climate change, multilateralism and peacekeeping.

Ireland is pushing the idea that "you can get everything you need from choosing a middle power like Canada or Norway" so the small island nation of Ireland brings a unique voice to the table, he says.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

He sums up Norway's broad line as "Canada says we're back, Norway says 'we never left'".

Canada has shifted its message in recent months during the pandemic, to "in a time of global crisis it's helpful to have another G7 country at the table".

Ms Fillion says: it's "important to keep in mind when you look at the vote is there is so much that countries take into account in order to cast their ballots".

It could be a strong bilateral relationship that one campaigning country's managed to build with a counterpart.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

There are also vote swaps, when one country will support a bid in return for a favourable vote for a seat on another UN body.

Recent elections have been less focused on international reputation - countries do highlight contributions to development aid and peacekeeping operations - and more transactional in nature, says Mr Chapnick.

It's "I don't care how much foreign aid you provide, how much of it goes to me".

All the factors coming into play makes the results difficult to predict, says Ms Fillion, though she has heard talk that either Norway or Ireland are currently in the lead.

Canada, distracted early on by the election of US President Donald Trump and subsequent free trade renegotiations with the US and Mexico, seems to have rallied in recent months, she says.

Not all regional seats are contested races - many groups run slates. In the last decade, nearly 80% of elections for council seats went uncontested.

Mr Chapnick is critical of the members of the Western Europe and Others group for competing for the seat as a rule instead of reaching some sharing agreement.

He says it's "not in anyone's interests" to have multiyear campaigns where countries "have to go shill all sorts of countries that aren't friendly to us" for a seat.

What can we expect from this vote?

There are five permanent members - China, France, Russian, the UK, and the US - and 10 non-permanent members. Elections for five seats are held every year.

Non-permanent members include two WEOG members, five Asian or African members, two Latin American members, and one east European member.

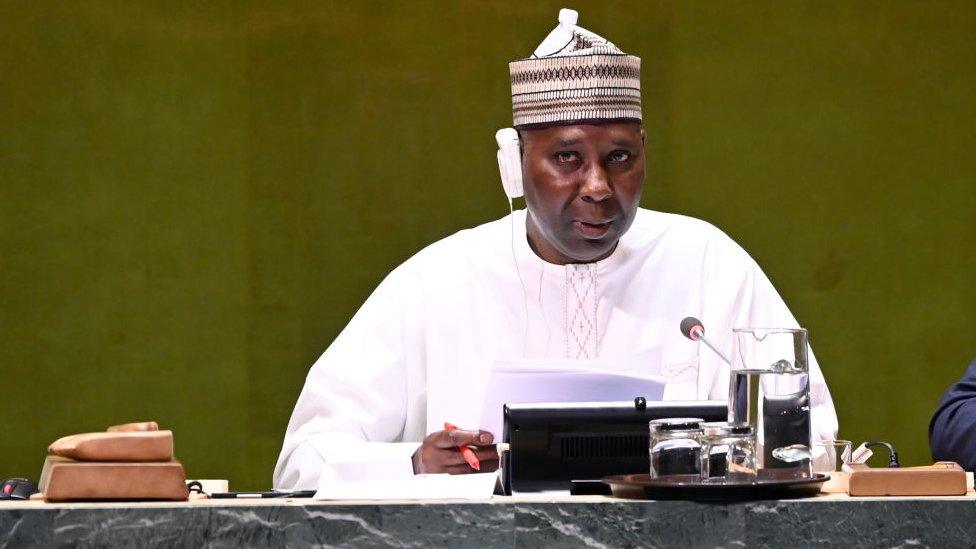

President of the UN General Assembly, Tijjani Muhammad-Bande, will oversee the socially distanced vote

Due to the coronavirus pandemic member states will not be in the General Assembly hall during the elections but will instead each be given a time slot to cast their secret ballot.

To win a seat, a country needs to secure the support of at least two thirds of the General Assembly delegations that are voting.

In the past, countries thought they had secured a seat only to find once the secret ballots are cast, promises of support never materialised.

A former Australian ambassador to the UN dubbed it the "rotten lying bastards" phenomenon after losing a bid in the 1990s.

- Published3 July 2018

- Published23 April 2019

- Published14 March 2019