George Floyd death: Seven solutions to US police problems

- Published

Protesters across the US have taken to the streets in the wake of George Floyd's death to demand an end to police brutality and what they see as systemic racism.

In response, Democrats have proposed legislation to address inequities and reduce deaths in custody, including measures that would require police to wear body cameras, ban chokeholds and make it easier to prosecute officers.

Here's a look at some of these proposed solutions, and other potential ways to reform policing.

1. Rewrite "use of force" policies

Most police departments have a "use of force" policy which dictates how and when officers can use force. These policies vary substantially from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, the type of "neck restraint" or chokehold that Officer Derek Chauvin used on George Floyd has been banned in New York City since 1993.

After high-profile police killings, many departments are forced to re-examine and rewrite their use of force policies by federal consent decrees. The city of Baltimore revamped its policy in 2019 as a part of its consent decree with the US Department of Justice after the death of Freddie Gray. The new version requires officers to report use of force incidents and compels them to intervene if they see another officer improperly using force.

After Floyd's death, the Minneapolis city council forced the police department's hand by banning chokeholds and making it mandatory for officers to intervene if their colleagues are using improper force.

Advocates acknowledge that simply rewriting these policies would not effectively prevent deaths like Floyd's, and that force is still disproportionately used against communities of colour. A New York Times analysis, external showed that the Minneapolis police use force against black residents seven times more often than white residents.

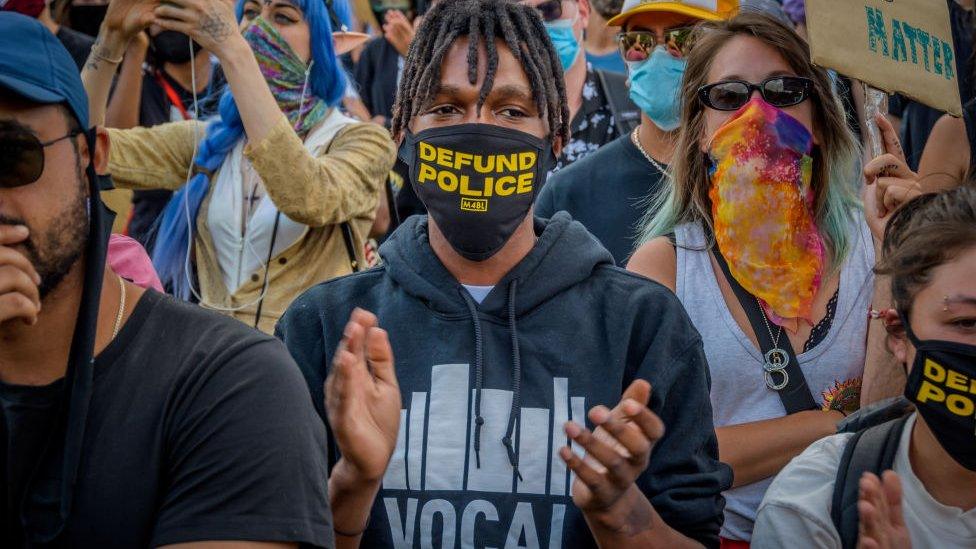

2. Defund the police

Protesters believe that cities and states spend far too much money on their police departments without sufficiently funding education, mental health, housing and other community-based social services. A growing demand is for political leaders to "defund" the police - that usually means reducing funding not cutting it altogether.

These calls have been heeded by the mayor of Los Angeles, who slashed $150m from a proposed budget increase for his city's police. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio also pledged to divert money from the NYPD towards social services, though he did not cite a figure.

NY Governor Cuomo: 'This has to be a fundamental rethinking' of police tactics

In Minneapolis, a group called the Black Visions Collective is asking the city council to pledge not to increase the police department's budget, and to divert $45m of the force's current budget to shore up the city's coffers in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

"Now is the time to invest in a safe, liberated future for our city," the group wrote. "We can't afford to keep funding MPD's attacks on Black lives."

3. Dismantle the police

On Sunday, a veto-proof majority of the Minneapolis City Council signed a pledge in front of a crowd of demonstrators promising to "begin the process of ending the Minneapolis Police Department". They vowed to create a "new, transformative model for cultivating safety". Earlier in the week, two council members used the word "dismantle" to describe their plans for the department, as did Minnesota Representative Ilhan Omar.

The statement did not make it clear if the council is merely pledging to remake the department, or if they were heeding some demonstrators' calls to "abolish the police," which would obviously be the most radical course of action. The council president said she could imagine a scenario where the department enters state receivership, and a team of medics and health care professionals respond to 911 calls, external instead of police.

A group called MPD 150 is calling for a "police-free future" in Minneapolis, in which mental health professionals, social workers, religious leaders and other community-based advocates would do the work of police.

There is some historical precedent for a wholesale dismantling of a department. In 2012, the Camden, New Jersey, police department was fully disbanded and all of its officers lost their jobs. However, it was certainly not abolition - a new, countywide police force was formed in its place, and about 100 former Camden officers applied for and regained their jobs. The move actually put more police on the streets of Camden. The new department adopted a very strict use of force policy and made it easier for the city to fire rogue officers.

The department has reported a steep decline in homicide and use of force complaints since.

4. Demilitarise

Since the 1990s, the military has transferred over $5bn-worth of equipment, ranging from sleeping bags to ammunition and armoured vehicles, to local police departments through a special acquisitions programme with the US Department of Defense.

As a result, many advocates for police reform argue that police today function more like domestic soldiers, using techniques and equipment designed for battle, than community peacekeepers trying to keep people safe, and that this approach costs lives.

President Barack Obama put limits on how police could use the programme in 2015, but most of those were overturned by the Trump administration a few years later.

Not only have police acquired more weapons over the past two decades, but many are taught military-style tactics. This so-called "warrior training" often spins a narrative where police are heroes fending off danger at every turn, who must learn how to protect themselves at all costs - even if that means killing civilians.

Critics say it teaches cops to be afraid, and to shoot first, think later.

In 2019, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey banned cops from attending "warrior-style" training, even on their own time with their own money. But the local police union called the ban "illegal" and continued to offer the training.

There is research to show that militarisation leads to police violence, external. In 2017, a study published in Research and Politics found that the more military weapons police have, the more likely they are to use them.

5. Sue the police

Citizens who try to sue the police in civil court for excessive force frequently see their cases thrown out because of a legal doctrine known as "qualified immunity". It was designed by the Supreme Court to protect government employees from frivolous lawsuits and give police legal breathing room surrounding their split-second decisions.

In order for a case to move forward, the court directs that it must ask two questions: first, was excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment used? And if so, is there a "clearly established" prior court ruling on the behaviour that would mean the officer knew his or her conduct was illegal?

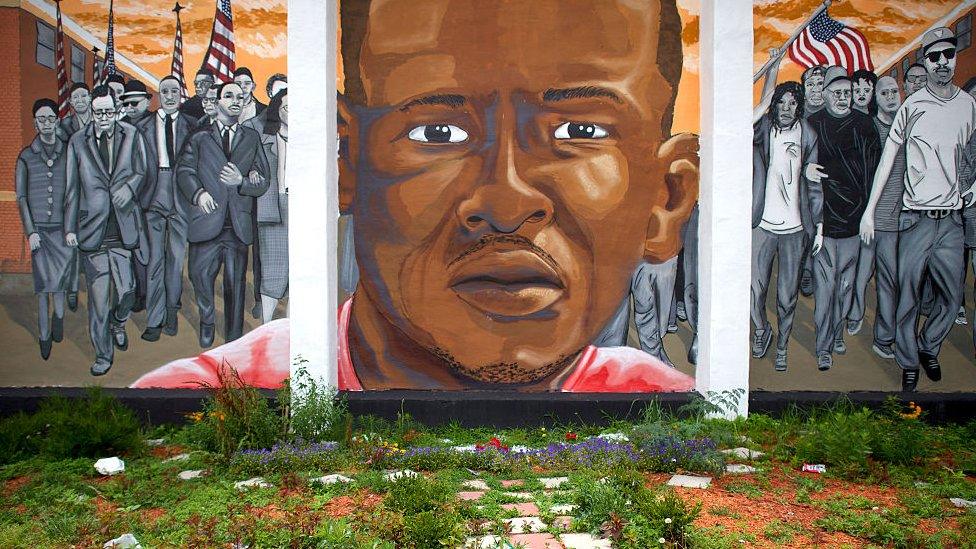

Freddie Gray's death in 2015 sparked protests and led to some reforms in the Baltimore Police Department

This second question is where advocates say courts give officers a free pass, throwing out cases if there has been no previous, precedent-setting case with an almost identical set of facts. A Reuters analysis found that more than half of excessive force cases in the US get thrown out, external on "qualified immunity" grounds.

A portion of the sweeping Justice in Policing Act introduced this week by House and Senate Democrats would eliminate qualified immunity for police. Supreme Court Justices Sonya Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas have both said they believe the doctrine needs to be revisited. There are currently eight qualified immunity cases before the country's highest court.

6. Police the police

Sometimes, police violence against black people is attributed to a "bad apple" - an angry and racist cop who overreacts in the line of duty.

In an effort to keep them out, some forces have fired police officers who publicly admit to racist ideas. Last July, the Philadelphia Police Department fired 13 officers, external who posted racist, violent messages on social media - but only after an advocacy group brought the messages to light

Eric Garner's mother speaks outside of George Floyd's visitation

But the reality is a bit more complicated than just one bad apple ruining the bunch.

Police work in what social researchers call a "closed system" where there is little external oversight and loyalty is highly prized. If one officer crosses the line, others will back him or her up. Without a video of the incident, it often comes down to just the word of an alleged "criminal" and a respected police officer.

That's why many are pushing for police to be required to wear body cameras, to record police interactions. They were adopted in New York a few years ago after the death of Eric Garner, external, and Congress is proposing making them mandatory nationally.

But there is little evidence that shows they reduce violence, external, according to a recent analysis of 70 studies looking at their efficacy.

Campaign Zero, the non-profit behind the #8cantwait hashtag pushing for police reforms, says they have limited use. While footage of police brutality has played a vital role in exposing the problem, external, most of it was filmed by citizens, not police. Body cameras can easily be turned off, and the footage is more likely to be used by prosecutors against civilians during criminal trials, than as a means of proving police brutality.

7. Start counting

There is no doubt that black Americans are more likely to be killed by police and subjected to other forms of police violence. But what's still unclear is exactly how many victims there are, or which departments are the worst offenders.

In 2014, Obama signed into law the Death in Custody Reporting Act to force police departments to report every time a citizen dies in custody. The law also required the data to be turned over to the attorney general, who would have to release a report on ways to reduce deaths every two years.

Four years later, the Department of Justice's inspector general said the department still had no mechanism to collect data from the states, external and didn't expect to have one until 2020.

Meanwhile, the FBI has launched the National Use-of-Force Data Collection, external project, to track not only people killed by police but every time a police officer uses force. They began collecting this data in 2019, but local law enforcement agencies are not required to participate and the information has yet to be made public.

The history of police violence in the US

In this vacuum, non-governmental organisations and journalists have had to fill in the gaps. In 2015, The Washington Post began to log every fatal shooting by an on-duty police officer in the US. Since then, they have recorded more than 5,000 people killed by police, using a mixture of news reports, social media and police reports. Their data, which is often used by policy researchers, shows that black people were almost 2.5 times more likely to be killed, external than white people.

(Additional reporting by Jessica Lussenhop)