Coronavirus: The last-round fight for NYC's bastions of boxing?

- Published

Some of New York City's most iconic boxing gyms have been forced to close because of the coronavirus pandemic, and with no official guidance on how they can reopen, many gym owners fear the city will forever lose this sporting legacy, writes Ben Wyatt.

Former featherweight champion Heather 'The Heat' Hardy stands on a Brooklyn street corner dressed in workout gear.

She has boxing mitts in her hands and a pair of gloves around her neck. As masked pedestrians walk along the sidewalk she tries to persuade them to join an impromptu training session on the sunshine-baked tarmac.

Boxing has always been a tough career, but at the age of 38, and as a single mother of a 16-year-old daughter, the streets that forged Hardy are now proving her only refuge.

Like all journeyed fighters, she talks a good game: "In New York City we work paycheque to paycheque, you know.

"I was born and raised in Brooklyn. I always figure out a way. I'll get through this too."

Heather 'The Heat' Hardy tries to encourage passers to workout with her

But her optimism belies the fact that her neighbourhood gym of Gleason's - a cultural and pugilistic icon of the city that's also the source of Hardy's private training income, her big-fight coaching team and her closest friends - has been closed by the state since March with no pathway to reopening.

"You miss the jokes," she says of her fellow fighters, who before the pandemic trained and taught in the gym up to 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Other opportunities have been missed too. The two fights Hardy had booked for this year, one of which was a title shot, were cancelled as the outbreak gathered pace.

Without savings to spend or workout classes to supplement her income, Hardy's street hustle is her best hope.

It's a far cry from her last fight at Madison Square Garden, where she suffered the first defeat of a gutsy 23-fight career, losing to interim world champion and fellow Brooklynite Amanda Serrano in an internationally televised match.

Fights overseas are returning, but without access to her coaches or a ring she will be forced to consider bouts for which she'll be dangerously underprepared.

Hardy's story personifies the plight of pro boxing in the Empire City in 2020.

How one personal trainer is going online during the pandemic

Madison Square Garden's position as the sport's first mecca made New York an epicentre for the sweet science in years gone by, but from a heyday-high in the 1920s there's been a steady decline with each passing decade.

Of the 25 professional gyms that existed across the five boroughs in the 1970s, only a handful remain.

These glitz-free, idiomatic churches of sweat and sparring - where age-old ring knowledge nurtured colossi such as Sugar Ray Robinson, Jake LaMotta and Riddick Bowe - were already on shaky legs prior to lockdown.

Their enforced closure, without an end in sight or mention in the state's phased reopening measures, means they are all now on the precipice.

Gleason's gym is a famed boxing landmark

Bruce Silverglade, the former president of amateur boxing in New York and owner of Gleason's for 37 years, argues that at a time of their greatest need, boxing is being discriminated against by politicians choosing to look the other way.

He's watched other professional sports franchises such at the NBA, Major League Soccer and Major League Baseball receive government guidelines on how to train and eventually resume play, while boxing has been left in the dark.

In boxing, where individuals have no leagues, federations or expensive attorneys to speak on their behalf, Silverglade argues the fighters of the city should be allowed to resume behind-closed-doors training at the very least. It's a lifeline that could prevent the extinction of the culture and its gladiators.

"If the governor or the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] were to give me directions, I'd adhere to them," says Silverglade.

"I have no idea when I can reopen, why I'm closed, or when I can earn a living again. Gyms in other states are open. List your objections, so I can take care of them."

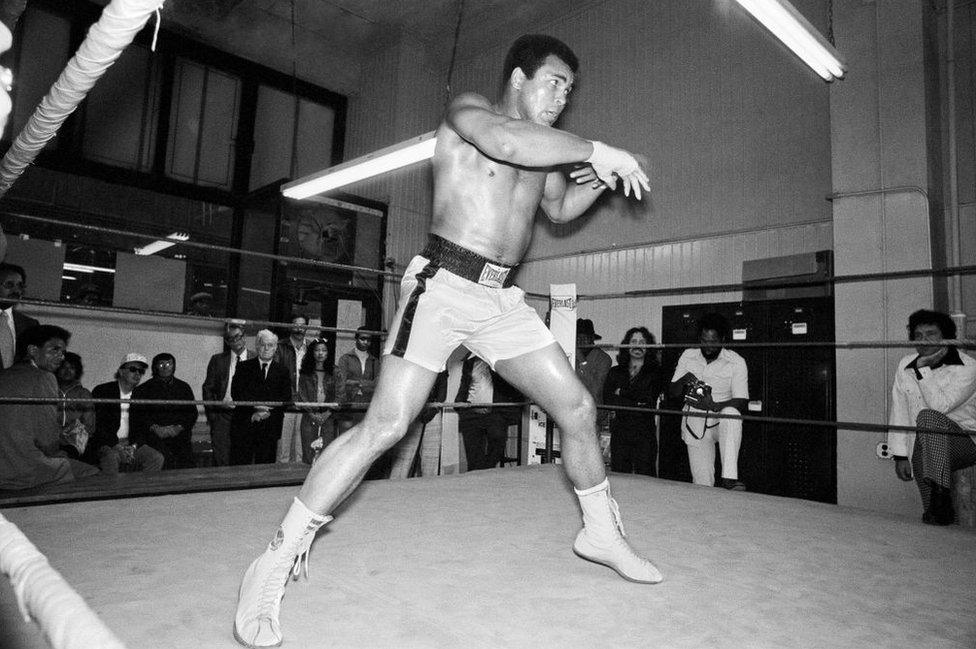

Muhammad Ali trains at Gleason's before a championship bout in 1976

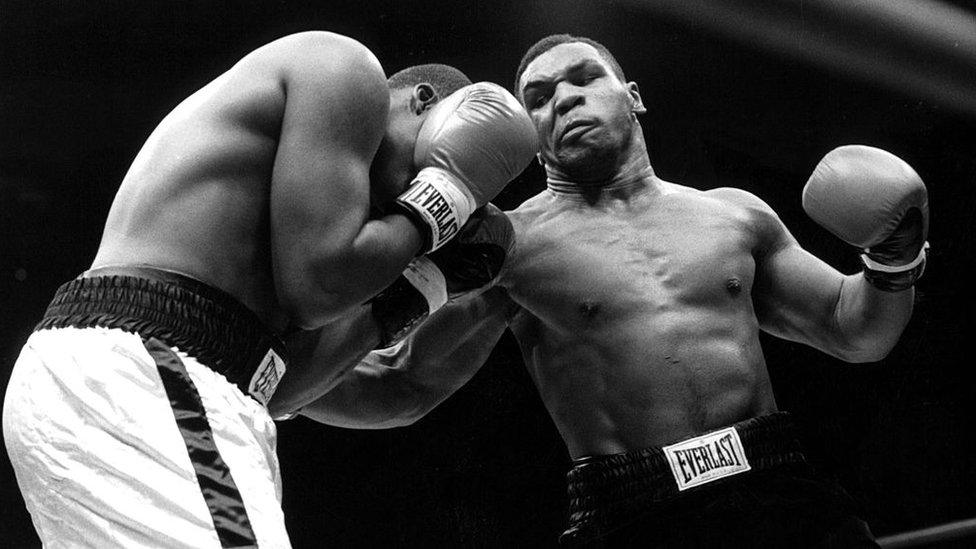

Originally based just one block from Madison Square Garden, Gleason's moved to Brooklyn in 1987, schooling local talent such as the young Mike Tyson in the process.

As the USA's oldest boxing gym, it's welcomed everyone from Muhammad Ali to Paul Malignaggi, and there were times in the 80s when all five of its rings would creak from the sparring of world champions.

The clientele slowly evolved, with hobbyists accounting for 85% of members by the turn of 2020. Up until March, this income flow supported 92 trainers and eight staff. Now, most of the coaches are surviving on unemployment benefits.

"Today, I made 40 bucks selling two t-shirts. Last week I made 120 bucks selling a pair of gloves," Silverglade says of his earnings from the last month.

"I've still got to pay rent and insurance and I've spent thousands on PPE equipment."

Mike Tyson (right) boxed at Gleason's as a child

Worryingly, Gleason's is faring better than most in lockdown. The Fight Factory gym, located near the boardwalks of Coney Island and Brighton Beach, closed at the end of June after 11 years in business.

Former soldier Eugene Ryvkn built the gym with help from local pro Dmitry 'Star of David' Salita after moving to New York in 1997 from Belarus. Having notched up 60 amateur fights back home, Ryvkn fought on in the US until he was 45; sparring in his gym until its last day.

Ever mindful of his 165lb (75kg) fighting weight, the already slim Ryvkn, 50, has shed 15lbs since the closure.

"I didn't sleep well, in like three months, because everything in my head. The rent, the business, everything, everything. I built it from scratch myself. I invested a lot of money in this place," he says.

"I had three full size rings, wrestling mats, weights area. An area where parents could do homework with the kids after school. I tell you, there's no more American Dream here, no more dreaming."

The Brighton Beach-based Fight Factory before its closure in March

He applied for loans but found that he was ineligible for emergency funding due to the part-time nature of his coaches.

After regularly housing pro boxing names such as Bakhtiyar Eyubov, Nikita Ababiy and Arnold Khegai along with 250 local children from the ages of six and up, the remnants of The Fight Factory is now functioning within a rent-free home in a local synagogue, contemplating how it might serve its largely Russian immigrant community in the future.

Across the East River, the story is similarly critical.

Marc Sprung, the owner of Church Street Boxing, initially moved his operations online, paying his coaches to host Zoom training sessions while relying on recurring subscriptions to weather the 80% drop in income.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

CONTACT TRACING: 'He asked me: Am I going to die?’

MEETING FRIENDS: How can I do that safely?

TEENAGE RITUALS: Growing up, interrupted

SUPERSPREADERS: What makes some events so risky?

But when there was no further guidance from the state on how or when they might reopen, Sprung stopped charging fees and - with his staff's blessing and on the advice of lawyers - sacked his team so they would be eligible to file for unemployment benefits.

"It was very emotional, I've known these guys for over 20 years. If nothing changes we'll be closed in a month," Sprung tells the BBC.

"We could be looking at wiping out the fight culture in New York City."

Sprung is part of group that has launched a lawsuit against the state government demanding the inclusion of small, independent gyms in the plans for phase four of reopening. More than 300 gyms and workout studios have joined the lawsuit.

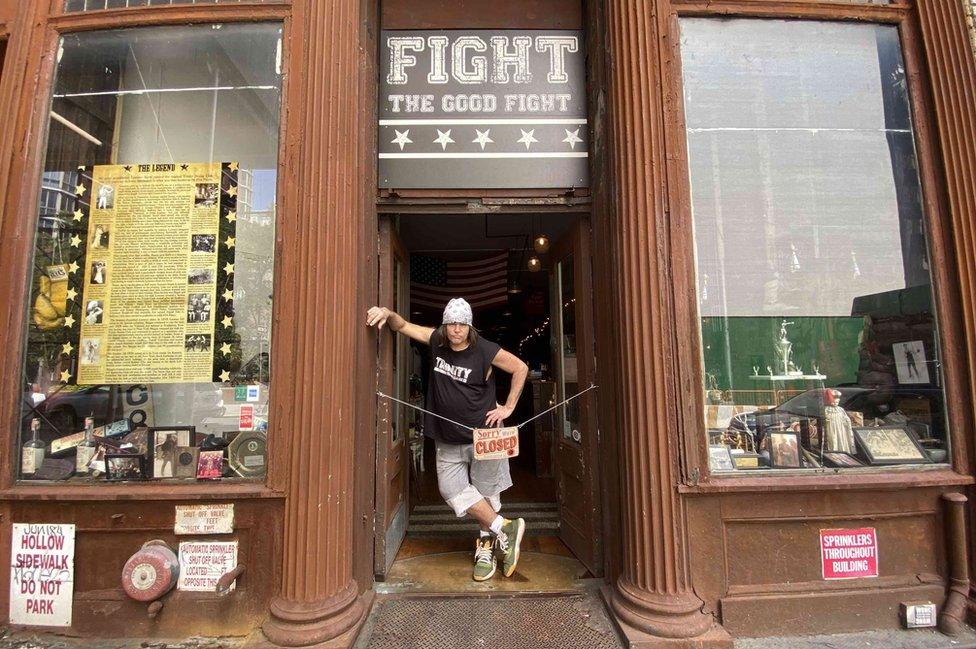

Martin Snow, owner of Trinity Boxing and former Golden Gloves super heavyweight champion

A few blocks from Church Street in Manhattan's financial district is Trinity Boxing, owned by former Golden Gloves super heavyweight champion Martin Snow.

A heavy-hitting slugger in his fighting days; the garrulous coach stands at the front of his gym under an entrance bedecked with two signs. The first reads: "Fight the good fight", the second: "Sorry, we're closed".

"Why can they train in California but [we] can't do it in New York? Do they know something we don't know?" he says.

Without the greater resources of beginner-friendly boxing chains such as Rumble and Title, Snow feels the independent pro gyms - traditional havens for "the outcasts and the disenfranchised, the immigrants and the working class" - are particularly vulnerable. Even the city's sex clubs have been allowed to reopen before a road map for boxing facilities have been discussed, he adds.

"You can have socially-distanced orgies with hand sanitiser and masks, but you can't go into a boxing gym? That's f—king nuts. So I decided, I'm going to have boxing orgies: only with no sex, three minutes a time, fully clothed, wearing boxing gloves and head-guards."

You may also like:

It's not just income that's being lost in the crisis but leaders too. As one of the legion of immigrant boxing enthusiasts in the five boroughs, Mexican-American Francisco Mendez opened the Mendez Gym on East 32nd Street in 2004. It became one of the city's leading locations for novices and champions alike.

Sadly, Mendez died on 21 April because of Covid-19 related complication.

Ultimately, the gyms may take up opposing corners come fight night but are united in their time-of-crisis message.

"New York boxing is the forgotten sport," says Hardy. "Promoters are calling on New York fighters because they know we're not training. [Governor] Cuomo, don't let us be the underdogs, man."

Follow Ben Wyatt on Twitter @benwyatt78, external

- Attribution

- Published8 July 2020

- Attribution

- Published9 July 2020