Jacob Blake and Kyle Rittenhouse: Should police have used different tactics?

- Published

Two incidents have turned Wisconsin into the latest epicentre of America's police protests. What can the footage from two different shootings tell us about US policing?

The first saw Jacob Blake, a 29-year-old black father, shot several times by a white officer, leaving him paralysed in hospital. The second followed in the unrest sparked by Mr Blake's shooting, where white 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse allegedly shot and killed two protesters.

We asked two law enforcement experts for their take on the viral footage: New York Law School criminal law Professor Kirk Burkhalter, who served 20 years in the New York City Police Department, and Brennan Center national security fellow Michael German, who was an FBI agent for 16 years.

First, let's break down the two videos.

What do we see in the Blake video?

In a bystander-filmed clip of the police shooting, Mr Blake is seen walking around to the front of his vehicle. One of the two officers following him at this point has a weapon drawn. It is unclear what the police officers said before the shooting.

Blake opens the door and leans into the car. The officer grabs his shirt and opens fire. The other officer also draws his gun.

Seven shots can be heard in the video, as witnesses scream.

Just before the first video that was released begins, police reportedly wrestled and tased Mr Blake. Investigators said a knife was later uncovered from the floor on the driver's side of Mr Blake's car.

What can we see in the Rittenhouse videos?

Mr Rittenhouse has appeared in a number of different videos from Tuesday night's Kenosha protest. In one, he speaks to police, who offer him water.

Later, he is seen in footage running from a group of people, one of whom appears to fire into the air.

Mr Rittenhouse appears to shoot a man who tries to assail him. As he flees and is chased again, he falls to the ground and shoots again. A man falls to the ground, and many shots can be heard.

Two people were killed and one injured on the third night of unrest

Following this incident, Mr Rittenhouse approaches police vehicles with his arms in the air, his weapon slung across his chest.

A bystander calls out that the teenager "just shot" people, but the police vehicles pass by to attend to the injured protesters.

Should police have responded differently?

With Jacob Blake...

While there is no specific rule for every single scenario, both experts note that as far as we know, Mr Blake was not being arrested or wanted for any heinous crime (like mass murder).

The whole encounter played out in around seven seconds.

"The effort to prevent him from getting into his car and driving away is what led to the violence," says Mr German. "They had his licence plate number, if they needed to go arrest him later, he would be easy to find."

Prof Burkhalter adds that in the moments leading up to the shots, officers "passed through several decision points where, arguably, they could have made more effective decisions", like tackling him or tasing him again.

"When someone resists arrest and they attempt to walk away, which happens often...that in and of itself is not carte blanche to use deadly physical force, period."

The retired detective adds that if Mr Blake threatened deadly force, drawing weapons could be justified. But he says it's "particularly disturbing" that an officer grabbed his shirt with one hand and fired with the other.

"It didn't appear to be life threatening at that particular point and holding someone in place so you can shoot them, unless they are actually armed at that time, seems wildly problematic."

There's also a lack of situational awareness, Prof Burkhalter points out, calling it "an absolute miracle" that none of the seven shots ricocheted to strike the children in the car.

...and Kyle Rittenhouse?

Prof Burkhalter begins: "It is absolutely ridiculous that, confronted with this person, the police would not take action."

Rendering aid, he says, is of course the number one priority.

"However, there were a significant number of police officers on this street. I would guess that some of those officers could have rendered aid and others could have pursued this man."

And as Mr German notes: a rifle shot is loud. For officers to respond and see anyone walking towards them with a rifle is a "serious violation of police safety protocol".

"To let that person go behind the police line is astonishing," he says.

How do the responses compare?

There are clear differences for Prof Burkhalter. One man who may or may not have been reaching for a knife was "corralled, [an officer] holding his shirt like he's some type of animal" and shot multiple times, he says, while the other was walking down the street with an assault weapon.

But while a lot of emphasis is placed on the actions of a single officer, Prof Burkhalter says "there's often a lot of blame to go around". In both incidents, he asks: "Where is the supervisor who was responsible for these actions?"

Letting an armed individual walk behind the line of cars "is astonishingly dangerous for the police officers themselves," Mr German points out.

These two incidents highlight the ways "police are trained to be afraid of certain situations and not others," he says.

The first shooting took place in broad daylight on a residential street. The second, in the middle of the night in a chaotic civil unrest environment.

"The situations are just so opposite in how the police should have responded compared to how they did."

So how should police training change?

Mr German criticises the development of a "warrior cop mentality" in the last two decades - the idea "that police officers in their daily work are at extreme threat from the communities they serve and...treat every incident as one that could end their lives".

He says research shows that fear of death creates a mind-set that "demonises out-groups". Acknowledging the existence of conscious biases and racism will be key to reforming US law enforcement, he says.

And there's another problem Mr German - who did undercover work with far-right groups - has seen play out in recent years.

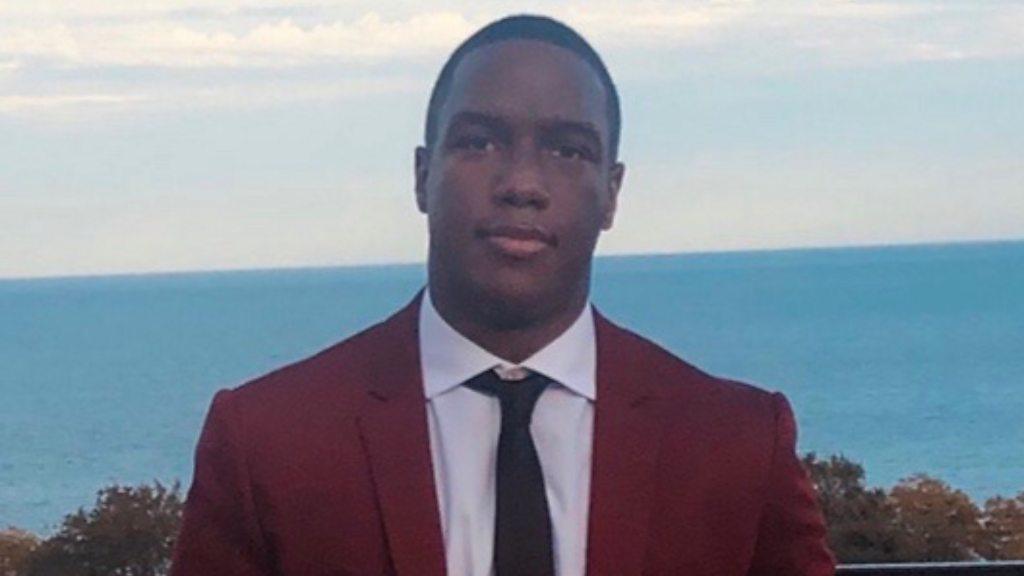

Myron Grant started therapy after the events that have shaped 2020 started to take a toll on his mental health

White supremacist groups and armed militias have been seen interacting with police at protests. "It's astonishing that even at the leadership level, they don't recognise the danger they're putting their officers in by suggesting those far-right militants aren't the bigger threat," he says.

For Prof Burkhalter, it's time to throw out the book on policing altogether, and pen a new one for the 21st century.

In lieu of six-month academies, he suggests officers have a more undergraduate-style training: two years where trainees learn from department personnel and civilian academics about history, psychology, immigration law, sociology, and participate in on-the-street training with guided reflections.

Policing standards should also be set at the national level, and there should be a national registry. Pay increases could also help attract a wider range of prospective candidates, he adds.

With this dream in mind, Prof Burkhalter thinks the movement to defund the police - that is, to cut police funding and redistribute money to social programmes - "would only compound the problem".

"Revising departments and the training, the education that I'm talking about - that requires funding."

- Published24 August 2020

- Published21 April 2021

- Published22 April 2021