US election 2020: The night American democracy hit rock bottom

- Published

When the first televised debates were held in 1960, the world watched two young candidates, John F Kennedy and Richard Nixon, respectfully engage in an intelligent and elevated discussion.

Mostly we remember those inaugural encounters for Nixon's flop-sweat and clumsily applied make-up.

But in the midst of the Cold War, as the ideological battle raged between Washington and Moscow, the debates were seen as a thrilling advertisement for American democracy.

Speaking in the spirit of patriotic bipartisanship that was such a hallmark of US politics in the 1950s and early-1960s, Kennedy opened the first debate with an eye on how it would be viewed by international onlookers:

"In the election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln said the question was whether this nation could exist half-slave or half-free. In the election of 1960, and with the world around us, the question is whether the world will exist half-slave or half-free, whether it will move in the direction of freedom, in the direction of the road that we are taking, or whether it will move in the direction of slavery."

Tuesday's vicious encounter, more cage-fight than Camelot, spoke of a different era and a different country: a split screen America, a nation of unbridgeable divides, a country beset by democratic decay.

Two elderly men, both of them in their 70s, traded insults and barbs, with a sitting president once again trashing in primetime the norms of conventional behaviour.

If there is such a thing as a heavenly pantheon of former presidents, an Oval Office in the sky, Abe Lincoln and Jack Kennedy must have peered down like baffled ghosts.

To many international onlookers, to a large portion of Americans as well, the debate offered a real-time rendering of US decline.

It reminded us once more of how American exceptionalism has increasingly come to be viewed as a negative construct: something associated with mass shootings, mass incarceration, racial division and political chaos.

"Shut up, man" and other insults and interruptions

Germany's Der Spiegel called it "A TV duel like a car accident".

"Never had American politics sunk so low," lamented Italy's La Repubblica's US correspondent.

Le Monde, the French newspaper that declared "nous sommes tous Américains" - "we are all Americans now" - in the aftermath of the attacks of September 11th, called it a "terrible storm".

But storms pass. What the debate showed last night was America's permanent political weather system.

At a time when geopolitical soft power has assumed such importance, and where influence is intertwined with international image management, the 21st Century has produced some searing images of American self-harm.

The Florida election debacle in 2000, when we woke after Election Day to polling stations sealed off with yellow police tape, presented a sorry democratic spectacle.

At one point, as the recount became ever more farcical, the Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe even offered to send over election observers. When the conservative-leaning Supreme Court intervened in favour of George W Bush, it looked like an electoral smash and grab.

The 2000 recount tore the country apart

Then there was the damaging imagery of the Bush administration's war on terror - the watchtowers of Guantanamo, the horrors of Abu Ghraib and the imperial hubris of that "Mission Accomplished" banner, the backdrop for the made-for-television moment when George W Bush prematurely claimed victory in an unfinished war that ended up haemorrhaging so much American blood and treasure.

Future historians will place Tuesday night's television horror show in that same picture gallery of national embarrassment.

Many international viewers also comprehend the analytical prism through which the debate has to be viewed - that Donald Trump's base sent him to Washington precisely because of his unconventionality, and that supporters will regard criticism of the president's aggressive style as elite condescension.

Fans of his destructive energy tuned in to watch a political WrestleMania, the smack-down of Joe Biden. That now is widely understood.

But his failure to explicitly condemn white supremacists, and his strange words of advice to the far right group The Proud Boys, "stand back and stand by", still shows his capacity to shock.

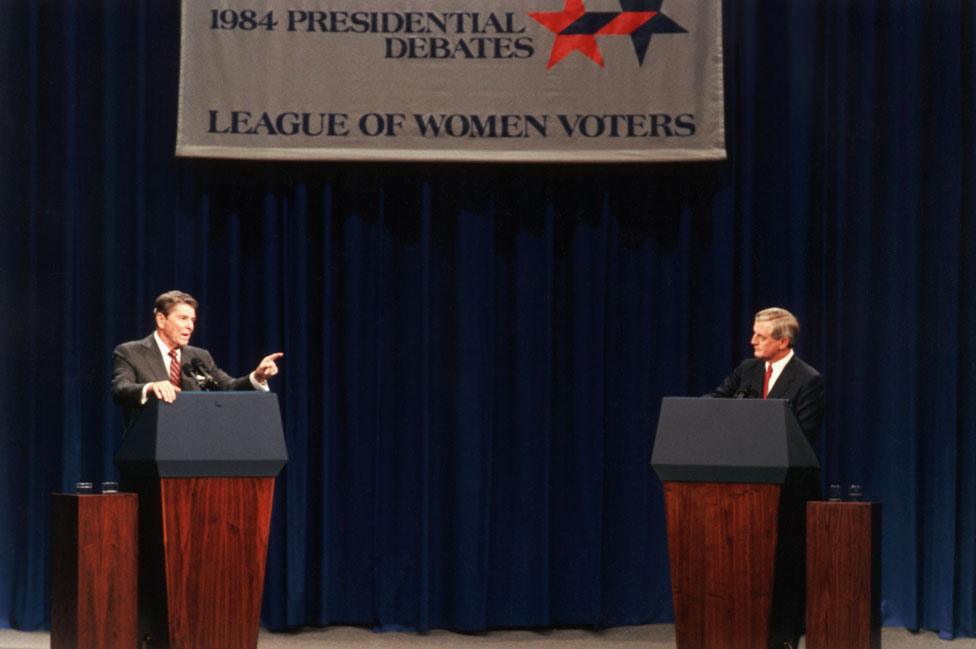

After the inaugural television debates in 1960, there was a 16-year pause before we saw them return again.

Then the first debate between Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter was marred by a technical failure, which killed the audio for 27 minutes - something that would have provided a welcome breather last night.

Now the format and even the future of these debates has come under renewed scrutiny, with the Commission on Presidential Debates announcing that "additional structure should be added to the format of the remaining debates to ensure a more orderly discussion".

Over the years, the presidential debates have become as much about entertainment as elucidation. As journalists we hype them like Vegas world heavyweight boxing bouts beforehand and score them like TV critics afterwards.

The highlights, inexorably, are the moments of combat and comedy. The prefabricated zingers. The caustic one-liners. The "knock out punches" - we have even adopted the vocabulary of ringside commentary.

Ever since Ronald Reagan mastered the genre, the debates have tended to reward star power over expertise.

Reagan was a natural for the TV medium

Presidential debates increasingly have come down to who can deliver Reagan-style one-liners, the jokes or putdowns that are rerun endlessly on the news in the days afterwards.

What is supposed to be a job interview has become more like an audition for the role of leading man.

Into this charisma trap have tumbled a long line of qualified but losing candidates - Walter Mondale, Bob Dole, Mitt Romney, Hillary Clinton, Mike Dukakis, Al Gore.

All of them were more accomplished administrators than actors.

Nor is it a coincidence that the only one-term president of the last 40 years, George Herbert Walker Bush, was terrible on television. Tellingly, the moment his time was deemed to be up was when he glanced impatiently at his wristwatch in the midst of a televised debate with Bill Clinton and Ross Perot.

That 1992 debate, the first ever to be held in the town hall format, showed how Bill Clinton, a telegenic young governor, had mastered the medium.

Effortlessly fielding questions from the audience, he displayed the stagecraft of Elvis and the empathy of Doctor Phil. In the age of Oprah, those all-important debate optics helped him win. Like Reagan, he became another performative president who understood the theatrical requirements of the part.

So as well as dramatising the electoral process, the televised debates have arguably ended up dumbing it down. Tuesday night hit rock bottom.

The cliché trotted out afterwards serves also as a truism: America was the loser.

- Published1 August 2020