Coronavirus: The place in North America with no cases

- Published

Covid-19 cases are rising in many parts of Canada, but one region - Nunavut, a northern territory - is a rare place in North America that can say it's free of coronavirus in its communities.

(Note:This story was written in late October. As of 8 November, Nunavut has confirmed two cases of the coronavirus in one of its communities, Sanikiluaq.)

Last March, as borders around the world were slamming shut as coronavirus infections rose, officials in Nunavut decided they too would take no risks.

They brought in some of the strictest travel regulations in Canada, barring entry to almost all non-residents.

Residents returning home from the south would first have to spend two weeks, at the Nunavut government's expense, in "isolation hubs" - hotels in the cities of Winnipeg, Yellowknife, Ottawa or Edmonton.

Security guards are stationed throughout the hotels, and nurses check in on the health of those isolating. To date, just over 7,000 Nunavummiut have spent time in these hubs as a stopover on their return home.

It's not been without challenges. People have been caught breaking isolation and have had stays extended, which has in part contributed to occasional waiting times to enter the some of the hubs. There have been complaints about the food available to those confined there.

But, as coronavirus infections spread throughout Canada, and with the number of cases on the rise again, the official case count in Nunavut remains zero.

The "fairly drastic" decision to bring in these measures was made both due to the population's potential vulnerability to Covid-19 and the unique challenges of the Arctic region, says Nunavut's chief public health officer, Dr Michael Patterson.

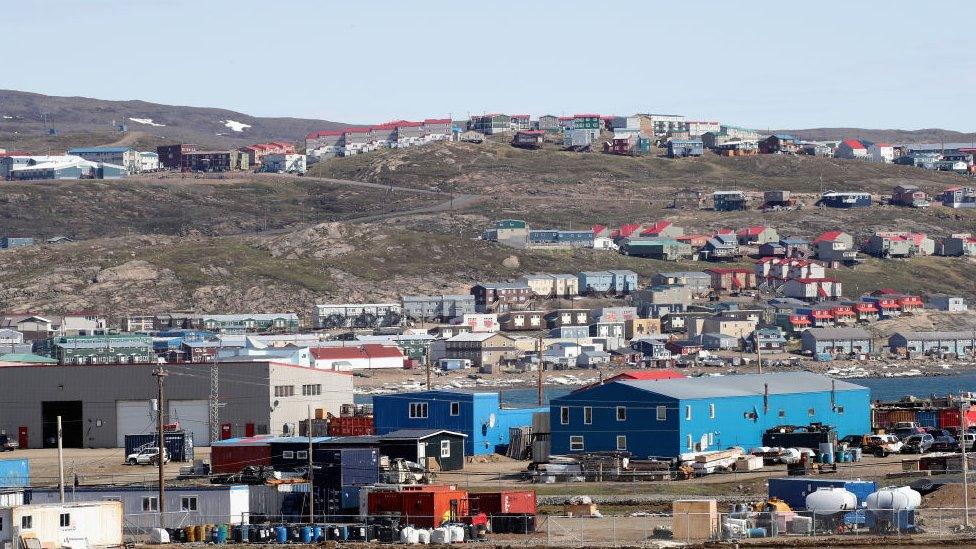

About 36,000 people live in Nunavut, bound by the Arctic Ocean to the north and the Northwest Territories to the west, in 25 communities scattered across its two million square kilometres (809,000 square miles). That's about three times the size of Texas.

The distances are "mind-boggling at times", admits Dr Patterson.

Natural isolation is likely to be part of the reason for the lack of cases - those communities can only be reached year-round by plane.

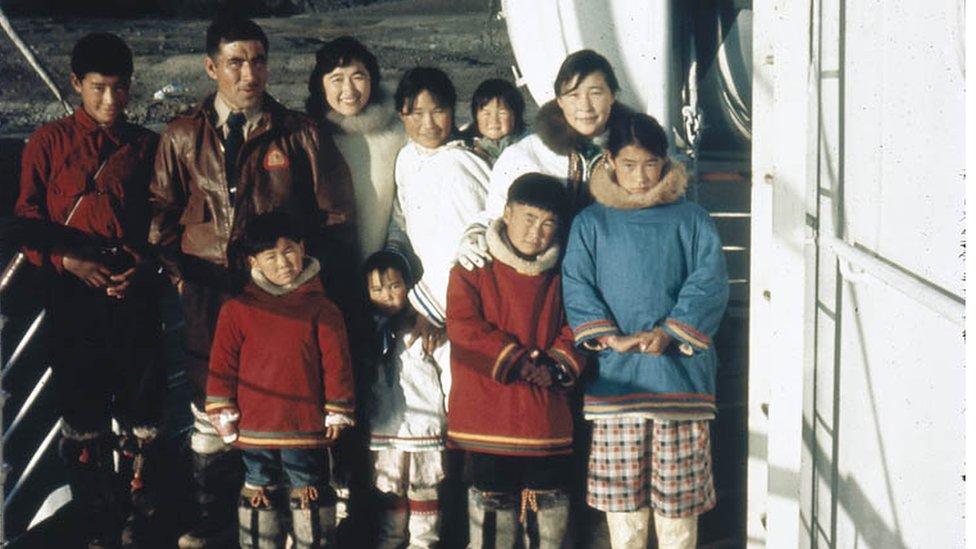

Over 80% of the residents of Nunavut are Inuit

In late September, there was an outbreak linked to workers who flew in from the south to a remote gold mine 160km (100 miles) from the Arctic Circle.

(Those cases are currently being counted as infections in the miners' home jurisdictions, keeping the territory's official case count at nil).

That outbreak has "almost no chance" of spreading in the community because there hasn't been any travel between the mine and any of the communities for months, says Dr Patterson.

But while isolation can help, it can also create hurdles.

Most communities don't have the capacity to do Covid-19 testing locally, so tests have to be flown in and out.

Early on, tests results could take a week, meaning "you're really, really far behind by the time you can identify and respond", Dr Patterson says. There are efforts under way to boost testing capacity and turnaround times for results in the territory.

There are also limited medical resources in the north. The 35-bed acute care Qikiqtani General Hospital in Iqaluit, the capital, could handle about 20 Covid-19 patients, Dr Patterson estimates.

In the case of an outbreak, "those people who need treatment, or need admission, many of them will wind up having to go south and so that will another load on our Medivac system".

Many Inuit communities - in Nunavut and elsewhere - are potentially at much higher risk.

There are a few factors at play, including inadequate and unsafe housing conditions and high rates of overcrowding, an all too common reality in the territory.

The high prevalence of tuberculosis is another concern.

Inuit, who make up over 80% of the territory's population, are a high-risk group in general for respiratory infections, including tuberculosis, says Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, a national advocacy group.

Inuit are nearly 300 times more likely to get tuberculosis than non-indigenous Canadians.

His own family experience with the respiratory illness brought home the potential dangers of Covid-19 for Ian Kanayuk.

The 20-year-old student and his mother came down with it a few years ago. He spent nine months on medication, his mother had a lengthy hospital stay.

Both are fine now but "it was really serious", he says.

So he's in favour of the social distancing measures, limits on gatherings, and the mask rules that are in place across the territory despite the lack of cases.

Frobisher Bay in Iqaluit, Nunavut

Dr Patterson says those are still necessary because "even though the hubs are there, the hubs aren't perfect". There are also some exemptions to the mandatory out-of-territory isolation, for example for certain critical workers.

So even with no community cases, the pandemic has touched the territory in ways that will be similar to people living throughout Canada.

Mr Kanayuk, like college students in many parts of the world, is disappointed to be studying remotely from his home in Iqaluit, and not in Ottawa, the national capital, where he had plans to attend in-person Nunavut Sivuniksavut, a programme for Inuit youth from across the country.

"It's disheartening to not be able to go down", he says. Then there's the added challenge that slow internet speeds in the territory place on remote learning.

The pandemic has also overwhelmed an already strained mail system, leading to frustrations over length queues to pick up packages.

Inuit children on Baffin Island

The Iqaluit post office was already one of the busiest in Canada, since so many residents depend on Amazon's free delivery to the Arctic city.

That post office has seen a spike in the number of parcels during the pandemic "beyond anything we could have anticipated", Canada Post said in a statement.

Since the strict measures came into force in Nunavut in March, there has been some relaxing of regulations.

With some conditions, Nunavummiut can now travel to the Northwest Territories and back without isolating, as can people going to Churchill, Manitoba for medical treatment.

But there needs to be measures in place to limit contagion when the virus does make its way to Nunavut, says Dr Patterson, who doesn't think it will be free of Covid-19 forever.

"No. Not indefinitely," he says, "I wouldn't have bet that it would stay this way for this long."

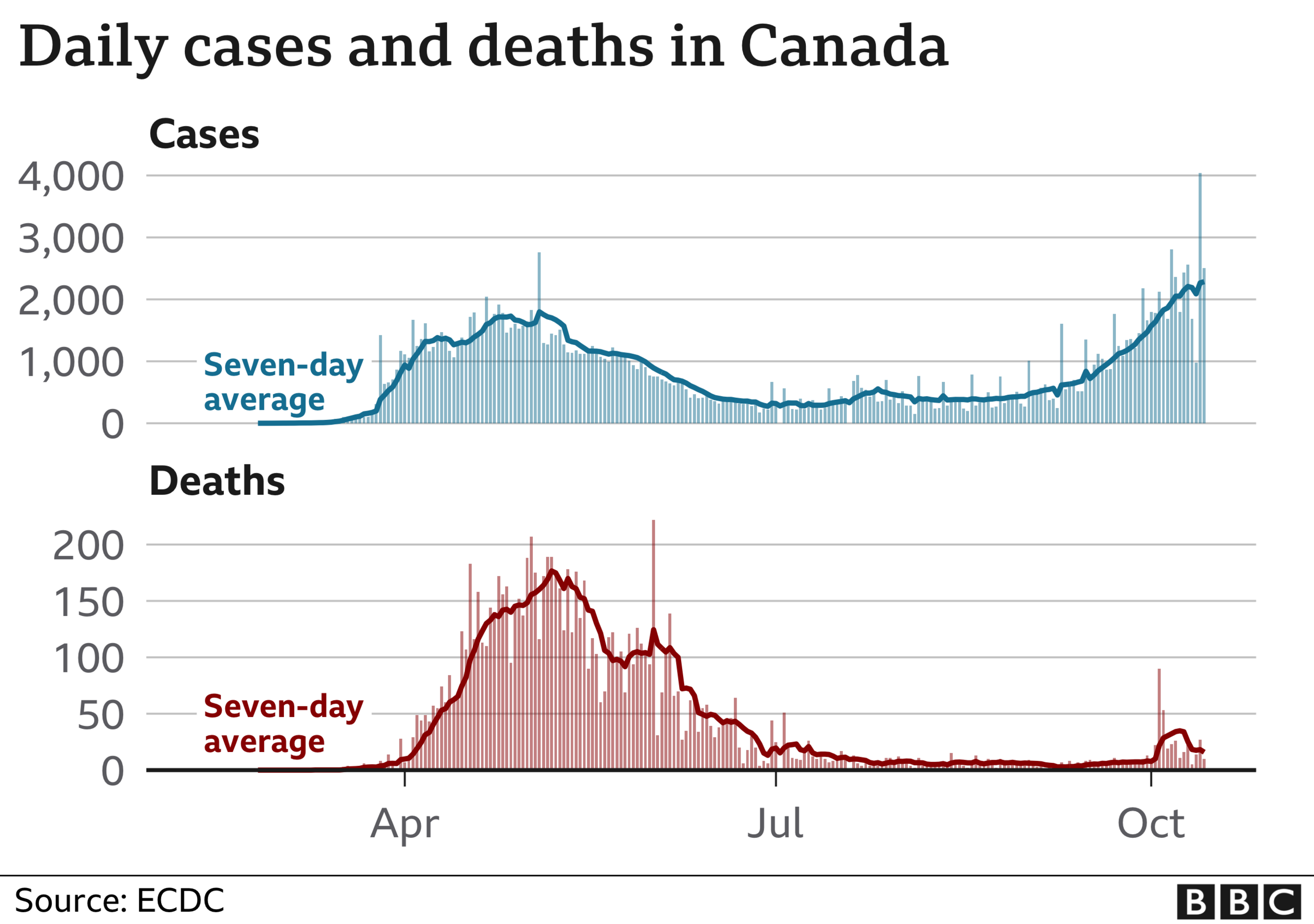

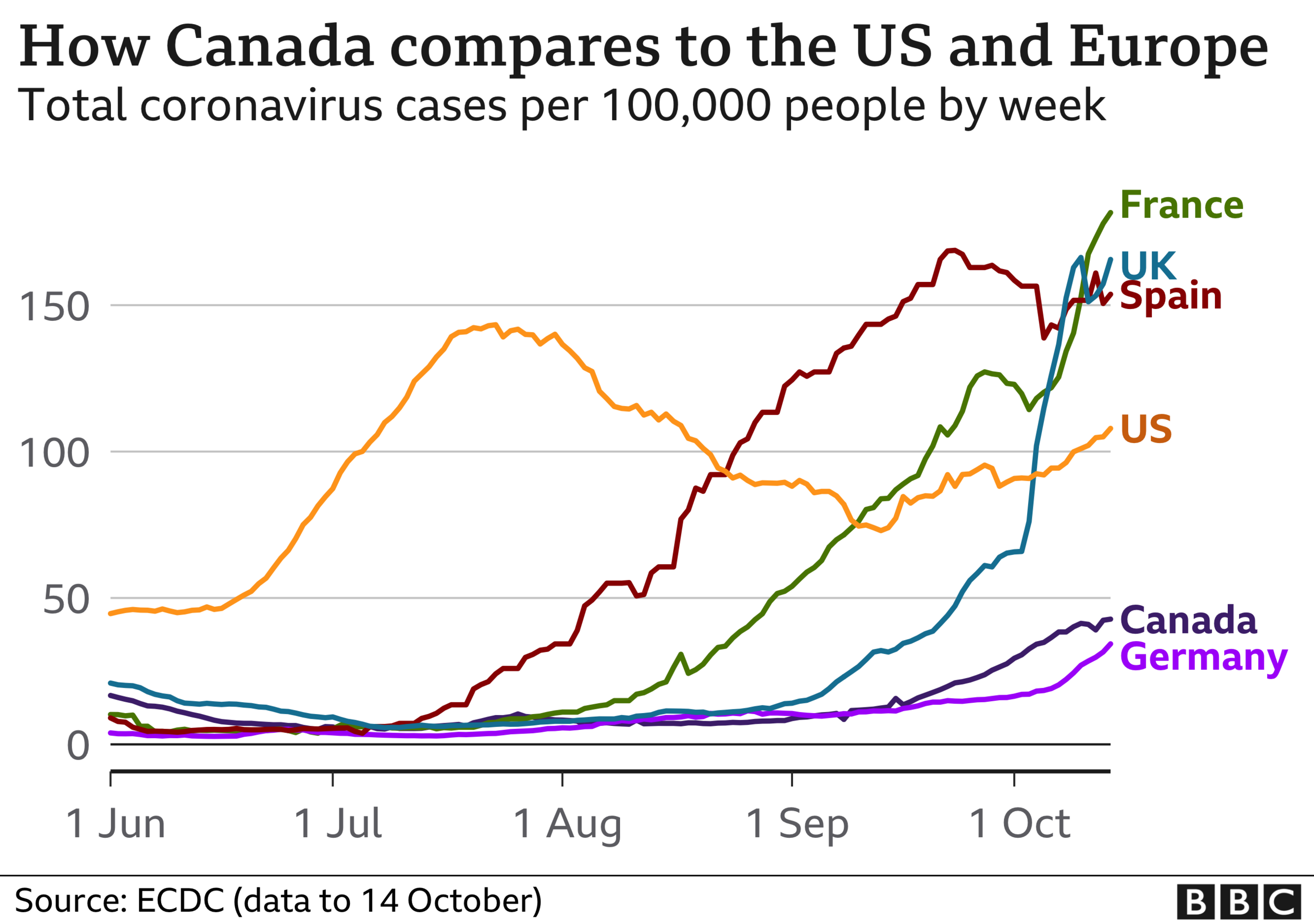

How is the rest of Canada doing?

Canada as a whole managed to stem the tide of the outbreak over the summer months, through full lockdowns in spring to a reopening over the summer.

As of late last week, there had been 191,732 cases nationwide and 9,699 deaths.

But with colder weather approaching, infections have been climbing sharply in many parts of the country, driven by the highly populated provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

Some regions in Canada have brought back restrictions on indoor activities amid a second wave

The average number of people sent to hospital each day is also rising in the places with the most cases, and health officials have warned a major surge still has the potential to overwhelm the healthcare system. Additionally, infections have begun making their way back into long-term care homes.

Parts of Ontario and Quebec have brought back some lockdown measures as they try to bring infections under control, pressing pause on such things as indoor dining and gyms in hotspots like Montreal and Toronto.

Other parts of Canada are fairing better.

Atlantic Canada, the four provinces east of Quebec, has been able to limit community spread and has implemented a travel bubble, with free movement for residents and strict 14-day isolation orders for outside travellers.

The country is still lagging in testing capacity, and has experienced long queues and slow turnarounds for results in some areas as children returned to school.

About 77,000 Canadians are being tested daily, but the goal is to be able to test up to 200,000 daily nationwide.

- Published9 April 2020

- Published28 August 2019

- Published8 March 2019

- Published16 March 2020