New Brunswick outbreak: How a smalltown doctor became a Covid pariah

- Published

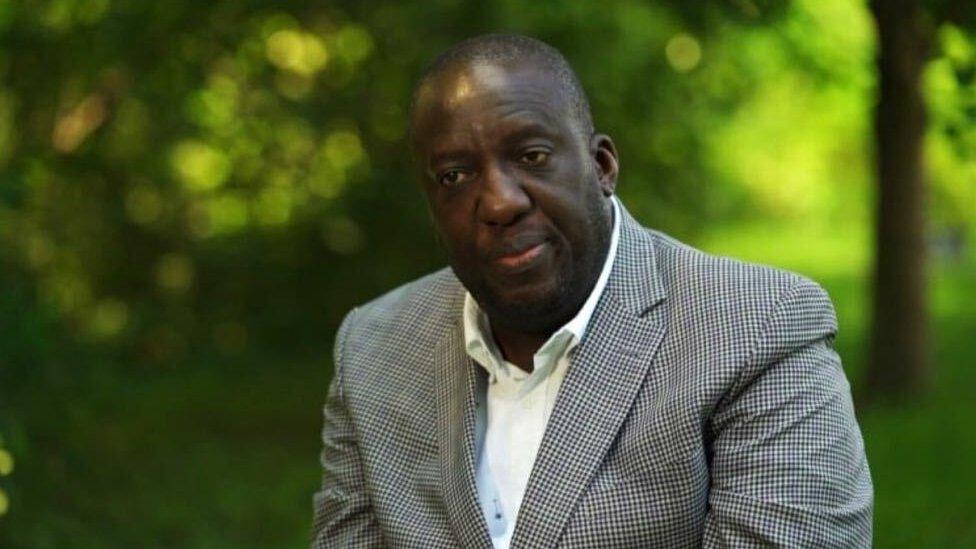

After being labelled the "patient zero" of an outbreak of Covid, a Congolese-Canadian physician says he became a target for racist threats, a pariah in his community, and a "scapegoat" for local officials.

When Dr Jean-Robert Ngola heard that he had to pick up his daughter last May, he quickly did the maths.

His daughter lived in Montreal with her mother, about seven hours away from his home in Campbellton, New Brunswick.

As a family physician, he knew that he needed to be as safe as possible to limit the spread of Covid to others. But as a parent, he had to come get his child so that her mother could attend a family funeral in Africa.

In order to get her and have contact with as few people as possible, he hopped in his car and drove all day, spending the night at his brother's before driving her back.

Before leaving, Dr Ngola called the local police, asking for clarity around the laws about self-isolation.

New Brunswick has one of the strictest quarantine policies in Canada. Along with several other eastern provinces, it has formed an "Atlantic bubble" - in the early months of the pandemic, most forms of travel into the bubble were restricted, and anyone entering had to quarantine for 14 days.

But as a frontline worker, he says police told him he was exempt.

Not wanting to leave his patients without a doctor, he decided to go back to work.

On 25 May, Dr Ngola heard that one of his patients had been diagnosed with the virus. He got tested, and began to self-isolate with his four-year-old daughter.

At 11am on 27 May, he learned he, too, had the virus, although he had no symptoms.

Then, his life began to fall apart. Within the hour, his identity began to spread online. Later in the afternoon, Premier Blaine Higgs, who leads the provincial government, was chastising him on live television.

At least two other people had contracted coronavirus "due to the actions of one irresponsible individual," Mr Higgs said, after nearly two weeks without a single case.

Although the premier did not name Dr Ngola directly, by that time, people had connected the dots, and photographs of his office were circulating online.

Provincial health officials told the media Dr Ngola had contracted the disease in the neighbouring province of Quebec, and spread it to others because he did not follow the 14-day mandatory quarantine for people who had been out of New Brunswick.

But Dr Ngola, and his lawyer Joel Etienne, say the rules were not clear, and Dr Ngola was following the same practices as people around him.

They also dispute the province's claim that he was "patient zero".

Although no criminal charges were filed, Dr Ngola faces a civil charge for violating the Emergency Measures Act and could face a fine up to C$10,200 ($7,600, £6,000). The case is currently making its way before the courts.

His employer, Vitalité Health Network, immediately suspended him without pay for breaking protocols.

"I was the scapegoat. As soon as my diagnosis is made… one hour later, my life changed," he said.

In a statement to the BBC, a spokesperson for Vitalite confirmed that Dr Ngola's suspension continues, and declined to comment further.

The premier's office did not respond to the BBC's request for comment.

The reaction from the community was swift and brutal. Dr Ngola, who is originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, said people were telling him to "go back to Africa" and other forms of racist abuse.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

TEENAGE RITUALS: Growing up, interrupted

SUPERSPREADERS: What makes some events so risky?

Quarantining in his home with his small daughter, he feared for his safety when his address was leaked online and had to go under police protection. But he was also constantly under police scrutiny, he says, because people kept phoning in with bogus "tips" claiming to have seen him break quarantine.

Dr Ngola says the harassment was so bad, he had to leave the province. He was offered a job in a small community in Quebec, where he has been living for the past several months. He says he feels welcome there, but his experience in Campbellton has left psychological scars.

"I cannot have the same life because now I'm public," he says.

This is not the first time he's had to start over. Born in the Congo, Dr Ngola had wanted to be a doctor since he was a small child, after coming down with polio and being unable to get the appropriate medical treatment because it was too costly.

"My childhood ambition was to become a doctor in order that children like myself would be spared," he says.

He paid his way through school by tutoring other students, and practised medicine during his country's brutal civil war.

In 2000, he immigrated to Belgium, where he had to retrain in order to continue to be a doctor. Then five years later, he relocated to Canada, because he felt he would face less prejudice as an African immigrant. Once again, he went back to school in order to practise medicine.

Now, he feels disillusioned. Dr Ngola says he believes his race and immigration status played a factor in how he was treated not only by the public at large, but by the province's top officials.

"What is the difference with me? The difference is I'm black and I'm a foreigner," Dr Ngola said.

Although he felt like a pariah at home, around the country his fellow physicians were rallying to his defence. In September, 1,500 physicians signed a letter condemning his treatment, and demanding an investigation into how his name was leaked to the press.

"All of us signed below have felt tremendous anger, discomfort and frustration with the backlash that followed once you were publicly identified. What unravelled thereafter was unjust, unkind and dehumanizing," the letter, which was spearheaded by Dr Danusha Foster, read.

"We strongly believe that systemic racism coupled with the stigma surrounding individuals infected with the Covid-19 virus have significantly contributed to the crucifixion of your character within the public eye."

Dr Foster, a family physician who lives in Ontario, says that when she first heard about Dr Ngola, she, like many others, judged him.

"We're in a deadly pandemic, and health professionals should be held to a higher standard at this time, because we're supposed to be modelling for the general population what we should be doing," she told the BBC.

Dr Denusha Foster

But after hearing about the abuse he was suffering, and reading media articles critical of the province's investigation, she began to feel sympathy.

"He was being judged in the public eye before the facts were known," she says.

She says patient confidentiality is the "core" of the doctor-patient relationship, and whoever leaked his name should be held to account.

After talking about his case on online physicians groups, she decided to organise the letter of support, to show Dr Ngola that he wasn't alone.

"I hadn't even written my letter, and I already had 800 names that wanted to sign," she says. "We realised as we watched this case that what happened to Dr Ngola, could have happened to anyone of us... if we made one little mistake."

Did he break the rules?

Over 40 cases and two deaths have been connected to the outbreak in the Campbellton region since 27 May. But it remains unclear if Mr Ngola was the source.

Anyone entering New Brunswick from another province outside the Atlantic Bubble is supposed to quarantine for 14 days.

But residents of Campbellton, which is on the border of Quebec, were allowed to cross the border without self-isolating for certain reasons, such as if they worked in Quebec, had to attend a medical appointment in Quebec or if they shared custody of a child in Quebec.

According to the provincial guidelines, external, "all such workers and individuals who are exempt from self-isolation must travel directly to and from work and/or their accommodations, self-monitor and avoid contact with vulnerable individuals"

Dr Ngola spent about 30 hours in Quebec, including an overnight stay with his brother to rest up after the seven-hour drive. He also saw two colleagues in Trois-Rivieres, although they were masked and socially distanced. He also had contact with a petrol-station employee.

Dr Ngola said many of his co-workers went back and forth to Quebec and did not fully self-isolate, so he did not think he was breaking the rules.

His employer, Vitalite Health, told the CBC's Fifth Estate that all workers were ordered to self-isolate after returning to the province unless they lived in Quebec.

Mr Etienne says regardless of whether his client broke the rules, the province failed to do its due diligence before blaming him for the outbreak.

He says they had not finished contact-tracing the four individuals in Quebec whom Dr Ngola had contact with, before claiming the doctor was the source of the Covid cluster in New Brunswick. He says their own private investigator found that neither his brother, the two colleagues, nor the gas station employee tested positive for Covid.

His daughter, however, did. Both she and her father have made a full recovery.

There had been at least one confirmed case of Covid in Campbellton in the days prior to Dr Ngola's diagnosis, and his lawyer says he could have got it from community spread.

- Published17 November 2020