Obituary: Donald Rumsfeld

- Published

Donald Rumsfeld, who served as secretary of defence for President Gerald Ford and President George W Bush, has died aged 88.

Best known for overseeing the US response to the 9/11 terror attacks, his political career eventually came undone by the spiralling conflict in Iraq.

Across a career spanning decades, Rumsfeld forged a reputation as the ultimate Washington insider and a true political survivor notorious for outmanoeuvring his foes. But to his critics he was hawkish and ruthless - a Machiavellian figure and an architect of war.

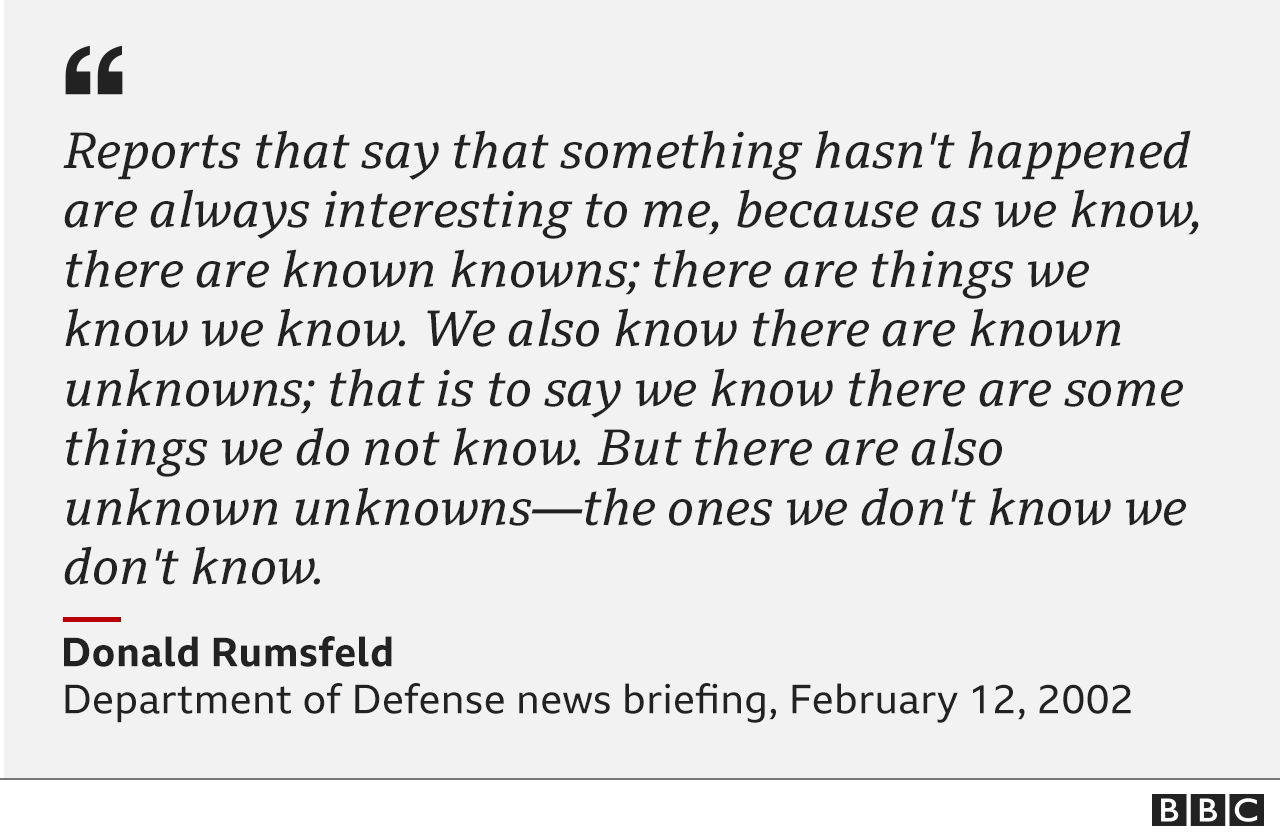

One of his most memorable moments came at a 2002 news briefing when - asked about the lack of evidence linking Saddam Hussein to weapons of mass destruction - he gave a meandering answer about the concept of "known knowns" and "known unknowns" to much public mockery.

Donald Henry Rumsfeld was born in Chicago on 9 July 1932. His father, a real estate salesman, was enlisted in the Navy during WW2. In childhood, Rumsfeld was an Eagle Scout who went on to find a love of wrestling.

After studying political science at Princeton University on a naval scholarship, he followed in his father's footsteps to enlist and served as an aviator and flight instructor between 1954 and 1957.

After transferring to the reserves, he came to Washington DC first as an assistant to a congressman before being elected himself to the US House of Representatives for Illinois in 1962.

Rumsfeld resigned his post in 1969 to direct Richard Nixon's Office of Economic Opportunity, before serving in several other positions in the administration including as US ambassador to Nato from 1973-74.

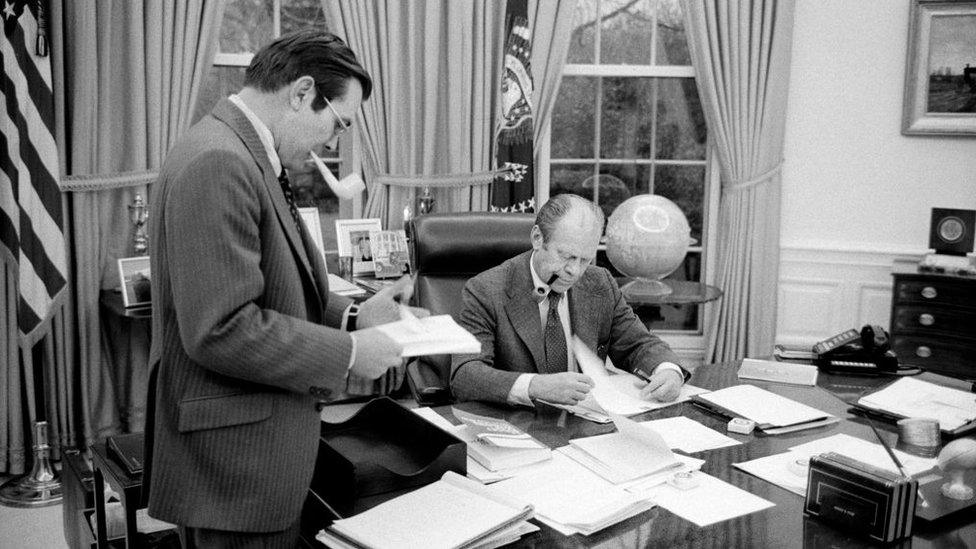

After Nixon's resignation over the Watergate scandal, Rumsfeld was named first as Gerald Ford's transition chairman then as his chief of staff.

Rumsfeld (left) worked under Ford (right) after establishing himself within the Nixon administration

He was then appointed Secretary of Defence in a 1975 cabinet reshuffle and, aged 43, became the youngest to hold the post.

Serving at a time when US policy was still dominated by Cold War anxiety, Rumsfeld oversaw the development of the Trident nuclear submarine and "peacekeeper" MX intercontinental ballistic missile programmes. He also famously undermined Henry Kissinger's work on Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) with the Soviets during this time.

After Ford lost out to Jimmy Carter and left office in 1977, Rumsfeld moved into the private sector while maintaining some part-time federal commitments and roles on the side - including, at one point, serving as special envoy to the Middle East for President Ronald Reagan.

He spent almost a decade in senior management of pharmaceutical firm GD Searle & Co and served as CEO and chairman at electronics manufacturer General Instrument before returning to pharmaceuticals as chairman of Gilead Sciences.

Rumsfeld, seen on the right beside future Vice-President Dick Cheney in 1975, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977

Never far away from politics, he was chosen to head up a bipartisan commission to assess the ballistic missile threat to the United States in 1998. The probe was ignited by sharp criticism of intelligence assessments under the Clinton administration which played down the security risk to continental North America following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The Rumsfeld Report, as the findings came to be known, argued that the US faced a growing threat from overtly or potentially hostile nations including North Korea, Iraq and Iran. It suggested that these states could potentially inflict "major destruction" on the US within five years of deciding to pursue a missile capability - far shorter than the 15 years predicted by intelligence estimates. The findings revived intense debate over the nation's missile defence systems and defence policy.

A return to the cabinet

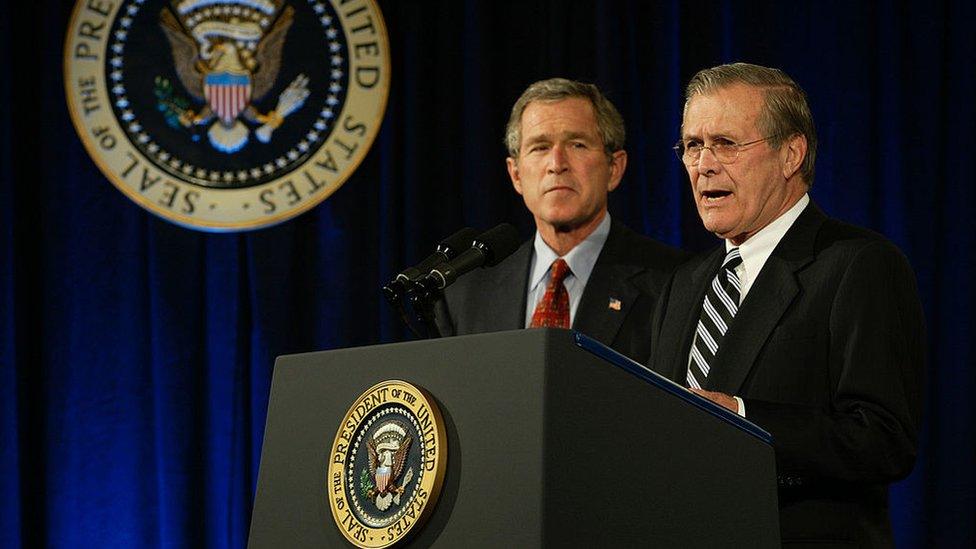

After the knife-edge 2000 election, Rumsfeld was nominated to serve again as defence secretary under George W Bush. Once the youngest to take the post, he became - at the time - the oldest.

A veteran welcomed by party conservatives, Rumsfeld had already served as an adviser to Bush's campaign on foreign policy. Bush described his appointee as a man of "great judgement" with a "strong vision".

George W Bush and Rumsfeld prioritised rebuilding a military they saw as in decline

In the president's cabinet, Rumsfeld found strong personalities in Colin Powell as Secretary of State and Vice-President Dick Cheney - who had succeeded him as Ford's chief of staff back in the 1970s.

A priority for the Bush administration had been readying the Pentagon to deal with new and evolving security threats - with Rumsfeld put in charge of the attempt to revamp and streamline a military seen as resistant to change.

His frank approach to reassert civilian control was widely reported to have offended military top brass in the early days of the administration.

But then, less than nine months into the presidency, the US came under unprecedented attack.

9/11 and aftermath

Rumsfeld had been holding a Pentagon breakfast meeting with congressmen to try and garner support for missile defence when the World Trade Center was targeted on the morning of 11 September 2001.

Insisting on continuing with his daily briefings, Rumsfeld was still inside when the defence headquarters itself was hit with another hijacked aircraft.

He would later recall feeling the building shake and running toward the crash site - leading to a scramble as officials struggled to locate him. "Outside I found fresh air and a chaotic scene," he wrote. "For the first time I could see the clouds of black smoke rising from the west side of the building. I ran along the Pentagon's perimeter, and then saw the flames."

Video footage aired on CNN showed Rumsfeld helping to stretcher someone to safety before going back inside to help co-ordinate the nation's response.

Rumsfeld (centre) seen touring Ground Zero alongside former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani (right) in November 2001

Evidence would later emerge in declassified notes that within hours of the attack, Rumsfeld was already floating the idea of retaliatory strikes on not just Osama Bin Laden - the main suspect - but on Saddam Hussein's Iraq too.

'Known unknowns'

The initial response was to foreshadow what was to come.

On 7 October, less than a month after the attack, US forces began an air campaign against al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

A swift ground campaign followed, improving Rumsfeld's reputation as he provided regular updates at briefings.

But by 2002, the Bush administration's attention had turned to Iraq. The president singled out the country - along with Iran and North Korea - as part of what he dubbed the "axis of evil" whom he said threatened the peace of the world by pursuing weapons of mass destruction.

It was just weeks after that State of the Union address when Rumsfeld was asked about the lack of evidence at a Pentagon briefing and responded with his famous "known and unknowns" retort.

The concept was not invented by Rumsfeld - but the response nonetheless brought widespread ridicule at the time given the controversy over the Bush administration's stance and push for war.

After giving up on getting a resolution authorising the use of force passed at the UN, the US and UK pressed ahead with plans to invade alone. Operation Iraqi Freedom began in March 2003 despite continued questions over their evidence and rationale.

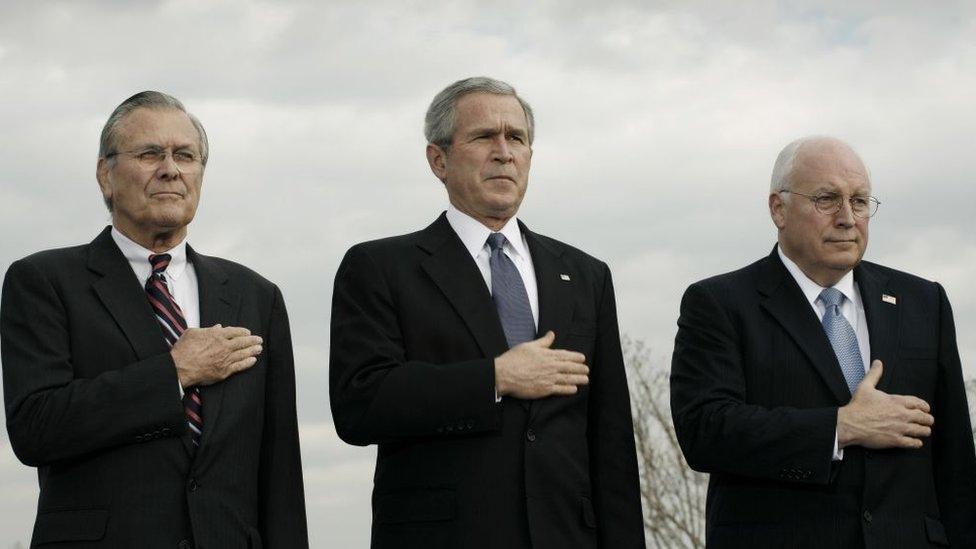

Rumsfeld (left) and Cheney (right) were seen as key players in the hardline Bush Doctrine

Rumsfeld, one of the most hawkish in the cabinet, was seen as a key architect of the conflict.

That year he predicted in a memo the wars would be a "a long, hard slog" - something history proved as painfully true, with US troops still embroiled in exiting the conflicts almost two decades on.

The defence head was never far away from news headlines and blunders. Rumsfeld's time in office was dogged by criticism over his handling of the conflicts and he built a reputation for his candid and controversial off-the-cuff remarks.

But Bush stood resolute by him, even in the wake of the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal - where photographs of US troops posing next to Iraqi prisoners in humiliating poses were leaked.

Bush faced resistance from senior Republicans over his continued loyalty to Rumsfeld

By then it was clear that despite the fear and rhetoric - Iraq had no stockpiles of biological, chemical or nuclear weapons prior to the invasion. And as insurgency and violence spiralled, so did questions over Rumsfeld's leadership and he found himself under mounting pressure to quit.

Rumsfeld said he offered to resign twice over Abu Ghraib, but the president continued to back him and even asked him to stay on in the post after he won re-election in November 2004.

It took two more years, and bruising losses for the Republicans in the 2006 mid-term elections, for Bush to finally acknowledge a "fresh perspective" on the conflict was needed. By this time Rumsfeld had weathered public criticism over equipment from members of the military themselves and even an admission he had used a machine to sign signatures on the condolence letters to the families of dead soldiers.

The president remained complimentary of his outgoing pick's work and legacy. But his own father, George Bush Senior, was not as positive - later describing Rumsfeld as "an arrogant fellow" who he believed had hurt his son's presidency.

In his 2011 memoir, Rumsfeld remained largely defiant over the war's handling - though he did express regret over some of his comments and conceded the US could have sent more troops into Iraq.

In 2013 he was the subject of The Unknown Known - a documentary by Academy Award winning director Errol Morris.

The filmmaker set out to delve inside Rumsfeld's mind like he had with former Secretary of Defence Robert S McNamara in The Fog of War, but later conceded that after 33 hours of interviews with the enigmatic Rumsfeld, he seemed to know even less about the origins of the Iraq war than when he started the project.

He compared meeting Donald Rumsfeld to Alice in Wonderland's perplexing encounter with the Cheshire Cat in the Lewis Carroll classic.

"I was left with the frightening suspicion that the grin might not be hiding anything," he wrote in the New York Times. "It was a grin of supreme self-satisfaction and behind the grin might be nothing at all."