Sandra Day O'Connor: A ranch girl who became 'queen of the court'

- Published

Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor blazed a trail for women in law

"Good in every way, except he's not a woman."

This was the ambivalent reaction of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor to the nomination of her successor to the US Supreme Court.

Such sentiments were typical of O'Connor, the first female justice to sit on the nation's top court.

The expectations of O'Connor's historic appointment in 1981 weighed heavily on her shoulders throughout her 26-year term.

A self-professed "cowgirl from the Arizona desert", the conservative justice had to constantly prove she was better than men and on the side of women.

O'Connor did so with guile, drawing on her political acumen as a Republican activist and state senator to navigate the choppy waters of Supreme Court decisions.

Ideologically, O'Connor was a moderate, a position that often gave her the decisive swing vote in a court sharply divided between conservative and liberal justices.

For much of the 1980s and beyond, O'Connor cast consequential votes on an array of contentious issues, from abortion rights to the disputed presidential election of 2000.

As a standard bearer for gender equality, O'Connor was succeeded by the second female justice to sit on the Supreme Court, the "notorious" Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

O'Connor never had a nickname that stuck, nor a politically charged cult following. Instead, O'Connor made her mark in a way that few justices can.

She held the balance of power on the court for almost two decades, making her one of the most powerful women in the country, notorious in all but name.

"Justice O'Connor was the queen of the court, for a long time," one of her biographers Linda Hirshman told the BBC.

The rancher's daughter

Independent, hard-working and self-sufficient, O'Connor owed many of her defining character traits to her isolated and at times austere upbringing in the country's south-west, where she was born in El Paso, Texas in 1930.

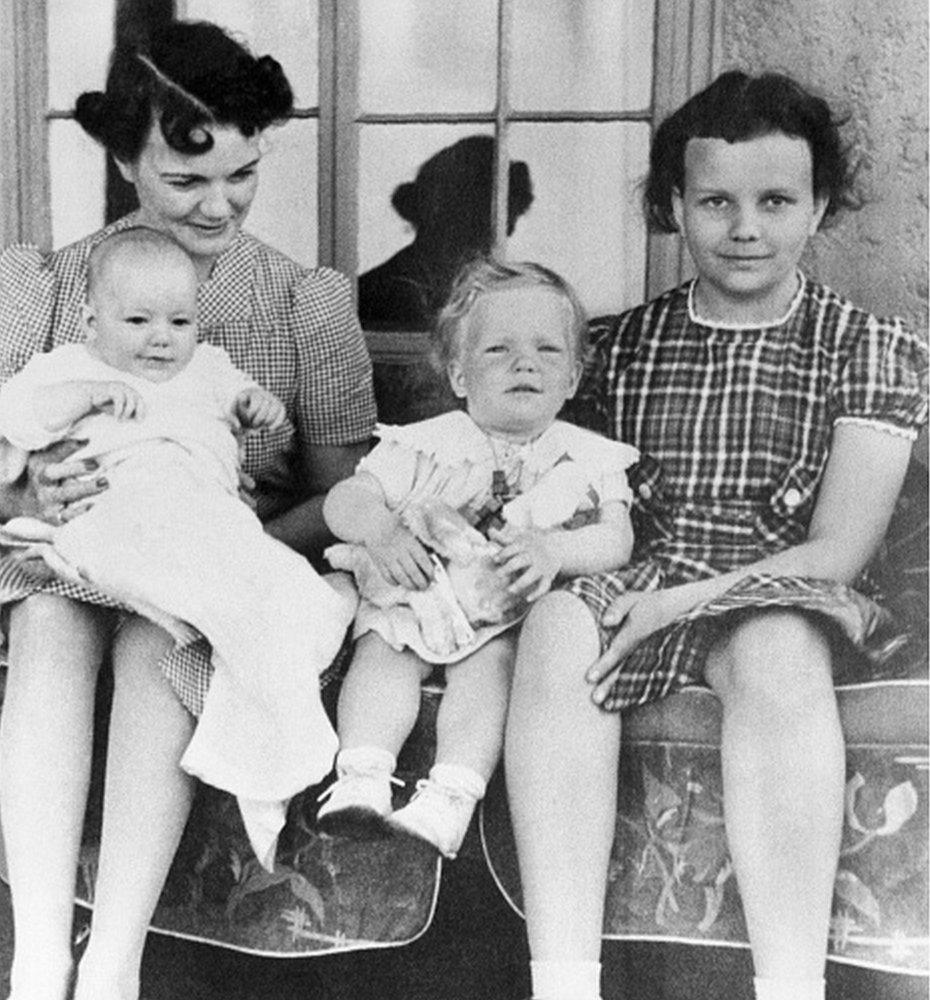

Lazy B, a 198,000-acre cattle ranch in the desert straddling Arizona and New Mexico, was the place she called home. There, in a simple farm house 14km (nine miles) from the nearest paved road, O'Connor was raised by her mum, Ada Mae Day, and dad, Harry Alfred Day.

It was a rugged childhood, shaped by the ups and downs of the family business and the trappings of ranch life. Learning to ride a horse, drive a truck and shoot a .22-calibre rifle with her dad were as much a part of her early education as reading books with her mum.

O'Connor (right) grew up on her family's ranch in Arizona

For her formal education, though, O'Connor was sent to live with her grandmother in El Paso. At 16, she enrolled at Stanford University to pursue the unfulfilled dream of her father, who had yearned to study there before committing to the family ranch.

Her time at Stanford was fruitful, both academically and romantically, earning her two degrees (in economics and law) and the affections of several suitors. One biographer, Evan Thomas, reckons she received four marriage proposals at Stanford. One of them, according to Mr Thomas, came from future Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

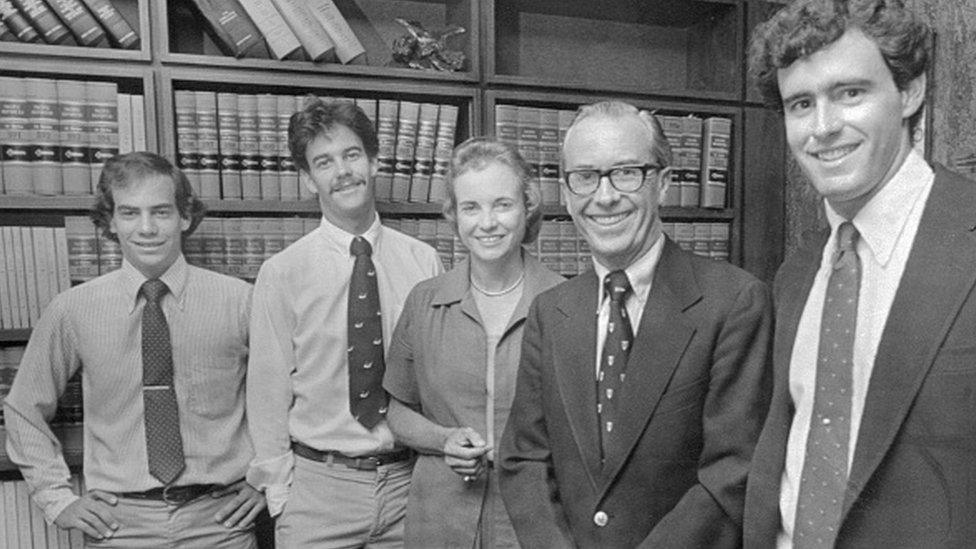

O'Connor (front row, second from the left) studied law at Stanford with Rehnquist (back row, furthest left)

The proposal was rejected. Then entered fellow Stanford law student John Jay O'Connor, who she married in 1952. On paper, their CVs were evenly matched, both editors of the prestigious Stanford Law Review. In reality, there was a yawning gender gap between them.

'Law firms wouldn't hire women'

"No-one gave me a job," O'Connor told the International Bar Association in 2011, external. "It was very frustrating because I had done very well in both undergraduate and law school and my male classmates weren't having any problems."

In her first job, she agreed to work for nothing, with no office, for a county attorney in San Mateo, California. Such conditions would be risible by today's standards, but O'Connor persisted and was eventually able to muster a small salary.

What is the US Supreme Court and why does it matter?

A US army draft took O'Connor and her husband to Germany and, upon their return in 1957, they decided to settle in Maricopa County, Arizona. Even then, sexism impeded O'Connor's desired career path.

"Law firms wouldn't hire women lawyers," O'Connor said at the Aspen Ideas Festival in 2011, external. "So I had to figure out some way to practise law."

She did find a way, setting up her own walk-in legal practice at a shopping centre, where she took on petty cases. It gave her skin in the game, but she soon decided her priorities lay elsewhere: at home with her three sons, Scott, Brian and Jay.

The homemaker turns lawmaker

From the birth of her second son Brian in 1960, O'Connor took a five-year break from the legal profession. This period is often framed as O'Connor's "career hiatus", but Scott said it was nothing of the sort.

"She had more energy than 20 people," Scott told the BBC. "She wasn't just sitting there in her slippers watching soap operas at home."

O'Connor had three sons (pictured left to right) Jay, Brian and Scott

On top of parenting, O'Connor had various side-hustles to keep her busy. She delved into politics for the Maricopa County Young Republicans, public health for Arizona State Hospital and charity for the Salvation Army.

This flurry of volunteer activity raised O'Connor's profile and expanded her connections on the political scene in Arizona. Thereafter, doors started to open.

In 1965, she landed a job as an assistant attorney general for Arizona. In that role, she earned the good graces of Arizona Governor Jack Williams, who appointed her to a vacancy in the state senate.

She won re-election twice, which, to her three boys, was "no big deal" at the time.

"My brothers and I figured that our mum has a different job to the other mums," Scott said. "But we didn't realise how unusual that was back in those days."

On one occasion, O'Connor convinced her fellow senators to pause a legislative session so she could make cookies and lemonade for her sons, external. Clearly, O'Connor commanded respect.

This clout, underpinned by her hobnobbing and won't-take-no-for-an-answer attitude, helped her break down the gender barriers in her path. Her first glass-ceiling breach came in 1973, when she was elected majority leader of Arizona's Senate. It was a landmark first for a woman in the US.

A year later, she switched gears from politics to law, winning election as a county judge in 1975 before her appointment to the Arizona Court of Appeals in 1979. Her rise was timely.

The president picks 'a woman for all seasons'

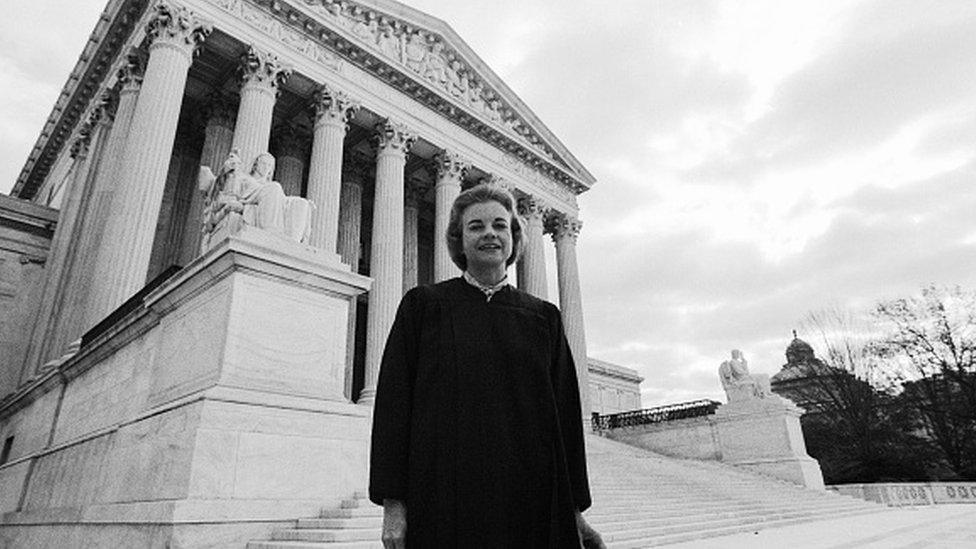

Running for president in 1980, Ronald Reagan pledged to appoint the first woman to the Supreme Court. So when Reagan won the election, O'Connor, the ranch girl cum lawyer cum politician cum judge, was well placed to fill the next vacancy on the court.

President Reagan called O'Connor a "woman for all seasons"

O'Connor had supporters in high places, not least her old flame Justice Rehnquist, who pressed for her selection behind the scenes, external.

A 15-minute interview with O'Connor at the White House was all it took for President Reagan to make up his mind. Charmed by her south-western disposition and impressed by her sharp intellect, Reagan named O'Connor - a "woman for all seasons" - his nominee in 1981.

Scott said his mum's nomination "was like being struck by lightning".

"It was hard to believe," he said. His mum was taken aback too. "I had never been a law clerk there, I had never tried a case at court," O'Connor told the International Bar Association.

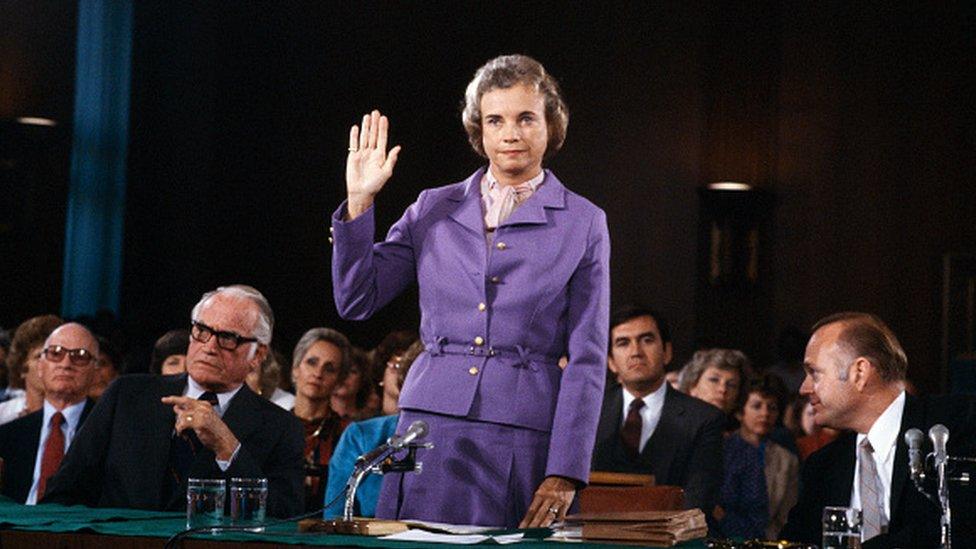

Given the outcome of her Senate hearings - the first to be broadcast live on TV - she needn't have worried. Her nomination was largely well received by liberals and conservatives alike. The emphatic result of her confirmation vote, 99-0, reflected this.

O'Connor's nomination was supported by liberals and conservatives

O'Connor represented "a kind of bipartisan consensus about the American experiment and how we should govern ourselves", Hirshman, author of Sisters in Law, said.

"She came from Arizona, where… there was a lot of old-fashioned American consensus. Her confirmation hearings were a love fest."

With O'Connor's nomination confirmed, "the brethren" lost their 191-year monopoly on the Supreme Court. A new dawn had broken.

A consensus-builder with an unpredictable streak

As a symbol of progress for women, O'Connor made her presence felt. When it came to the law, however, O'Connor did not bring her ideology to bear on the court. In fact, those who worked with her question whether she had an ideology at all.

"She was one of a set of justices who was pragmatic," Eugene Volokh, a legal scholar who clerked for Day O'Connor in 1993, told the BBC. "Her view was: you want the legal system to work effectively, and you want to interpret statutes and constitutional provisions with an eye towards that. The result, in some situations, was that she wasn't very predictable."

O'Connor has been described as a moderate and a consensus-builder

Her son Scott saw her as an "incrementalist" who "wasn't trying to knock down tradition too much". In general, O'Connor refrained from making sweeping judgments and was mindful of the rights of individuals and states.

In her early years on the court, O'Connor was a core member of the conservative bloc. Only when the court shifted rightwards, following the appointments of conservative justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, David Souter and Clarence Thomas, did O'Connor start to break ranks more frequently.

She had a tendency to side with liberal justices on matters of equality and civil rights. Yet, the record shows she still sat with the conservative bloc more than the liberal one in contentious 5-4 decisions.

One notable schism between O'Connor and the conservatives came in 1992 with Planned Parenthood v Casey, a controversial case about abortion rights. O'Connor joined a 5-4 majority in affirming Roe v Wade, the 1973 decision that decriminalised abortion in the US.

The abortion battle explained in three minutes

The vote confounded critics of O'Connor, who had previously expressed her personal abhorrence of abortion, external. But while Roe v Wade was saved, a new test was applied to the restriction of abortions at state level. States were given more latitude to impose regulations unless they "unduly burdened" women seeking abortion.

"Many people in the abortion rights movement believe we would have been better off if they had outright overruled Roe v Wade," Hirshman said. "We could have had a referendum on whether Americans really wanted to go back to women getting back-alley abortions."

In 2022, her eventual replacement - hardcore conservative Justice Samuel Alito - authored the majority opinion that finally overturned Roe v Wade.

A tainted legacy

O'Connor's most contentious decision of all, perhaps, was that of Bush v Gore in 2000.

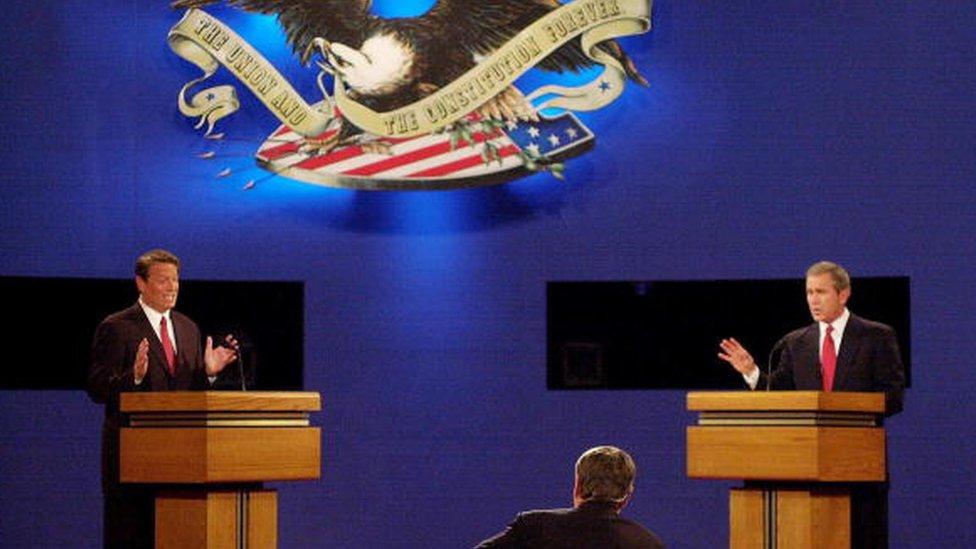

That year, Republican George W Bush and Democrat Al Gore fought a closely contested election for the presidency. The result was so close in Florida, state law required a recount. Legal battles over the recount ensued, leading to a controversial decision by the Supreme Court.

O'Connor voted with the 5-4 majority to halt any legal challenges to the results of the election, effectively putting Bush in the White House.

Bush v Gore was one of the most controversial decisions the Supreme Court has made in modern times

The decision was seen as a Republican stitch up because O'Connor was reported to have been upset at the prospect of a Gore win on election night, external. She denied this, but Democrats were incensed, accusing O'Connor of political bias.

Her legacy, Hirshman said, will forever be tainted by that ruling.

It was one that came back to haunt O'Connor following her retirement from the court in 2006. Bush locked in a conservative-leaning court, which ultimately dismantled some of her biggest compromise achievements on abortion rights and campaign finance.

This bitterly disappointed O'Connor but, as she said in 2011, "life goes on".

A second career, tinged with sadness

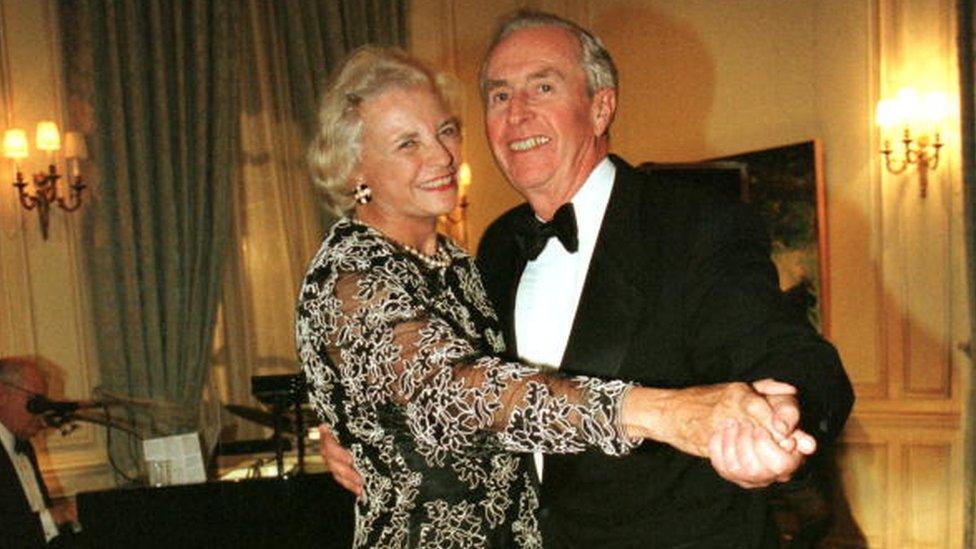

And so it did for O'Connor. At 75, she took a relatively early retirement for a Supreme Court justice. She did so to care for her husband, who died in 2009 after living with Alzheimer's disease for many years.

O'Connor was devastated, but later told biographer Mr Thomas that retiring from the court was "the biggest mistake, the dumbest thing I ever did", external. Nevertheless, O'Connor threw herself into a "second career".

O'Connor's husband died in 2009 after living with Alzheimer's for years

"After leaving the court, in her 80s, she took on a project to educate young Americans about civics," Scott said. One initiative, iCivics, uses gaming technology to teach six million students a year about how the US government works.

"All Supreme Court justices now talk about the importance of civics. It was mum who got that going," Scott said.

O'Connor remained active in public life well into her 80s, until she finally encountered an obstacle she couldn't overcome.

"Some time ago, doctors diagnosed me with the beginning stages of dementia, probably Alzheimer's disease," O'Connor announced in 2018.

O'Connor's elevation to the court represented a triumph for the progression of women in law

"While the final chapter of my life with dementia may be trying, nothing has diminished my gratitude and deep appreciation for the countless blessings in my life.

"As a young cowgirl from the Arizona desert, I never could have imagined that one day I would become the first woman justice on the US Supreme Court."

'Here lies a good judge'

History remembers firsts, regardless of their legacy. O'Connor left a legacy that transcends her first, not least in the progression of gender equality, constitutional law and civic education. Simple intentions, her brother said, were at the root of it all.

"She didn't do it for legacy, she didn't do it for heroism," Alan Day told The Arizona Republic newspaper, external. "She was who she was because she wanted to be a good person and do good things."

Indeed, at her confirmation hearings in 1981, O'Connor was asked what kind of legacy she'd like to leave.

"Ah, the tombstone question," she said. "I hope it says, 'Here lies a good judge.'"

Related topics

- Published23 October 2018

- Published3 June 2019

- Published31 October 2018