Can $15bn in Covid relief funds help arts venues survive?

- Published

Wichita's Wave, which opened in 2018, has been shuttered since March

Arts and music venues across the US have been hard hit by the pandemic. Can $15bn in new relief funds help them survive?

"It's heart-breaking and it's terrifying," says Adam Hartke, who co-owns two music venues in Wichita, Kansas, that have been closed since the first wave of pandemic lockdowns in March.

"We're out of business. We've done nothing. There was a point where we were thinking of not ever reopening," says Paul Rizzo, the owner of The Bitter End in New York City's Greenwich Village, which has been shut for the past nine months and would be extinct if not for an understanding reached with the landlords.

Independent arts venues across the US - comedy clubs, dance halls, theatres and other performance arts spaces - say that they have been hit especially hard by the economic upheaval caused by the coronavirus pandemic and are at risk of permanently lowering their final curtains.

"There's no business to be had if you can't have people in the room, and your entire job is to have people in the room," says music promoter Rev Moose.

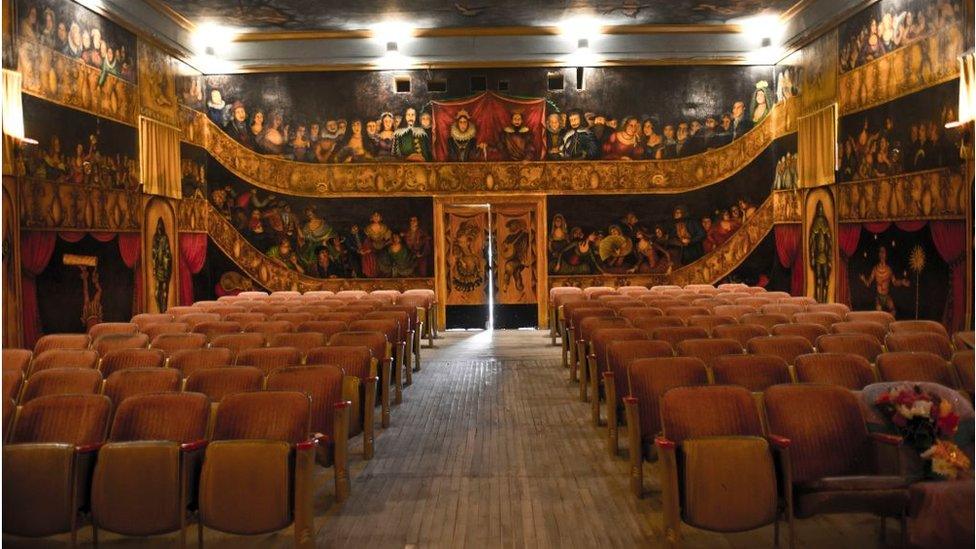

An empty theatre in Death Valley, California

Mr Moose co-founded the National Independent Venue Association (Niva), as it became clear in March that places that bring together crowds would be closed for a while.

To lose these arts venues would devastate music culture and local economies, say the over 3,000 club owners, producers, stage managers, promoters and talent agents who have joined Niva since Mr Moose first began hosting conference calls with members of the independent US music scene.

Unlike other business sectors that have been hit hard by the coronavirus, performance centres are in a uniquely challenged position due to thin profit margins that rely on large audiences.

Restaurants, shops, hotels - all in struggling industries - have been able to re-open at reduced capacities in some form, but most small concert halls and theatres have remained shuttered throughout the entire pandemic.

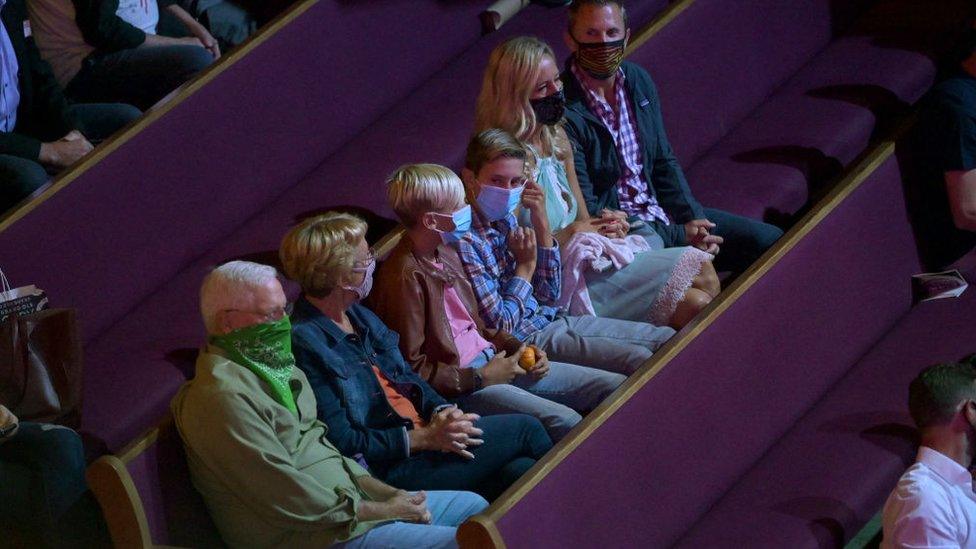

A small number of larger venues, like the nearly century-old Grand Ol Opry, which bills itself as the home of country music in Nashville, Tennessee (aka "Music City") have begun re-admitting small audiences under the supervision of public health officials.

Nashville's Grand Ol Opry reopened in October for its 95th anniversary

Fans of country music at the Grand Ol Opry

But the vast majority remain closed to viewers as they hold online and outdoor performances in an effort to raise a small percentage of their usual revenue. Hundreds of locations, according to Mr Moose, including the Lizard Lounge in Dallas and Great Scott in Boston, have already announced their permanent closure.

Major cultural institutions such as The Bitter End, San Francisco's Boom Boom Room and LA's Comedy Store have turned to online crowd-funding to help the clubs hold on until they can continue packing houses once again.

But most venues in the US have seen revenue collapse by over 90% according to Niva, and have been forced to furlough or lay off all of their employees. Until they are able to reopen at 100% occupancy, they will not be able to even come close to breaking even, let alone turn a profit.

Lady Gaga, on the roof, is among many musicians who got their start at The Bitter End

"No business is set up to run like that," says Mr Moose, whose boutique music marketing company Marauder imported the Independent Venue Week concept - a week celebrating indie venues - to the US from the UK.

"You can't do it. You couldn't do it with a lemonade stand. You certainly can't do it with a brick and mortar building."

Venues that have partially re-opened at 10% or 20% capacity, he says, still have 100% of their normal operating costs, including steep insurance and downtown rental fees.

"Most of the venues that have tried this have found they lose less money closed than they do open," he says.

Under the leadership of Dayna Frank, the owner of First Avenue in Minneapolis (which helped launch the careers of musicians Prince and Lizzo), the club owners began hiring Washington lobbyists and organising venues in all 50 states to begin petitioning their lawmakers for relief funds.

There is now a lifeline.

Over the summer Democratic and Republican lawmakers introduced the Save Our Stages Act.

It later came to be attached to the $900bn (£660bn) coronavirus relief stimulus bill passed by both houses of Congress and signed by the president in late December, despite Mr Trump's opposition to included funding for museums and a theatre in Washington DC.

The Save our Stages Act pledges $15bn in government loans to venues that have lost at least 25% of their business, with highest priority given to locations that have lost at least 90% of their revenue. Venues must have under 500 employees and cannot be publicly traded companies. Museums are also included as long as they have theatres or auditoriums for performances.

It has attracted the support of over 600 musicians and performers, from Billie Eilish to David Letterman to Lady Gaga.

The Foo Fighters' Dave Grohl on Monday issued a "huge, heartfelt thank you" to the act's supporters. saying preserving independent venues "gives the next generation of young musicians a place to cut their teeth, hone their craft, and grow into the voices of tomorrow".

Broadway actor and musician David Lutken was only one week away from debuting "Hootenany: the Musicale," created by him and his theatre director wife, when the pandemic abruptly ended that plan.

He's been lucky enough to pick up a few gigs, performing online or outdoors "playing in painted circles on the grass". But he says that the other roles in showbiz - besides actor and performer - have been hit especially hard.

Broadway performances have all been cancelled

"A big part of what Covid has shut down is all of the things behind the scenes," he says referring to everyone besides the performers, who "build the whole show".

"We had all kinds of props and costumes and everything to go along with this music and now it's just sitting in the storehouse in Milwaukee waiting to be used."

Mr Lutken says it's only fair that performers get help from the government. "Giving people money," he says, is something the "government needs to do it every once in a while for everyone, no matter what you do. No matter if you're a plumber or whatever, in a situation like this".

'Please don't let the music die'

Most of those involved in Niva were previously unknown to each other, as there had never before been a national advocacy group dedicated to their cause until the pandemic hit.

"Nobody knew who we were. Nobody needed to know who we were," says Mr Moose. "Prior to this whatever problems came our way we just figured out. We've never had to go to Congress and say 'help'."

Paul Rizzo's famed venue The Bitter End began as a coffee shop in the 1960s back when folk star Bob Dylan used to wander in to perform, and has more recently fostered the rise of superstar Lady Gaga. Mr Rizzo has watched as other bars and clubs have folded up and down New York's Bleecker Street.

"It's been devastating," says Mr Rizzo, 56, who has worked at the 230-person capacity club since 1992. He considers his business "one of the lucky ones" since his landlords have been understanding as to why he can't pay the roughly $23,000 monthly rent.

Paul Rizzo's club has been around since the 1960s

The property company has owned the building since before he arrived, he says, and is large enough to weather the loss in rent. Some smaller and less established landlords have been forced to evict other nearby venue owners.

"You know when I talked to people [in Niva] about this in the beginning we didn't have a vaccine, we didn't have therapeutics, New York City was getting hit hard," he says.

But he predicts that it will still be a long time before audiences - and tourists - feel comfortable returning to New York City's famed night scene.

Mr Rizzo says there won't be a "war-is-over moment", no single day "where everyone just all of a sudden starts feeling safe and takes masks off and stops distancing and runs around naked like at Woodstock".

"It'll be a gradual thing," he says, as people begin leaving their homes with cravings for live, in-person, entertainment.

Related topics

- Published22 December 2020

- Published9 October 2020