Trump's Christian supporters and the march on the Capitol

- Published

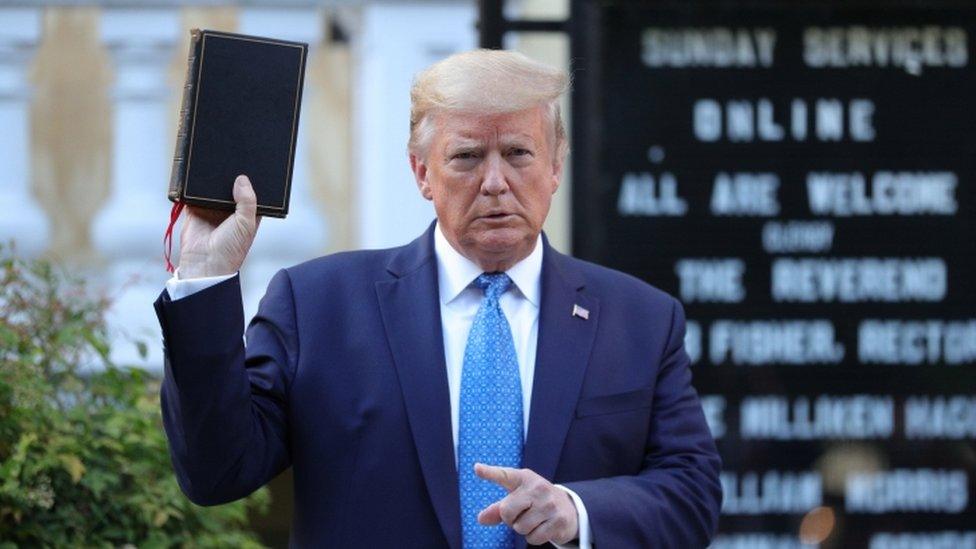

Christian supporters of President Donald Trump were among the thousands who descended on Washington DC last week. Their presence highlights a divide in American Christianity.

Before the march on the US Capitol began last Wednesday, some knelt to pray.

Thousands had come to the seat of power for a "Save America" rally organised to challenge the election result. Mr Trump addressed the crowd near the White House, calling on them to march on Congress where politicians were gathered to certify President-elect Joe Biden's win.

The crowd was littered with religious imagery. "Jesus 2020" campaign flags flapped in the wind alongside Trump banners and the stars and stripes of the US flag.

The throng did march to Congress, a protest that led to chaos at the Capitol.

At least one group carried a large wooden cross. Another blew shofars - a Jewish ritual horn some Christian evangelicals have co-opted as a battle cry. Elsewhere a white flag featured an ichthys - or "Jesus fish" - an ancient symbol of Christianity.

For some Christians, seeing religious symbols alongside Confederate flags was shocking.

But for others, Mr Trump is their saviour - someone who was "defending Christians from secularists" as Franklin Graham, son of the late evangelist Billy Graham, told the BBC.

The day before the rally, a throng of fervent religious supporters of President Trump held a "Jericho March" in Washington. Brandishing crosses and singing Christian hymns, they marched around the Capitol re-enacting the biblical story of when the Israelites besieged the enemy city of Jericho.

The imagery on display was revealing of not just the racial and political divides in America, but the religious divides as well.

Exit polls suggest that in 2020, like in 2016, around four-fifths of white evangelicals - who make up a quarter of the American electorate - backed the Republican president.

But the opposite is true of black Christians - around 90% intended to vote for Democrat Joe Biden, according to pre-election polling.

Ever since white evangelicals became a political force in the late 1970s, they have campaigned against access to abortions, sought to bolster religious liberty laws, and encouraged support for the state of Israel.

In all these areas the Trump administration has delivered: limiting government funds for groups supporting abortions, appointing more than 200 conservative judges to federal courts and three to the US Supreme Court, and moving the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem - a long held desire among some white evangelicals.

They admit Mr Trump has flaws. In the words of one of his most loyal supporters, Texas megachurch leader Robert Jeffress, the president is "no altar boy".

"He doesn't pretend to be overly pious," Mr Jeffress told me before the election.

"But that's not why evangelicals turned out for him. It wasn't for his personal piety. It was for his public policies."

'Christian nationalism' in the US

But aside from specific campaign issues, some academics say "Christian nationalism" was behind much of the religious support for Mr Trump's campaign.

They say Christian nationalism merges Christian identity with national identity: to be American is to be Christian. Proponents believe that America's success depends on its adherence to conservative Christian positions and warn, in Mr Trump's words, of "an assault on Christianity" from political opponents.

"Voting for Trump was, at least for many Americans, a symbolic defence of the United States' perceived Christian heritage," the sociologist Andrew Whitehead wrote in a paper analysing the support for the president.

Academics such as Mr Whitehead and Philip Gorski, professor of sociology at Yale University, argue that throughout his presidency, Mr Trump explicitly played to Christian nationalist ideas by repeating the claim that the United States is abdicating its Christian heritage.

A Trump supporter prays in front of Capitol building

He promised "to protect Christianity" and for many supporters his campaign slogan "Make America Great Again" could have been synonymous with "Make America Christian Again".

At a rally in Ohio last year he warned a Biden presidency would mean "no religion, no anything".

"Hurt the Bible, hurt God. He's against God, he's against guns," he claimed.

But American Christianity is divided.

The Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church of the US, the Most Reverend Michael Curry, described the riots as a "coup attempt" and "deeply disturbing".

The Episcopal Bishop of Washington, the Right Reverend Mariann Budde, said the religious symbols on display were "the most heretical, blasphemous forms of Christianity".

"This has been part of our nativist, racist Christian past from the beginning," she told the Sunday programme on BBC Radio 4. "What has been different in the Trump presidency has been the legitimisation of it."

Next week, Mr Biden will be inaugurated as only the second US President who is openly Catholic.

The battle for the Christian vote in the US election

In many ways he was a more suitable candidate for Christian voters than Mr Trump.

He attends Mass at least once a week, his speeches are infused with biblical language, and he goes out of his way to describe the role faith has on his politics.

But many Christians, including some of Mr Biden's fellow Catholics, refuse to see him as a "real" Christian because of his support for abortion access and for LGBT rights.

Quoting the biblical book of Ecclesiastes in his victory speech after the November election, Mr Biden said it was "a time to heal" in America.

So can Mr Biden persuade some of Trump-supporting Christians that - in his words - he will "restore the soul of America"?

There is little evidence in the reactions of many evangelical leaders to last week's riots that they are abandoning Mr Trump.

Some, like the prominent evangelical writer and radio host Eric Metaxas, have promoted false conspiracy theories that it was the loose-knit left-wing antifa activists masquerading as Trump supporters who led the riot.

Others, like Franklin Graham and Mr Jeffress - who called storming the Capitol "a sin against God" - have condemned the violence but not Mr Trump's role in provoking it.

Mr Graham has also speculated without evidence that those who invaded the Capitol building were antifa, though the FBI has said it found no evidence of their involvement.

Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has also made it clear they were not behind the riots.

Among the few Trump supporters to have criticised the president is the Reverend Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville.

In Michigan, President Trump's supporters kneel in prayer in front of the State Capitol

He told the Houston Chronicle that Mr Trump "bears full responsibility for encouraging what amounted to an attempted insurrection".

Of people erecting crucifixes and waving religious banners on display in Washington that day he said "it just adds to the scandal to have God dragged into this equation, as if there's divine sanction for this kind of unconscionable activity".

Mr Mohler is currently running for president of the Southern Baptist Convention - the largest protestant denomination in the US - and will hold significant sway if he wins.

Nevertheless, polling expert Robert P Jones says Mr Biden has "his work cut out" for him when it comes to cooling the temperature and uniting America's political, racial, and religious divides.

"I don't see any movement here," he said of Mr Trump's evangelical supporters.

"Nothing that President Trump has done in the last four years has deterred white evangelical support at all."

- Published2 June 2020

- Published14 January 2021

- Published29 January 2018

- Published16 April 2021