Cancel culture: Have any two words become more weaponised?

- Published

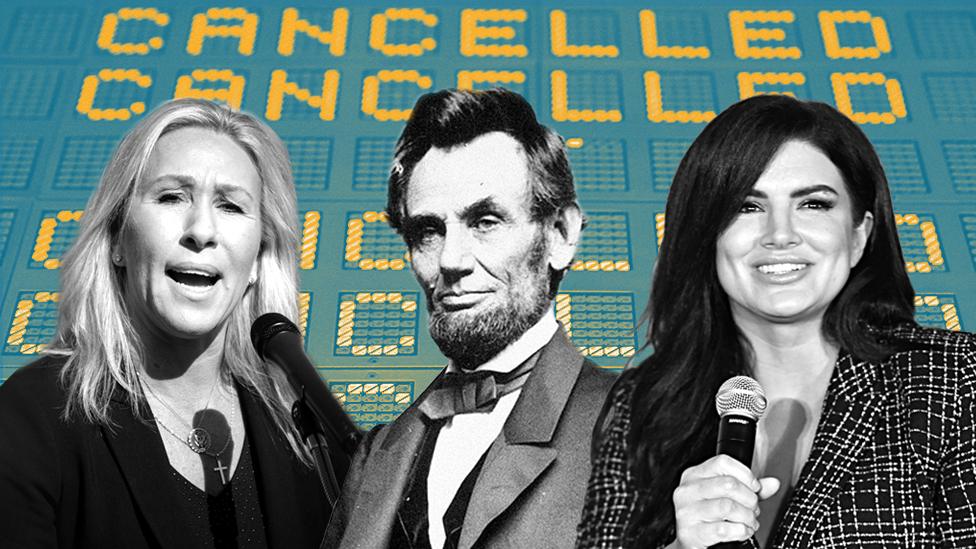

A US president is banned from social media. A long-time national science reporter resigns in disgrace after repeating a racial slur. A school district drops the names of famous Americans from its buildings. A congresswoman is punished for spreading conspiracy theories.

Each one of these episodes has been cited as evidence of "cancel culture" - the idea that zealous activists, mostly on the left, are seeking to suppress disfavoured free expression by permanently shaming and ostracising individuals who have been deemed to have transgressed.

Just last week, Donald Trump's legal team derided his impeachment trial as "constitutional cancel culture". Disney severed ties with actress Gina Carano, who portrays a popular character in its Star Wars series The Mandalorian, reportedly because of inflammatory social media posts on mask-wearing and the US election.

The national media seems to have a steady supply of new sources of righteous outrage for both sides of the cancel culture debate.

The consequences of being "cancelled" include the loss of friends and social connections, the termination of employment or business opportunities, the denial of a platform from which to share their provocative views.

Sometimes the focus of the outrage is a public figure; other times a private citizen whose actions have been captured and disseminated on social media is in the cross-hairs. In either case, the response can be similarly ferocious. "Cancel culture" frequently makes no distinction.

"The term is shambolically applied to incidents both online and off that range from vigilante justice to hostile debate to stalking, intimidation and harassment," writes Ligaya Mishan in the New York Times. , external

"Those who embrace the idea (if not the precise language) of cancelling seek more than pat apologies and retractions, although it's not always clear whether the goal is to right a specific wrong and redress a larger imbalance of power."

Let's take a closer look at those examples.

Donald Trump's Twitter exile

A survey of the landscape has to start at the top, however, with one of the most powerful people in the world being held to task.

On 9 January, just three days after Donald Trump gave a rally speech to supporters who just hours later stormed the US Capitol, social media company Twitter permanently banned his account from the site.

After saying that the move was the "right decision," Twitter chief executive Jack Dorsey acknowledged that it was also potentially chilling to open speech, external.

Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey has defended the decision to ban Donald Trump's account

"Having to take these actions fragment the public conversation," he wrote in a series of tweets. "They divide us. They limit the potential for clarification, redemption and learning. And sets a precedent I feel is dangerous: the power an individual or corporation has over a part of the global public conversation."

The response from Trump's supporters was quick and furious, however. Trump adviser Jason Miller said that "big tech" was trying to cancel the 74 million Americans who voted for Trump in 2020.

If the president of the United States can be cancelled - his backers were saying, both explicitly and implicitly - then what chance do you have of navigating the treacherous waters of modern society?

A New York Times writer's 'intent'

Although some conservatives characterise the "cancel" movement as an attempt by liberal media to damage high-profile Republicans like Trump, its targets aren't always political figures - or conservatives.

New York Times reporter Donald McNeil had been with the paper for 44 years and taken on a particularly prominent role in 2020 as an expert on the catastrophic global spread of Covid-19. Last Saturday, he announced he was resigning because of what he called his "extraordinarily bad judgement".

During a 2019 trip with teenage students to Peru, he said, he had repeated a racial slur as part of a conversation about whether a 12-year-old should have been suspended from school for using the word.

"Originally, I thought the context in which I used this ugly word could be defended," he wrote. "I now realise that it cannot. It is deeply offensive and hurtful."

Times executive editor Dean Baquet had at first only internally disciplined McNeil for the incident.

But after a pressure from parents of the students on the trip - who alleged McNeil made other comments denigrating black teens - and a letter from other Times staffers calling for McNeil's termination, he said he welcomed the resignation and that the paper does not tolerate racist language "regardless of intent".

That prompted author Glenn Greenwald to lash out at what he saw as an "intent is irrelevant" standard, external for off-limits words.

"The overarching rule of liberal media circles and liberal politics is that you are free to accuse anyone who deviates from liberal orthodoxy of any kind of bigotry that casually crosses your mind," he wrote. "Just smear them as a racist, misogynist, homophobe, transphobe, etc without the slightest need for evidence — and it will be regarded as completely acceptable."

As is often the case with headline-grabbing controversies like this, there's often more to the story than first reported. It's not black-and-white, and real humans - with all their complex mix of real faults and virtues - are involved. At some point, the details of the controversy become secondary to the debate that emerges from it.

For Greenwald, for instance, the Times episode is simply a new piece of evidence that there are two sets of standards at play - one for people who make controversial speech and those who make accusations.

Marjorie Taylor Greene's slippery slope

Earlier this year, a member of Congress was the one whose controversial speech came in the form of accusations. Marjorie Taylor Greene stood charged with trafficking in conspiracy theories - about Democrats, about religious minorities and about events like school shootings and forest fires.

Shortly before Democrats and 11 Republicans in the House of Representatives voted to remove Greene from her congressional committee assignments for her past controversial statements, Congressman Jim Jordan took to the airwaves to issue a warning.

"No one is condoning the remarks she has made," Jordan said of Greene's seeming endorsement of violence directed at Democratic leaders and suggestion that high-profile school shootings were staged by anti-gun activists. "That is not the issue. The issue is once this starts, tell me where it ends. Who is next?"

Jordan offered a similar defence during Trump's impeachment vote in January - that the left's attempt to punish conservative politicians for their speech would, inevitably, lead to an environment where average Americans are also at risk.

"The cancel culture doesn't just go after conservatives and Republicans," he said. "It won't just stop there. It'll come for us all. That's what's frightening."

Steve Bennen of MSNBC offers the counterpoint., external

"Is there literally no limit to what a politician can say without consequence?" he asks. "And if the answer is that some limits exist, the question then becomes even more straightforward: why are Jordan and his far-right cohorts convinced that Greene's radicalism didn't go too far?"

At the centre of the debate over "cancel culture" is one of action and consequence. When do words merit punishment? And what form - and permanence - does that punishment take?

Abraham Lincoln High School no more

The push for accountability - or cancelling - isn't limited to recent words or even to people who lived in the past century. In January, the San Francisco Board of Education voted 6-to-1 to rename 44 of its public schools as a way to "dismantle racism and white-supremacy culture", in the words of board president Gabriela Lopez.

Buildings named after historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln, George Washington and Paul Revere, as well as modern ones, like California Senator Diane Feinstein, are designated for rebranding.

In an interview with the New Yorker's Isaac Chotiner, Lopez defended the decisions, external - some of which were based on questionable history - as a matter of community values. She said Lincoln enacted policies that mistreated American Indians, for instance, but there was more to it than that.

"Lincoln isn't going away, but our school district is taking this opportunity to highlight someone else, highlight someone who normally isn't acknowledged but has contributed to the progress of people of colour, or the progress of the community that we're serving in San Francisco," she said.

That hasn't stopped the board's action from generating a firestorm of controversy. San Francisco Mayor London Breed, a Democrat, called the vote ill-timed, given the challenges schools are facing during the coronavirus pandemic

"The possibility that judging past figures by the standards of the present is both untenable and ethically suspect did not, apparently, occur to the committee," he wrote. "Nor did the committee decide that the towering achievements of Lincoln or Washington or Jefferson might just outweigh their shortcomings."

One of the warnings lobbed by those who rail against "cancel culture" is that it will eventually know no boundaries. The living and the dead will all be subject to judgement by the contemporary standards of the day - standards that can change according to political whim.

Free speech and accountability

An open letter from 153 public figures published in Harper's Weekly last July, external, at the height of the Black Lives Matters protests, warned of the "forces of illiberalness" whose "censorious" nature would threaten the free and open discussion of ideas.

"The restriction of debate, whether by a repressive government or an intolerant society, invariably hurts those who lack power and makes everyone less capable of democratic participation," signatories like JK Rowling, Malcolm Gladwell and Noam Chomsky write in the letter. "The way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument, and persuasion, not by trying to silence or wish them away."

Conservatives have been quick to latch onto the term as a political cudgel to use against liberals whenever they face political adversity.

What it's like to be "cancelled"?

"This is the left looking to cancel everyone they don't approve of," said Republican Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri, who cited "cancel culture" as a reason publisher Simon & Schuster terminated his book deal after he supported challenges to Joe Biden's presidential victory. "I will fight this cancel culture with everything I have."

The response from the left, however, has been that there's a difference between cancelling someone and holding them accountable for their actions; that free speech is protected from government interference but its abuse has consequences within society.

Parker Malloy of the liberal watchdog group Media Matters for America says that many of the conservative arguments against "cancel culture" are abandoned when the sides are switched and it is liberal words or actions that are found objectionable. She notes Hawley, for instance, celebrated a push to have credit-card companies stop doing business with adult website Pornhub.

"It's OK to believe that social or professional consequences for things said or done are either too harsh or not harsh enough," she writes, external, "and it's OK to be concerned about the outsized power tech companies like Facebook or Twitter have in the world, but using the framing of 'cancel culture' to make these points will always come off as lazy and cowardly."

Related topics

- Published5 February 2021

- Published4 February 2021

- Published8 October 2020

- Published7 July 2020

- Published9 January 2021

- Published8 July 2020