Netflix and Anna Delvey: The race to secure the story of New York's 'fake heiress'

- Published

Anna Sorokin's trial captured a lot of online attention

It was an elaborate, truth-is-stranger-than-fiction scam that went on for years under the radar, but when word finally got out that a young woman had been conning people in New York by faking it as a millionaire heiress, social media went wild. Now that Anna Sorokin - aka Anna Delvey - has served her time in prison, here is the story of Netflix's race to tell the tale and her life on the other side.

Back at the end of May 2018, 27-year-old Anna Sorokin awoke for another day inside New York City's notoriously rough Rikers Island jail. Having caused financial chaos amid a small circle of people and banks, she was awaiting trial on various theft charges. Until this point, she was largely unknown to the wider world. This was all about to change.

It is not always easy to predict which stories will go viral. Everyone wants the secret formula, but the first exposé of the Anna Sorokin case in The Cut, external was the nearest you could get to having all the right ingredients: money, intrigue and a jaw-on-the-floor scam. According to industry tracker Chartbeat, it is believed to be the sixth most-read story of that year, worldwide.

In case you missed it: this was a story of a recent magazine intern who pretended to be the heir to a fortune and managed to con bankers, hoteliers and new-found friends out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. While on the surface she showed off designer clothes and a jetset life on Instagram, behind the scenes she was bouncing cheques and forging documents to secure loans. She went by the name of Anna Delvey, but, in reality, she was Anna Sorokin, from an average Russian family who lived in Germany. The police finally caught up with her while she was on the run in Malibu, California.

The story, with all its audacious and cinematic twists, instantly captured imaginations.

Less than two weeks after the magazine article came out, prisoner number 19G0366 signed a Netflix contract for film rights to her story.

BBC News has obtained a copy of the contracts between Netflix and Sorokin, through a freedom of information request, as the paperwork was required to be lodged with state authorities after she was convicted.

They show that the first fee of $30,000 (£20,000) was agreed on 8 June. It was the "initial" payment, as her lawyer, Todd Spodek, emphasised. Underneath her signature, two names were typed - "Anna Delvey aka Anna Sorokin" - just to be sure.

Over time, payments from Netflix to Sorokin would rise to $320,000. And for the first time in almost 20 years, they triggered a controversial New York law, designed to stop convicted criminals from profiting from their crime.

Netflix has abided by those US laws; there has been no legal wrongdoing, as we will explain below. But its quick action in securing the deal shows how important viral stories are to streaming services.

The profitable 'summer of scam'

In 2018, Netflix was in the market for big hits. It was churning out content to a massive subscriber base, but it was - and still is - hugely in debt.

The pressure was on to produce original content, especially as other streaming services - from Disney, Apple and HBO - were known to be in the pipeline.

Sorokin's story was appealing, not just because it was an astounding tale, but also because interest was already measurable. Her name had been a trending topic on social media; people had been wearing T-shirts with "fake heiress" slogans; Elle Magazine had offered a tutorial on how to get the "Anna Delvey eyeliner" look., external

It was the dawn of what was becoming known as the "summer of scam" or "grifter season".

This is how The New Yorker later described the media interest in such tales:, external "Grifter season comes irregularly, but it comes often in America, which is built around mythologies of profit and reinvention and spectacular ascent." The magazine cited Sorokin's case - "an instant-classic" - but also referenced Billy MacFarland and his disastrous Fyre Festival, and Elizabeth Holmes and her failed biotech company Theranos.

Online, the public were eagerly consuming the related hot-takes and long reads, while the TV and film companies battled it out to produce the definitive on-screen versions. Bad Blood - the book on Ms Holmes' exploits - had already sparked a fierce bidding war for film rights, and two Fyre Festival documentaries were then in production - one by Netflix, one by a competitor, Hulu.

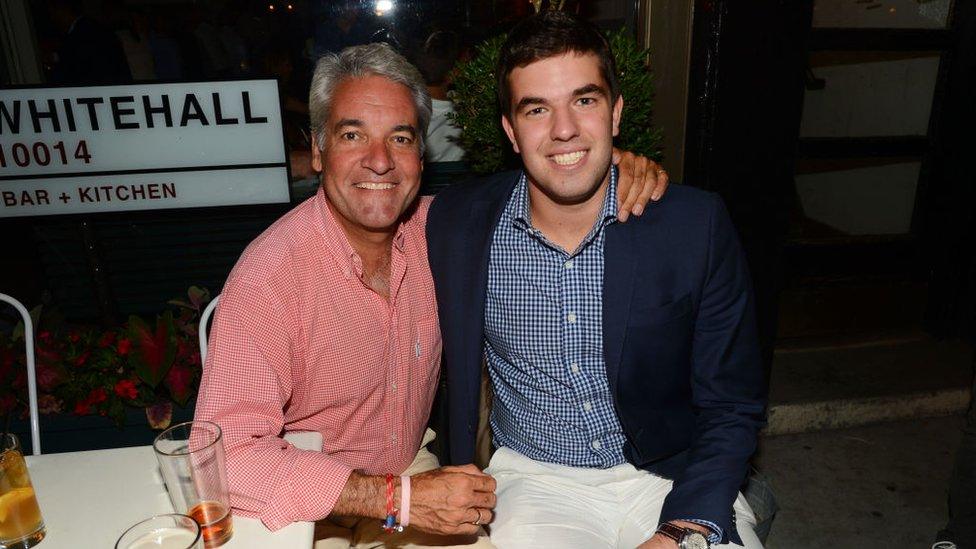

Billy McFarland (right) was convicted of fraud and is serving a six-year sentence

It is not unusual for an entertainment company to leap straight on a story to "option it". This is Hollywood speak for the first step - a relatively small holding fee, while a project's feasibility is considered. This can often lead to limbo for a year or more, and then the whole idea may be scrapped. However, in this particular case, the next move was made without delay. Netflix revealed their big-budget production on 8 June - the same day that Sorokin signed on the line for the first $30,000 payment, and just 11 days after the article about her story was published in The Cut.

Entertainment site Variety announced the production, implying that it may have even happened sooner if it weren't for certain complications: "One insider close to the situation has said the process has been difficult and that Delvey [Sorokin] has been making calls to various talent and producers regarding whom she would like to play her."

By now the story was much bigger than Sorokin herself. At the helm of the series was one of the biggest producers in the US.

Shonda Rhimes - of Grey's Anatomy and Scandal - had signed a three-year deal with Netflix in the middle of 2017 for a jaw-dropping $100m. She and the company had been waiting for the right project to make an impact. A fictionalised drama based on Sorokin's story - later named Inventing Anna - was to be her first production under this deal. The hype was instant.

Shonda Rhimes was an executive producer of Bridgerton but Inventing Anna will be the first show she creates for Netflix

"Expectations are sky high. This is her first time in the writers' room for Netflix," says Lacey Rose of The Hollywood Reporter.

When Rose interviewed Rhimes, external, the producer said she had read the article on The Cut and expressed her interest straight away. Jessica Pressler, the article's author, was quickly contracted, too. Pressler also had a strong track record; one of her previous magazine articles had been turned into the acclaimed Jennifer Lopez movie Hustlers.

"This is the marketplace now," says Rose. "Within hours of articles coming out, you see bidding wars. The space has blown up in recent years and I don't imagine it will slow down any time soon."

Ensuring exclusivity

Netflix's deal with Sorokin later moved beyond the initial optioning deal and, after she was convicted, became a more pricey "life rights" contract. This is common practice in the US, less so in the UK. Among other things, it buys protection from lawsuits, allows you to use someone's image, and can sometimes even include the co-operation of the person as a consultant.

The contract shows Sorokin gave the company exclusive rights and also agreed to potentially co-operate as a consultant. The terms for paid consultancy work include no participation in documentaries or unscripted shows while the series is in production. And no appearances on talk shows or posts on social media about experiences in the series, without the company's permission, for three years after the final episode first airs. She is permitted to write a book, but it cannot be released within a year of the show first airing.

She can, however, speak about experiences outside the show's subject matter. In parenthesis, it says: "So if she cures cancer in the future, we are not saying she can't consult on that."

A "life rights" deal does not mean other people can't tell the story - which has multiple perspectives - but it gives the company free rein and ensures Sorokin cannot assist the competition.

Actress Julia Garner - who has the lead role in Inventing Anna - visited Sorokin in prison

"If you can afford it, it's a smart deal," said one agent, who did not want to be named because they work with Netflix regularly. "It used to happen even more in the day, when you had the big five studios. They were huge buyers of IP [intellectual property rights]. In this case, you are buying exclusivity and authenticity, and you can preemptively shut down the competition."

There have been multiple reports of a competing HBO project, led by screenwriter Lena Dunham (who wrote and starred in Girls) and positioning Sorokin's friend Rachel Deloache Williams as the central protagonist. There has also been speculation that this may either have been shelved or that it may go head-to-head with the Netflix version. "Two duelling Anna Delvey series are poised to be the next Fyre Festival doc battle," read a headline on entertainment site The Decider.

HBO told the BBC that project is still in the development stage. There is, however, a separate documentary in the works.

How to do a rights deal with a prisoner

When Netflix first got in contact with Sorokin, she had not been convicted, but once she was, there were rules that needed to be followed. New York's "Son of Sam" law kicked into play.

The law's origins stem back to 1970s serial killer David Berkowitz, known by his pen-name "Son of Sam", amid concerns that he would profit from his notoriety by selling his story. In response, New York state passed a law to prevent profiting from such fame, and multiple states followed suit.

However, publishers fought back.

In the late 1980s, Simon & Schuster was working on a book in collaboration with ex-mobster Henry Hill, when the authorities came knocking over a $90,000 payment. The resulting dispute went as high as the Supreme Court, which ultimately struck the law down, saying it was in conflict with the right to free speech. The book, Wiseguy, went ahead, as did the royalty payments, and it inspired the Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas, from which Hill reportedly earnt a further $480,000.

A reworked Son of Sam law was introduced in 2001. Today, a company is required to notify the Office of Victims Services (OVS) if they are paying a convicted felon more than $10,000. The office will not seize that money, but it will freeze the bank account and notify the victims of the crime, who then can file their own lawsuits to make claims.

Laverne Cox plays Anna's personal trainer, Kacy Duke, in the Netflix production, which has been delayed by the pandemic

This is what happened in Sorokin's case; the banks that she had conned stepped forward.

"OVS was notified by Netflix that it paid Ms Sorokin $320,000 and those funds were frozen," a OVS spokesperson, Janine Kava, told the BBC. "City National Bank filed a suit and obtained $100,000 and CitiBank did the same, obtaining $70,000. The balance of the funds must pay her attorneys' fees; any funds remaining would go to Ms Sorokin."

Signature Bank - which Sorokin also defrauded with a cheque-bouncing ruse - declined to file action.

And Sorokin's friend, Rachel Deloache Williams, was not eligible, because Sorokin was found not guilty on the related charge in court. Williams had infamously footed a $62,000 bill after Sorokin invited her to what she thought was an all-expenses-paid trip to a luxury resort in Morocco. Her money was eventually refunded by American Express and she wrote a book about the experience, My Friend Anna.

According to the OVS, some of the other victims have been paid back in conjunction with other orders from the judge in Sorokin's case.

Paris-based creative director Marc Kremers says he is still owed £16,800 for creating promotional material for the Anna Delvey Foundation - an arts project she was trying to fund via a $100m loan. He was not a direct part in the prosecution's case, so he will not be on the victims' list, but he says he is pursuing the matter separately.

Anna in court with her lawyer, Todd Spodek

The OVS says the Sorokin case was the first test of Son of Sam law since it was reintroduced in 2001.

What is particularly interesting is that Netflix became involved in a pre-trial stage.

"In the UK, making payments to anyone pre-trial is quite problematic," says David Banks, a UK media law expert. Regulations say no payments, or promises of payments, can be made while proceedings are active.

"It would be hard to justify this kind of arrangement in the UK, but in the US it is very different. Look at OJ Simpson. Everyone became a celebrity in that trial, jurors wrote books," Mr Banks says.

Indeed, the Sorokin trial became quite a spectacle. Netflix researchers sat alongside the press, and the defendant employed a stylist, via her lawyer. "Anna's style was a driving force in her business, and life, and it is a part of who she is. I want the jury to see that side of her and enlisted a stylist to assist in slecting [sic] the appropriate outfits for trial," her lawyer, Todd Spodek, told The Cut at the time, external.

Judge Diane Kiesel also acknowledged her celebrity-like status and the buzz around the TV series. "This sentence should be a message to the defendant and any of her fans out there," she said to the courtroom.

Netflix declined to talk to the BBC about whether their payments may have affected the justice process.

The OVS has clarified that Netflix came to them initially, it did not need to chase them, and all US rules were followed. The initial $30,000 was paid pre-trial without objection from authorities. The company also followed the New York court's orders and later payments were all directed to an OVS-monitored account, enabling distribution to victims.

What next for Anna and Netflix?

The pandemic delayed the filming of Inventing Anna last year and the series is now set to be released by the end of 2021.

Anna Chlumsky (centre) is playing the role of the investigative journalist, while Alexis Floyd (right) will be hotel concierge Neff Davis

Netflix's big spends across the board have kept it at the top.

"But one thing that's changed [since the Sorokin deal and since the pandemic] is that platforms can now create their own viral stories," says Tom Harrington, a media analyst at Enders Analysis. "With so many people watching, they can take a piece of programming, put it at the top of their platform, and make it a hit. Look at Tiger King, that guy had talked to loads of people before, but Netflix made it international, so everyone was talking about it at the same time."

That said, the gold rush for "hot ticket" stories remains. Earlier this year, Netflix became one of many players looking to adapt the GameStop saga - a David-versus-Goliath tale of bedroom stocks. There are currently seven projects in their initial stages, external.

As for Sorokin, she was released from prison last week, having served three and half years of a four-to-12-year sentence.

Her lawyer, Todd Spodek, says: "Anna is currently working on her appeal. I anticipate that ultimately there will be deportation proceedings commenced based on her status."

In the meantime, she is back roaming around New York, documenting life on Twitter and Instagram, with her friend Neff Davis (the former concierge at the 11 Howard Hotel where Sorokin ran up a $31,000 bill).

Sorokin posted this photograph on Instagram of her preparing for a magazine shoot this week

Sorokin has also published some prison diary extracts online and is writing a memoir. Her lawyer confirmed that her Netflix contract does bring certain constraints.

Sorokin declined to be interviewed for this story. "Please talk to the global president of Anna Delvey TV," she said in an email.

This turns out to be Doug Higginbotham, an Emmy-Award-winning filmmaker. He is a freelancer and says he does not condone her crimes. Sorokin contacted him last week, saying a TV crew were being too intrusive in following her around. "She thought: why don't I just hire a crew myself, so I can control the narrative?" he says.

He has since been documenting her life, as she deals with the paparazzi, goes shopping and visits her parole officer. "We don't know what we'll do with the footage yet, but she's getting a lot of major offers, so we didn't want to miss anything," he says.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Related topics

- Published26 April 2019

- Published11 May 2019

- Published19 January 2021

- Published31 January 2021